Boston's Back Bay Michae l 4la

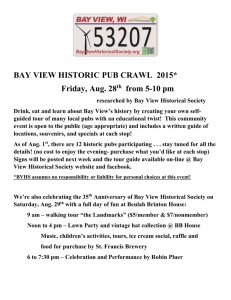

advertisement