6 avian communities, and landscape David M.

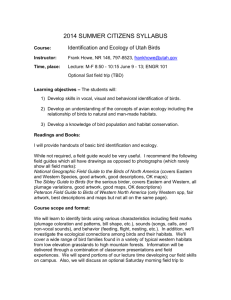

advertisement

6 avian communities, and landscape Miller', JenniferM. Fraterrigol,N. ThompsonHobbs23, David M. . WiensI Colorado State University, 317 WestProspect.Fort Collins. CO 80523 USA ColoradoState University,Fort Collins. CO 80523 USA Birds, Colorado, gradient, landscape ecology, policy, study design, urbanization Humansettlementis a prevalentsourceof land-usechangeworldwide, but our understandingof the effects of settlementon avian communities is limited. Settlement has been characterizedas a gradient that extends from urban developmentto exurban and rural areas. An important advantageof the gradientapproachis the potentialto identify thresholdsin the responseof birds to settlement. Although gradientshave been used in studying the effects of urbanizationon birds, relatively little attention has beenpaid to the exurban end of the spectrum,despitethe potential for this type of developmentto affect large expansesof habitat. Studies at relatively fine scales are useful for investigatingthe influence of proximate factors, such as vegetationstructure and composition,on birds in human-dominatedareas. However,such studies must be coupledwith investigationsat broaderscalesto gain a more complete understandingof the ways that human settlementaffects bird communities. Urban-wildlandgradientscan be quantified using remotely-sensedimagery in combination with data on the intensity and pattern of settlement. However, metricsusedto describepatternsof settlementareonly usefulto the extentthat they representsomethingmeaningful to birds. The extent of the landscape mosaic surroundinga study site that needsto be quantified dependson the 18 Chapter6 goals for a particular study. We proposea researchprotocol for studyingthe effectsof settlementon birds that may be usefulat multiple scales. Study sites are distributedamong land-coverand settlementtypes, and replicatedsurveys are progressivelyaggregatedfrom small to large scales. Thesedata serveas the basis for interpolation, using traditional statistical tools and geostatistical methods,to areasnot sampled. To be effective,conservationmust be focused on landscapemosaics,not habitat patches. Areaswherepeople live and work are importantcomponentsof thesemosaics. 1. INTRODUCTION Development associated with human settlement has emerged as a prevailing source of land-usechange throughout the world (Berry 1990; United Nations Centrefor Human Settlements1996;Cohen 1997;Marzluff 2001). In the U.S.A. alone,nearly 6 million ha of forest and rangelandwere convertedto housing and various settlement-relatedinfrastructurebetween 1982and 1992(NRCS 1995). Such developmentis not evenly distributed geographically, nor is it limited to urban areas. Extensive landscape transformationin the Rocky Mountain region, for example,is the result of a populationgrowth ratethat is threetimes the nationalaverage.Coloradois a bellwether of change for this region, with 6 of the 10 fastest-growing countiesin the nation (including the top three)- all exceeding6% population increasesper year between 1990 and 1998 (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1998). Although much of this growth is manifest in typical urban and suburbansprawl, the conversionof agricultural and forested land to lowdensity residentialdevelopmentis occurring at unprecedentedrates(Knight et al. 1995,Riebsameet al. 1996). Urbanization clearly harms some native bird species(Marzluff 2001). Our understandingof the mechanismsunderlying such effects has been explored by Bolger (2001) and Marzluff (2001), but remainsrudimentary, largely becausemany ecologistshaveavoidedhuman-dominatedsystemsas locationsfor study. In the relatively few studiesthat havefocusedon settled areas, researchers have usually concentrated on urban or suburban environmentswhile areasof lower residentialdensity have generally been ignored. Furthermore,most studieshave been conductedat relatively fine scales(but also seeBlair 1996,Nilon et al. 1995,Clergeauet al. 1998). For thesereasons,the scientific basisfor avian conservationin developedareas remains weak, particularly in areas of lower settlementdensities and at landscapeand regionalscales. Our goal is to contribute to the dialogue on the direction of future researchon bird communities in human-dominatedareas. We begin by examining gradientsof human settlementwith specialattentionto portions of such gradients that have thus far received scant attention by avian 119 Next, we consider issues of spatial scale and stress the of a multi-scale approach to examining the effects of Finally, we discussresearchneedsas well as several in designing and implementingeffective policies for GRADIENTS OF HUMAN SETTLEMENT have treated "urban" as a separatetype of land-cover, , or "grassland." This is similar to the way that . . in land-usedatabasessuchas ..~_.-" (Anderson et al. 1976), where the only is betweenurban and non-urbanareas.However,the true extent . may be vastly underestimatedby such conceptualizations "urban" is an endpointon a continuumof settlementintensity- a that extends from sparsely populated rural areas to large cities 2001). When we comparedenselypopulatedurban areasto , -- - --- -- - -- ." ~, . shrubs. Suburban areas often give way to exurban residential - - ~ Ultimately, exurbandevelopmentgradesto rural areas, Settlement is not a matter paradigm" has long been used in 1967) at a variety 1981). and ---~ function of of spatial The ecological ecology and scales underlying systems as a basis has been (T erborgh assumption vary in for applied to 1 971 , is that space, and this variationcan enhanceour knowledgeof system-level McDonnell and Pickett . gradient" a "powerful organizing (1990) and tool" have described suggested for that ecological urbanization the gradient research as a paradigm in human- .-. . gradients are indeed complex. In major metropolitan areas, extending from the urban core reveal an interspersionof dense development, parks, lower-density suburbs, and smaller city . A designbasedon linear transectsis usefulfor 120 Chapter6 A. ¥ ~ ~ . . &--+ ~ Residential urban L--1-'i - ;8 B, Figure 6.J. Humansettlementalong the northernFront Rangeof Colorado(both panels:Fort Collins-top, Loveland-bottom,and Greeley-right). (A) Areasclassifiedasresidentialurban land-coverfrom the USGS 1:250,000LU/LC map series. (B) The full gradientof housing densitiesfrom urbanto rural using U.S. CensusBureaublock-level data 121 - ' of development (seeSavardandFalls2001),but as (2001) note, urban-ruralgradientsare not purely geographical. -. .'to examiningthe effectsof settlementon birds doesnot study sites to be aligned in this fashion and other ways of . . may be more informative. One might comparesites of different types or intensitiesof development(Blair 2001; Ctergeau et at. 1998), or examine the effect of varying . habitattype (Friesenet at. 1995, -. 2001). importantadvantageof the gradient approach,as opposedto binary . ,(e.g., urban vs. rural or suburbanvs. wildland), lies in its --- for identifying thresholds or breakpointswhere human impacts markedchangesin biotic responses(Wiens 1989). Such thresholds be found, for example, in measuresof human density, patterns of or distance from developed areas (Bolger et al. 1997). are important simply becausethey offer a clearer basis for such as the determinationof buffer distancesfor sensitive species . . . recentlysurveyed41 peer-reviewedstudiesof avian communitiesin -- humansettlementthat were publishedbetween1970and 1999. Of investigations,12 utilized a gradient-basedresearchdesign. In most the gradientswere restricted in the levels of developmentthat were only five studiescoveredthe spectrumfrom urban or suburbanto In fact, the low-density portion of the gradient has not much attention generally (only four of the 41 studies included sites) despite the increasing pervasivenessof this type of 2.1 Exurban Development In Colorado,exurbandevelopmentexpandedat a paceof 8.3% annually between1960 and 1990 - nearly three times the rate of population growth (Theobald2000). This type of low-density developmentis expectedto continuein Colorado and elsewhere,fueled by the growth of recreation-, service-,and information-basedindustries; dissatisfactionstemming from various problems associatedwith urban and suburban living; aesthetic considerations; and recreationalopportunities. Locationsnear federal lands suchas National Parks and National Forests - places often viewed as conservation areas- appearto be particularly attractive(Nelson 1992,Howe etal. 1997,Marzluff et al. 1998). Although individual buildings are more widely spaced in exurban developments, this does not necessarilymeanthat the effects of settlement 122 Chapter6 are restricted to a small portion of the landscape. As rural areas are converted to exurban residential development,road density is likely to increase. Existing roads will experiencegreater traffic becausewidely disperseddevelopmentmeansmore vehicles per householdand more trips per day per vehicle (Romme 1997). Roadsare associatedwith an effect zone - an areaof ecological impact on either side of the road itself - that extendsoutward from tensto hundreds of meters (Forman and Alexander 1998). Numerousspeciesof grassland birds and forest birds have beenfound to avoid roads(Ferris 1979,van der Zande et al. 1980). Researchin the Netherlandsshowed that the effectdistances(the distance from a road at which population decreaseswere detected)varied with traffic density and habitat; 60% of the bird species presentoccurredat lower densitiesnear roads,and songbirddeclineswere coincidentwith thresholdsin traffic noise(Reijnen et al. 1995,Reijnenet al. 1996). Moreover, evidencesuggeststhat mammalianpredatorstravel along low-traffic roads (Bennett 1991, Forman 1995) and increasedrates of nest predation have been found near low-traffic road edges(Small and Hunter 1988). Roads may turn source habitats into sinks by increasingmortality rates (Mumme et al. 2000) and roads may also alter avian community composition by attracting edge species,particularly in forested habitats (HanowskiandNiemi 1995). One can imagine that buildings also are associatedwith an effect zone, although this phenomenon has not received as much attention from ecologists. A building-effect zone with reference to birds might be a function of humanactivity, noise, or free-rangingpets. Although the effect of anyone building on the surrounding matrix is probably small, the cumulative effect of many buildings may be substantial(Theobald et al. 1997). Building effects might cause avoidancein some species(O'Dell 2000), whereasspeciesthat are tolerant of human presencemay benefit. Given the rapid increaseand dispersednatureof exurbandevelopment,this little-studiedportion of the gradientof humansettlementhasthe potentialto alter the structureof bird communitiesover largeareasin someregions. 3. SPATIAL SCALE 3.1 Local Scales Traditionally, ecologistshave focused on within-habitat diversity when conductingresearchon bird communitiesand have ascribeddifferencesin avian diversity to variation in habitat features such as foliage-height diversity or horizontal habitat heterogeneity(MacArthur and MacArthur 6. Urban bird ecology 123 1961,Karr and Roth 1971, Willson 1974). In an effort to reduce spatial variationand thereby allow "fair" comparisons,sampleshave usually been collectedover small plots or quadrats,usually < 0.5 km2,locatedin a single habitattype. Studydesignsbasedon within-habitat diversity also have beencommon in researchon urban birds. Severalworkers have examinedrelationships betweenavian community composition and attributes of urban woodlots (Tilghman 1987) or parks (Gavareski 1976, Cicero 1989) including vegetation,patch area, or the presence of human artifacts such as recreationaltrails. Similarly, DeGraaf and Wentworth (1986) described suburbanbird assemblagesin Amherst, Massachussetts,and attributed differencesin avian community structure to various aspectsof the built environment,particularly those relating to vegetation(see also Savardand Falls2001). Nest loss in developedareasalso has been examinedrelative to local habitatfeatures (Haskell et al. 2001). For example, Major et al. (1996) found that nest predation increasedwith nest height and tree density in residentialbackyardslocated in Australian urban areas. Miller and Hobbs (2000) examined nest predation in lowland riparian areas adjacent to suburbandevelopmentalong the Front Rangeof Coloradoas a function of distancefrom recreationaltrails. Mammaliannestpredatorstendedto avoid trails, whereas avian predatorstended to prey more on nests near trails (Miller and Hobbs 2000), similar to the effects of buildings and human activityon nestingbirds reportedby OsborneandOsborne(1980). Studiesat local scaleshave advancedour understandingof proximate factorsthat affect bird distributions in areasof humansettlement,but many questionsremain to be investigated. Vegetationstructureand floristics, for example,have been frequently cited as important determinantsof habitat suitability for some species(Beissinger and Osborne 1982, Green et al. 1989,Jokimaki and Suhonen 1993, Rolando et al. 1997, Germaineet al. 1998). However, an exclusive focus on the fine-scaleattributesof humandominatedareasreflects the belief that local featuresare synonymouswith "habitat." Evidence suggeststhat additional factors operating at broader scalesalso influenceavian communitystructure. 3.2 LandscapeContext Landscapecontext may influenceecologicalprocessessuchas thosethat detenninelocal avian diversity becausebirds are highly mobile organisms and likely respond to habitat features across a range of spatial scales (Hostetler 200I). Hilden (1965) suggestedthat habitat selection by migratorybirds could best be viewed as a hierarchicaldecisionprocessthat 124 Chapter6 starts at regional and landscape scales and proceeds to fine-scale habitat characteristics. If this is true, then we might sometimes expect similar habitats to support different bird assemblages, depending on the structure and composition of the surrounding landscape matrix. Pearson (1993) found that much of the variation in the abundance and diversity of wintering birds could be explained solely by landscape variables. Several workers have reported a positive relationship between the width of a riparian area and avian diversity (Stauffer and Best 1980, Darveau et al. 1995, Hodges and Krementz 1996), but this relationship does not always hold when wider riparian areas are surrounded by urban or suburban development (Miller et al. 2001). Many mechanisms may mediate the effects of landscape context on avian communities in a given habitat type. Birds nesting in forest fragments may be subjected to different nest predators and experience different rates of nest predation depending on the nature of the areas surrounding these patches (Andren 1992, Marzluff and Restani 1999). Szaro and JakIe (1985) found that birds associated with riparian habitats comprised nearly a third of avian assemblages found in desert scrub but that this percentage decreased with distance from the riparian zone. Clearly, conclusions drawn on the sole basis of local habitat features without consideration of landscape context may be misleading. When assessing the effects of landscape context, ecologists often have focused on landscapeswhere the primary anthropogenic impacts involve the conversion of land-cover types such as forest and woodland to clearcuts and cropland, commonly thought of as habitat fragmentation (Harris 1988, Saunders et al. 1993, Schwartz 1997). Indeed, contemporary thinking about anthropogenic impacts on landscapes is dominated by the fragmentation paradigm, by the idea that the integrity of many ecosystems is diminished by human activities that isolate well-defined habitat patches in an ecologically compromised matrix. Although this paradigm may apply well to landscapes in which the primary effects of human land-use involve the wholesale conversion of land-cover types, including native habitat remnants embedded in high-density urban areas (e.g., Central Park in New York City), it is not especially faithful to the effects of settlement at lower densities. In their study of the Golden-cheeked Warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia), Engels and Sexton (1994) noted that it is often difficult to delineate patches in urban and suburban areas in a meaningful way because the effects on birds of the defining features of built environments, such as streets and buildings, are poorly understood. Engels and Sexton (1994: p. 287) observed that the woodlands in the vicinity of Austin, Texas ".. .are more frequently speckled by urban structures than isolated by them into discrete islands." Generalizing this idea, we suggest that in many instances the ~ 125 human settlement ml!Y be better represented as . used by ecologists when images -- -~--~ canopy or :.. cover, but aerial forested quite studying photos, areas. "perforations" fragmentation may fail Two different sites with ~ at to capture may respect the be similar to of Furthermore, the data broad scales, true extent in intensity terms of of of , frequentlyusedby urbanplannersandgeographers, are measuring boththeintensityandpatternof settlement (Alberti , --' 2001). Parcel maps, for example,may be acquiredfrom county tax offices and provide spatially-explicit information on building building age, and zoning restrictions for a given parcel. Such in combinationwith remotely-senseddata, provide the meansfor gradientsof human settlement. This being said, it should be : ability to computean ever-expandingarray of landscape Intact Fragmentation Perforation Figure6.2. Contrastinglandscapepatternsassociatedwith habitatfragmentationandhabitat perforation.Black areasin the lower panelsrepresenthabitatremoval. Fragmentationresults in the large-scaleconversionof land-covertypes(by timber harvestor agriculture,for example)and discretehabitatpatchessurroundedby a highly-alteredmatrix, whereashabitat perforationresultsin a landscapespeckledwith disturbancepoints (suchas individual houses or clustereddevelopments). 126 Chapter6 metrics for the purpose of describing settlementpatterns far exceedsour ability to relatethesemetricsto ecologicalprocessesin a meaningfulfashion (Gustafson1998,Turner et al. 2000). Once the metrics are computed,the more-difficult task of determiningthe extentto which they representpatterns that are importantto birds still remainsto be done. How much of the surroundinglandscapematrix should be quantified? This is a vexing questionthat only recently has begun to be addressedby ecologists. The answer likely depends on a suite of factors, but two important considerationsare the ecological traits of the species under investigation and the portion of the urban-rural gradient that is being examined. Different species may respond to the landscapeat different scales,dependingon traits such as body size and trophic status(Hostetler 2001). Thus, a study of the effects of settlementon habitat use by raptors may require measurements over a much broaderareathan a similar study on songbirds. The type of developmentthat occurs in the surroundinglandscapealso may dictate the scale of study. The pattern or intensity of development within, say, 100 m of an urban study site may be quite different than that occurring within 500 or 1000 m. Becauseexurban developmentis, by definition, more diffuse, spatial patterns usually change more gradually comparedto urban areas. One way in which investigatorshave tried to assessthe scale at which birds are respondingto their environment is by determining the amount of variation in avian community structure (e.g., richness, density, composition, species presence/absence) explained by landscapemeasuresbeyond that accountedfor by local habitat features (Pearson1993,Knick and Rotenberry1996,Bolger et al. 1997,Saab1999). As a final point, we note that most researchon human settlementhas been conducted in forested landscapes(Marzluff et al. 2001). In this context, it is not surprisingthat ecologistshave assertedthat urbanizationis synonymous with the simplification of habitat structure compared to undevelopedareasand leads to overall reductionsin avian diversity (Geis 1974,Aldrich and Coffin 1980,Beissingerand Osborne1982,DeGraafand Wentworth 1986). However,developmentalsocan result in a more complex habitat structure compared to the presettlement landscape. Human settlement in the arid and semi-arid regions of North America often is accompaniedby the planting of trees,shrubs,and expansivelawns as people try to recreatethe familiar landscapesfrom which they came (Limerick 1987). As a result, habitat structure becomes more complex and the diversity of birds associatedwith the built environmentin theseareasis, in some cases,greater than that of the predevelopmentlandscape(Guthrie 1974, Vale and Vale 1976, Sodhi 1992). The same may be said of development in areas formerly dedicated to intensive agriculture, as 6. Urban bird ecology 127 monoculturesare replaced with more diverse habitats. Again, landscape contextmatters. 3.3 Regional Perspectives Most investigationsof the effects of urbanizationon bird communities havebeensomewhatrestrictedin terms of spatial extent. In our review of aviancommunity studies in areasof human settlement,the majority were conductedin a single city or town (n = 32). Five studiescomparedbird communitiesacrossmore than one city, but only a handful were extendedto include the matrix in which the cities were embedded. Three studies examinedeffects at a county-wide scale and only two consideredeffects acrossmore than one county. As a result, the cumulative effects of settlementat regional scalesare virtually unknown. A regional perspectiveis important, both in assessingthe cumulative effects of settlement and in managing human population growth. For example,Marzluff(2001) notedthat growth control in Portland,Oregon,has simply transferred development pressure to outlying communities. Furthermore,just as landscapesare perforatedby individual buildings and smallresidentialclusters,regionsare perforatedby cities, towns, and larger suburbanenclaves surrounded by exurban development and linked by transportationnetworks. Thus, a regional perspective is a necessary componentof comprehensiveavian conservationstrategiesif they are to be effective(Knopf and Samson1994). 4. A MULTI-SCALE RESEARCH PROTOCOL Becausewe will never be able to measureprocessesand statesfor more thana tiny fraction of a region, we need samplingdesignsthat allow us to extrapolateto unmeasuredareas. We therefore propose a multi-scale researchprotocol for assessingthe effects of development on avian communities(Fig. 6.3). This protocol could be usedto comparethe effect of differentpatternsor densitiesof settlementon birds within a city, between sitesat different points on the urban-ruralgradient,or acrossa region. Data obtainedwith this method also could be integratedwith spatially-explicit modelsof land-usechange,basedon demographicand economic drivers (Theobald and Hobbs 1998), to identify important habitats that are particularlyvulnerableto future residentialdevelopment. Traditionalavian censustechniques(point or line transects,circular plots) in combinationwith fine-scale habitat measurements(vegetationstructure andfloristics) arethe foundationof this method. Setsof local surveysare 128 Chapter6 ~ Selectpatchesof eachland type in the study areausing a stratified-randomprocedure ~ Randomlyselectsurveypoints within replicatepatchesof eachland type ~ Randomlyselectsmall plots in the vicinity of eachsurveypoint Field data Bird surveys Small-plot measurements Large-plot measurements ~ Test model predictions with new field data ~ Developspatialmodel integratingfield data,remotesensingimagery,and measuresof humansettlement ~ Interpolateto areasnot sampled Land-useplanning Figure 6.J. Multi-scale researchprotocol for assessing the effectsof developmenton bird communitie~ 6. Urban bird ecology 129 distributed across the spectrum of land types in the study area using a geographic information system (GIS) and a stratified random design (Fig. 6.3; step 1). For our purposes, land types are defined by measures of human settlement intensity (road density, building density, etc.) superimposed on habitat types (forest, grassland, etc.) to represent the full gradient of settlement occurring in the focal area. Undeveloped sites also could be included. Bird survey points are placed within patches of each land type (step2) and smaller plots are placed in the vicinity of each point (step 3); the exact locations of points and plots are determined using a stratified-random procedure. Appropriate habitat measurements (canopy cover, shrub cover, etc.) are taken over the larger plots, or the area over which birds are counted at each point, and fine-scale habitat measurements (leaf litter, coarse woody debris, etc.) are taken in the smaller plots. The sampling design is hierarchically nested so that replicated surveys and habitat measures can be progressivelyaggregated at broader scales. A spatial model is then developed that can be used to correlate broadscaledata derived from satellite imagery or aerial photography and measures of settlement pattern or intensity with fine-scale data on bird communities and habitat structure (step 4). To examine spatial dependence among variables, one might use traditional statistical methods such as stepwise regression in combination with geostatistical tools such as trend-surface analysis(Gittens 1968). It then becomes possible to interpolate to areas not sampled (Robertson 1987; step 5). Land-use planning often involves the application of data-based models to unsampled areas and this is preferable to planning in the absence of field data. Optimally though, a model's performancewould first be assessedby testing its predictions in a new set of studysites (step 6). In addition to their use in applied research, these methods can be used to addressbasic ecological questions. For example, beta diversity is generally thought to increase with an increasing number of habitat types. A recent study conducted in the Colorado Front Range of the Rocky Mountains explored the extent to which this relationship is altered by the effect of human settlement (Fraterrigo 2000). The overall study area encompassed two counties and was dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), aspen (Populus tremuloides), and alpine meadows. The research focused on severalsmall towns that lie along a north-south axis. The basic premise was that if areas of human settlement tend to be more similar to one another in terms of habitat structure than they are to the pre-development landscape (Schneider 1996), their respective bird communities should exhibit greater similarity to one another than to avian assemblages in the surrounding matrix. There is evidence to support this assertion in larger developments at 130 Chapter6 lower elevationsin other regions (Aldrich and Coffin 1980,Beissingerand Osborne1982,DeGraafand Wentworth 1986),but herethe emphasiswas on smallersettlementsor exurbanareasin westernconiferousforests. 5. RESEARCHNEEDS There is a pressingneedfor more researchon virtually all aspectsof the relationshipbetweenurbanizationand bird communities. This appliesto all points along the urban-wildland gradient and across scalesfrom local to regional. Of course,no single study can addressmore than a few aspectsof settlement's effects on birds. Particularly at broader scales, logistical constraintsmake it difficult to include a sufficient number of study sites to teaseapartmore than a few "treatment"effects,evenif we relax assumptions about strict replication (Hargrove and Pickering 1992). Therefore, researchersmust consider the objectives of a project carefully and realistically. This being said, we offer somethoughtson areasof research wherethe needfor additional study is particularlyacute. Our emphasisin this paper on researchconductedover relatively broad scalesshouldnot be construedto meanthat investigationsat local scalesare unnecessary. An understandingof the interaction betweendevelopment, local habitat features, and bird communities is fundamental to accurate interpretation of patterns discerned over landscapesand regions. Data collectedat smallerscalesalso are useful in providing guidelinesfor habitat enhancementto individual property owners, neighborhoodorganizations, and municipal governmentagencies.For example,an urgentneedexists for information on the proximateeffects of streetsand vehiculartraffic, various sorts of humanactivity, and different patternsof tree and shrubplanting on birds. The relative value of native versus exotic vegetationalso requires further examination, particularly the insect loads that different species support (Beissingerand Osborne 1982) and their effect on nest predation rates(Schmidtand Whelan 1999). We believe that investigationsaimed at determiningthe effect zone or "footprint" of individual housesor clustersof buildings shouldbe affordeda high priority by ecologists. Such data are useful in an urban or suburban context, but they are critical in assessing the impacts of exurban development.As we have noted,very little researchhas beenconductedon this part of the urban-wildlandgradient,althoughthis type of development potentially affects vast expansesof habitat. When examiningthe effects of featuresof the built environmentat local scales,it is important that some considerationbe given to the natureof the surroundinglandscape. 6. Urban bird ecology 131 At larger scales, we urge workers to addressthe entire gradient of development,from urban to wildland, in their study designs. There are logisticalchallengesinherentin suchan approachand it is almost inevitable that a tensionwill exist betweencollecting an adequateamount of data at localscalesand visiting a sufficient numberof sitesat different points along thegradient. Nevertheless,suchstudiesare necessaryto placesmaller-scale effortsin a broadercontext and to make fair comparisonsamong different intensitiesof settlementon the gradient. Until there is a greaterbalancein the spatial scales that researchersaddresswhen conducting research,a comprehensiveunderstanding of the effects of development on bird communitiesis unlikely to emerge. 6. POLICY AND MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS Over the last few decades, scientists have become increasingly interested in the role that their research might play in the environmental policy process. Here,our goal is not to provide an exhaustive treatment of the intricacies of policy development regarding natural resource management - this has been done elsewhere (e.g., Ostrom 1991, Lee 1993). Rather, we wish to share a few observations that stem from our attempts (particularly by authors NTH and DMT) to provide scientific support for land-use decisions that affect humansettlement (Theobald et al. 2000). Historically, ecologists and conservation biologists have exerted their greatestimpact on environmental protection by influencing decisions at the national level. The Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered SpeciesAct all are examples of policies that extend "top-down" from the federal government to influence local actions. However, most decisions regarding residential and commercial development are made at the base of the government hierarchy by county governments, municipalities, and landowners(Heatley 1994). This creates several challenges for implementing conservation policy. The first challenge is created by the diffuse nature of land-use decisions. Many seemingly small decisions - choices made at many different times and locations - accumulate to cause large-scale impacts. The fact that these choicesare diffuse in time and space means that it is difficult for experts to inform them. It follows that many local decisions are made without the benefit of scientific input regarding their ecological impacts. Second, the fact that many local jurisdictions, including individual landowners, are responsible for land-use decisions implies that conservation policy at the regional scale must include input from numerous sources. Achieving consensus or even agreement among these many jurisdictions may be 132 Chapter6 impossible, and when consensus is reached it might be forged from compromises that fail to deal with fundamental conservation issues. Finally, the large degree of discretion granted to landowners by the U.S. Constitution (Smith 1993, Cullingworth 1997) means that conservation policy developed by government may have very little impact on what happens on the landscape. Unless we are content with merely cleaning up the infrastructure, it will be imperative to find ways to compensate private landowners for not developing their land. Rising to these challenges will require the development of strategies for conserving and managing biodiversity at multiple scales and the integration of actions by state, county, and municipal governments with those of landowners. This is a daunting task, but there are encouraging examples to guide our efforts (DeGrove 1992, Lee 1993, Beatley 1994, Duerksen et al. 1997). These multi-scale strategies must achieve reasonable compromises between maintaining local and regional diversity of species and habitats. Achieving conservation objectives in the face of rapid land-use change requires a new set of responses by scientists. We must assure that data and analyses are both readily understood and easily accessible to policy-makers and to the citizens who wish to influence decisions in established review processes. We must be willing to work locally to contribute to the solution of regional problems. Finally, we must emphasize that conservation should be focused on landscape mosaics, not habitat patches, and that developed areas are important components of these mosaics. Rather than writing off settled areas as having no conservation value, the challenge is to enhance the habitat value of these lands through better design. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank M. Hostetler, M. Alberti, and J. Marzluff for helpful suggestionson an earlier draft of this manuscript. REFERENCES Alberti, M., E. Botsford, and A. Cohen.2001. Quantifying the urban gradient: linking urban planning and ecology,p. 89-115.In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman,and R. Donnelly [EDS.], Avian ecology and conservationin an urbanizing world. Kluwer Academic, Norwell, MA. Aldrich, J. W., and R. W. Coffin. 1980. Breeding bird populationsfrom forest to suburbia after thirty-sevenyears.Amer. Birds 34:3-7. Anderson,J. R., E. E. Hardy, J. T. Roach, and W. E. Witmer. 1976. A land-useand landcover classification system for use with remote sensordata. USGS ProfessionalPaper 964. USGS,Reston,VA. 133 bird ecology H. 1992.Corvid density and nest predation in relation to forest fragmentation:a . . . . . Ecology 73:794-804. 1994.Habitatconservationplanning.University of TexasPress,Austin. S. R., and D. R. Osborne. 1982. Effects of urbanization on avian community . 1991.Roads,roadsidesand wildlife conservation:a review, p.99-117.In D. A. and R. J. Hobbs [EDS.],Nature conservation2: the role of corridors. Surrey , "- ~ L. 1990.Urbanization, p.103-t20./n B. L.t. Turner, W. C. Clark, R. W. Kates,J. T. Mathews,and W. B. Meyer [EDS.],The earthas transformedby human ~ . ~ 1996.Land-useand avian speciesdiversity along an urban gradient.Ecol. Appl. - - - -, ~ -. , --. 461-488. In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman, Donnelly [EDS.], Avian ecology and conservation in an urbanizing world. Kluwer - community,and landscapeapproaches,p. 155-177. In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman,and R. Donnelly [EDS.],Avian ecology and conservation in anurbanizingworld. Kluwer Academic,Norwell, MA. D. T., T. A. Scott, and J. T. Rotenberry. 1997. Breeding bird abundancein an ..11:406-421. A. Begazo.2001. Mccaw abundancein relationto humanpopulationdensity, p. 429-439.In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman, and R. Donnelly [EDS.],Avian ecology and conservationin an urbanizingworld. Kluwer Academic,Norwell, MA. 1989.Avian community structurein a large urban park: controls of local richness anddiversity.Land. Urban Plann. 17: 221-240. --~---, - -, J. P. L. Savard,G. Mennechez,and G. Falardeau.1998. Bird abundanceand diversity along an urban-rural gradient: A comparativestudy between two cities on differentcontinents.Condor 100:413-425. 1975.Towardsa theory of continentalspeciesdiversities:bird distributionsover mediterraneanhabitat gradients,p.214-257.In M. L. Cody and J. M. Diamond [EDS.], Ecologyandevolution of communities. HarvardUniversity Press,Cambridge,MA. , - - - - J .. - - --- JO . -.' growth: what are the linkages?,p.29-42. In S. T. A. Pickett [ED.],The ecologicalbasisof conservation:heterogeneity,ecosystems, andbiodiversity.Chapman& Hall, New York, NY. ~ , B. 1997.Planningin the USA: policies,issues,and processes. Routledge, London,England. Darveau,M., P. Beauchesne,L. Belanger,J. Huot, and P. Larue. 1995.Riparian forest strips ashabitatfor breedingbirds in borealhabitat.J. Wildl. Manage.59:67-78. DeGraaf,R. M., and J. M. Wentworth. 1986.Avian guild structureand habitatassociationsin suburbanbird communities.Urban Ecol. 9:399-412. DeGrove,J. M. 1992. Planning and growth managementin the States.Lincoln Institute of LandPolicy, Cambridge,MA. Duerksen,C. J., D. L. Elliot, N. T. Hobbs, E. Johnson,and J. R. Miller. 1997. Habitat protectionplanning:wherethe wild things are.Amer. PlanningAssoc.PlanningAdvisory ServoRep.No. 470-471. Engels,T. M., and C. W. Sexton. 1994. Negative correlation of Blue Jays and GoldencheekedWarblersnearan urbanizingarea.Conserv.BioI. 8:286-290. Ferris,C. R. 1979. Effects of Interstate95 on breedingbirds in northern Maine. J. Wildl. Manage.43:421-427. 134 Chapter6 Forman,R. T. T. 1995.Land mosaics.CambridgeUniversity Press,Cambridge,MA. Forman, R. T. T., and L. Alexander. 1998. Roadsand their major ecological effects. Ann. Rev. Ecology Syst.29:207-231. Fraterrigo,J. M. 2000. Low-density settlementin the Rocky Mountain West: effects on bird communities and landscapepatterns. M.S. thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins. Friesen,L. E., P. F. J. Eagles,and R. J. MacKay. 1995.Effectsof residentialdevelopmenton forest-dwellingneotropicalmigrant songbirds.Conserv.Bioi. 9:1408-1414. Gavareski,C. A. 1976. Relation of park size and vegetationto urban bird populationsin Seattle,Washington.Condor78:375-382. Geis, A. D. 1974.Effects of urbanizationand type of urbandevelopmenton bird populations, p.97-105. In J. H. Noyes and D. R. Progulski [EDS.], Wildlife in an Urbanizing Environment. November 27-29, 1973, Springfield, Massachusetts.University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Germaine, S. S., S. S. Rosenstock,R. E. Schweinsburg,and W. S. Richardson. 1998. Relationshipsamong breeding birds, habitat, and residential development in greater Tucson,Arizona. Ecol. Appl. 8:680-691. Gittens,R. 1968.Trend-surfaceanalysisof ecologicaldata.J. Ecology56:845-869. Green,R. J., C. P. Catterall, and D. N. Jones.1989.Foragingand other behaviourof birds in subtropicaland temperatesuburbanhabitats.Emu 89:216-222. Gustafson,E. J. 1998. Quantifying landscapespatial pattern: what is the state of the art? Ecosys.l:143-156. Guthrie, D. A. 1974. Suburbanbird populations in southern California. Am. MidI. Nat. 92:461-466. Hanowski,J. M., and G. J. Niemi. 1995.A comparisonof on- and off-road bird counts: Do you needto go offroad to count birds accurately?J. Field Ornithology66:469-483. Hargrove, W. W., and J. Pickering. 1992. Pseudo-replication:a sine qua non for regional ecology. LandscapeEcol. 6:251-258. Harris, L. D. 1988. Edge effects and conservationof biotic diversity. Conserv.BioI. 2:330332. Haskell, D., A. M. Knupp, and M. C. Schneider.2001. Nest predator abundanceand urbanization,p. 245-260.In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman,and R. Donnelly [EDS.],Avian ecologyand conservationin an urbanizingworld. Kluwer Academic,Norwell, MA. Hilden, O. 1965.Habitat selectionin birds. Ann. Zool. Fenn.2:53-75. Hodges, M. F. J., and D. G. Krementz. 1996. Neotropical migratory breeding bird communitiesin riparian forests of different widths along the Altamaha River, Georgia. Wilson Bull. 108:496-506. Hostetler,M. 2001. The importanceof multi-scaleanalysesin avian habitat selectionstudies in urban environments,p. 139-154. In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman, and R. Donnelly [EDS.],Avian ecology and conservation in an urbanizing world. Kluwer Academic, Norwell, MA. Howe, J., E. McMahon, and L. Propst. 1997. Balancing nature and commercein gateway communities. Island Press,Washington,DC. Jokimaki, J., and J. Suhonen. 1993. Effects of urbanization on the breeding bird species richnessin Finland: a biogeographicalcomparison.Ornis Fenn.70:71-77. Karr, J. R., and R. R. Roth. 1971. Vegetation structureand avian diversity in severalnew world areas.Am. Nat. 105:423-435. Knight, R. L., G. N. Wallace, and W. E. Riebsame.1995. Ranchingthe view: subdivisions versusagriculture.Conserv.BioI. 459-461. 6. Urban bird ecology 135 Knick,S. T., andJ. T. Rotenberry.1996.Landscapecharacteristicsof fragmentedshrubsteppe habitatsandbreedingpasserinebirds. Conserv.Bioi. 9:1059-1071. Knopf, F. L., and F. B. Samson. 1994. Scale perspectiveson avian diversity in western riparianecosystems.Conserv.Bioi. 8:669-676. Lee, K. N. 1993. Compass and gyroscope: integrating science and politics for the environment.Island Press,Washington,DC. Limerick,P. N. 1987.The legacyof conquest. W. W. Norton & Company,New York, NY. MacArthur,R. H., and J. W. MacArthur. 1961. On bird speciesdiversity. Ecology 42:594598. Major, R. E., G. Gowing, and C. E. Kendal. 1996. Nest predation in Australian urban environmentsand the role of the Pied Currawong, Strepera graculina. Aust. J. Ecol. 21:399-409. Marzluff,J. M. 2001. Worldwide increasein urbanizationand its effectson birds, p. 19-47.In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman, and R. Donnelly [EDS.],Avian ecologyand conservationin an urbanizingworld. Kluwer Academic,Norwell, MA. Marzluff,J. M., R. Bowman, and R. Donnelly. 2001. A historical perspectiveon urban bird research:trends,terms and approaches,p. 1-17. In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman, and R. Donnelly [EDS.], Avian ecology and conservation in an urbanizing world. Kluwer Academic,Norwell, MA. Marzluff,J. M., F. R. Gehlbach,and D. A. Manuwal. 1998.Urban environments:influences on avifauna and challengesfor the avian conservationist. In J. M. Marzluff and R. Sallabanks [EDS.], Avian conservation: research and management. Island Press, Washington,DC. Marzluff, J. M., and M. Restani. 1999. The effects of forest fragmentationon avian nest predation,p.155-169. In J. A. Rochelle,L. A. Lehmann,and J. Wisniewski [EDS.],Forest fragmentation.Wildlife and managementimplications.Brill, Leiden,the Netherlands. McDonnell, M. J., and S. T. A. Pickett. 1990. Ecosystemstructure and function along urban-ruralgradients:an unexploitedopportunityfor ecology.Ecology 71:1232-1237. Miller, J. R., and N. T. Hobbs.2000. Effects of recreationaltrails on nest predationratesand predatorassemblages. Land. Urban Plann.50:227-236. Miller, J. R., J. A. Wiens, and N. T. Hobbs. 2001. How does urbanization affect bird communitiesin riparian habitats?An approachandpreliminary assessment, p.427-439.In J. Craig,N. Mitchell, and D. Saunders[EDS.],Natureconservation5. Natureconservation in production environments:Managing the matrix. Surrey Beatty and Sons, ChippingNorton, New SouthWales,Australia. Mumme,R. L., S. J. Schoech,G. E. Wooflenden,and J. W. Fitzpatrick. 2000. Life in the fast lane: Demographicconsequences of road mortality in the Florida Scrub-Jay.Cons. Bioi. 14:501-512. Nelson,A. 1992.Characterizingexurbia.J. PlanningLit. 6:350-368. Nilon, C. H., C. N. Long, and W. C. Zipperer. 1995. Effects of wildland developmenton forestbird communities.Land. Urban Plann.32:81-92. NRCS. 1995. USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service, National Res. Inv. http://www.nhq.nrcs.usda.gov/NRI/tables/1992/table. 7.html. O'Dell, E. 2000. Wildlife communitiesand exurbandevelopmentin Pitkin County, Colorado. M.S. Thesis,ColoradoStateUniversity, Fort Collins. Osborne,P., and L. Osborne.1980.The contribution of nest site characteristicsto breedingsuccessamongBlackbirds Turdusmercula.Ibis 122:512-517. Ostrom,E. 1991.Managingthe commons.CambridgeUniversity Press,New York. Pearson,S. M. 1993.The spatial extent and relative influence of landscape-levelfactors on wintering bird populations.LandscapeEcol. 8:3-18. 136 Chapter6 Reijnen, R., R. Foppen, C. ter Braak, and J. Thissen. 1995. The effects of car traffic on breeding bird populations in woodland. 11\. Reduction in density in relation to the proximity of main roads.J. of Appl. Ecol. 32:187-202. Reijnen, R., R. Foppen, and H. Meeuwsen. 1996. The effects of traffic on the density of breedingbirds in Dutch agriculturalgrasslands.BioI. Conserv.75:255-260. Riebsame,W. E., H. Gosnell, and D. M. Theobald. 1996.Land-useand landscapechangein the Colorado mountainsI: Theory, scale,and pattern.Mount. Res. and Devel. 16: 395405. Robertson,G. P. 1987.Geostatisticsin ecology: Interpolatingwith known variance.Ecology 63:744-748. Rolando,A., G. Maffei, C. Pulcher,and A. Giuso. 1997.Avian communitystructurealong an urbanizationgradient.Italian J. of ZooI. 64:341-349. Romme,W. H. 1997.Creatingpseudo-rurallandscapesin the mountainwest, p.139-161. In J. I. Nassauer[ED.],Placingnature.IslandPress,Washington,DC. Saab,V. 1999.Importanceof spatial scaleto habitatuseby breedingbirds in riparian forests: a hierarchicalanalysis.Ecol. Appl. 9: 135-151. Saunders,D. A., R. J. Hobbs,and P. R. Ehrlich. 1993.Nature conservation3: Reconstruction of fragmented ecosystems,global and regional perspectives.Surrey Beatty & Sons, Chipping Norton, NSW, Australia. Savard,J. P. and J. B. Falls. 2001. Bird-habitat relationshipsof breedingbirds in residential areasof Toronto, Canada,p. 543-568.In J. M. Marzluff, R. Bowman, and R. Donnelly [EDS.],Avian ecology and conservation in an urbanizing world. Kluwer Academic, Norwell, MA. Schmidt,K. A. and C. J. Whelan. 1999.Effects of exotic Lonicera and Rhamnuson songbird nestpredation.Cons.BioI. 13: 1502-1506. Schneider,D. W. 1996. Effects of Europeansettlementand land-useon regional patternsof similarity amongChesapeake forests.Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 123:223-239. Schwartz,M. W. 1997. Conservationin highly fragmentedlandscapes.Chapman& Hall, New York, NY. Small, M. F., and M. L. Hunter. 1988. Forest fragmentationand avian nest predation in forestedlandscapes.Oecologia76:62-64. Smith, H. H. 1993. The citizen's guide to planning. American Planning Association, Chicago,IL. Sodhi, N. S. 1992. Comparison between urban and rural bird communities in prairie Saskatchewan:urbanizationand short-termpopulation trends. Can. Field-Nat. 106:210215. Stauffer, D. F., and L. B. Best. 1980. Habitat selectionby birds of riparian communities: evaluatingeffectsof habitatalterations.J. Wildl. Manage.44:1-15. Szaro,R. C., and M. D. JakIe. 1985. Avian use of a desertriparian island and its adjacent scrubhabitat.Condor87:511-519. Terborgh, J. 1971. Distribution on environmental gradients: theory and a preliminary interpretationof distributional patterns in the avifauna of the Cordillera Vilcabamba, Peru.Ecology52:23-40. Theobald,D.M. 2000. Fragmentationby inholdingsand exurbandevelopment,p.155-174. In R.L. Knight, F.W. Smith, S.W. Buskirk, W.H. Romme,and W.L. Baker, [EDS.],Forest fragmentationin the central Rocky Mountains.University Pressof Colorado,Boulder. Theobald,D.M. and N. T. Hobbs. 1998. Forecastingrural land-usechange:a comparisonof regression-and spatialtransition-basedmodels.Geog.Env. Mod. 2: 57-74. 6. Urban bird ecology 137 Theobald,D. M., N. T. Hobbs,T. Bearly, J. A. Zack, T. Shenk,and W. E. Riebsame.2000. Incorporating biological information in local land-use decision making: designing a systemfor conservationplanning.LandscapeEcol. 15: 35-45. Theobald,D. M., J. R. Miller, and N. T. Hobbs. 1997:Estimatingthe cumulativeeffects of developmenton wildlife habitat.Land. Urban Plann.39:25-36. Tilghman,N. G. 1987. Characteristicsof urban woodlandsaffecting breedingbird diversity andabundance.Land. Urban Plann. 14:481-495. Tumer, M. G., R. H. Gardner, and R. V. O'Neill. 2000. Pattern and process:landscape ecologyin theory and practice.Springer-Verlag,New York. UnitedNations Centre for Human Settlements.1996.An urbanisingworld: global report on human settlements,1996. Oxford University Pressfor the United Nations Centre for HumanSettlements(Habitat), Oxford, United Kingdom. US Bureauof the Census.1998. Statistical abstractof the United States.U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington,DC. Vale, T. R., and G. R. Vale. 1976. Suburbanbird populationsin west-centralCalifornia. J. Biogeogr.3:157-165. vanDer Zande,A., W. Ter Keurs, and W. Van Der Weijden. 1980.The impact of roads on the densitiesof four bird speciesin an open field habitat - evidenceof a long-distance effect.Bioi. Conserv.18:299-321. Whittaker,R. H. 1967.Gradientanalysisof vegetation.Bioi. Rev.42:207-264. Wiens,J. A. 1989.Spatialscalingin ecology.Func. Ecol. 3:385-397. Wiens,J. A., and J. T. Rotenberry. 1981. Habitat associationsand community structure of birds in shrubsteppeenvironments.Ecol. Monogr. 51:21-41. Willson, M. F. 1974.Avian community organizationand habitat structure.Ecology 55:10171029.