REGIONAL LABORATORY EDUCATIONAL

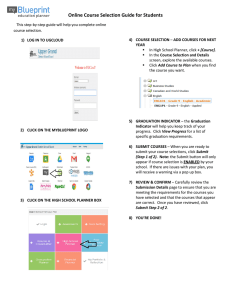

advertisement