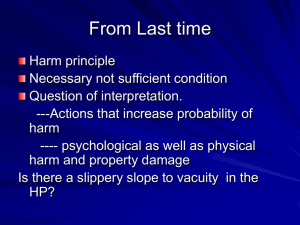

WRONGFUL LIFE, PROCREATIVE RESPONSIBILITY, AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HARM

advertisement