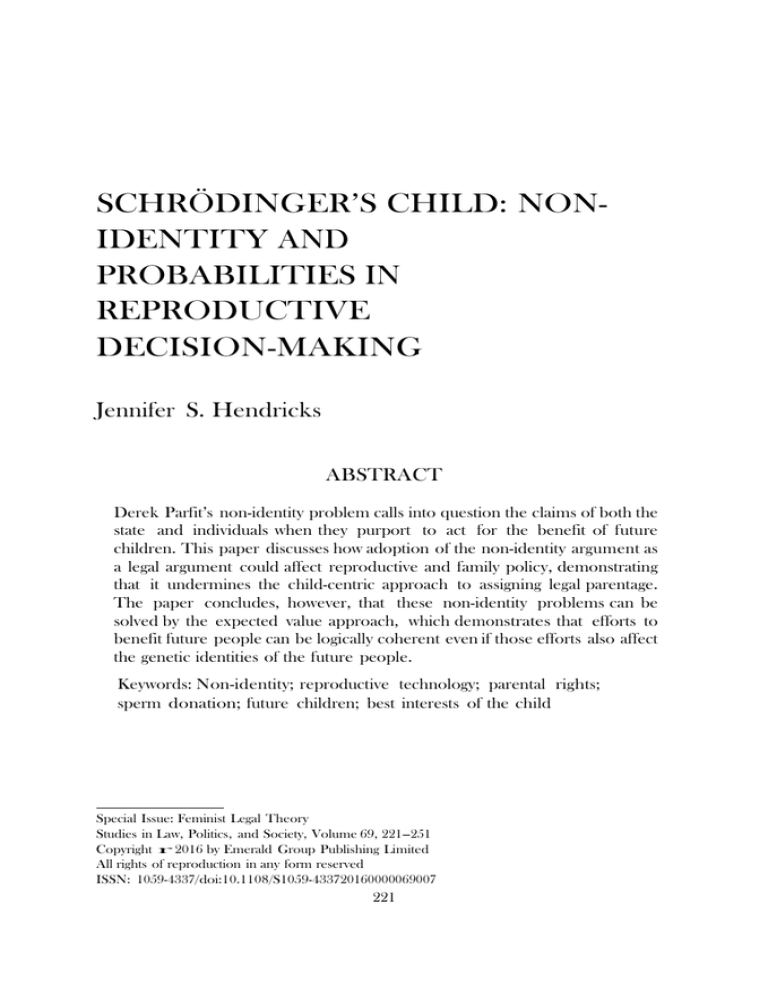

SCHRÖDINGER’S CHILD: NON- IDENTITY AND PROBABILITIES IN REPRODUCTIVE

advertisement