Politics and the Social Contract: John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau

advertisement

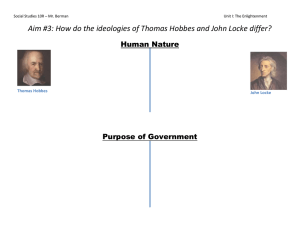

Politics and the Social Contract: John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau Clark Wolf Iowa State University jwcwolf@iastate.edu Argument for Analysis Since people have fundamentally equal rights and abilities, radically unequal distribution of wealth and goods is fundamentally unjust. But where political institutions protect rights to private property, radical inequalities are sure to arise. Since the right to property leads to injustice, property rights are unjust. Argument for Analysis If property rights can arise without the violation of anyone’s rights, then property rights are permissible. If property rights are required for implementation of Natural Law, then property rights are required by justice. But the protection of property rights leads to radical inequalities. It follows that radical inequalities are sometimes consistent with justice. NOTICE: Those who would like to re-take midterm or Quiz may do so on Friday between 2:00 and 3:00. Catt Hall 407. If you can’t make it then, see me! Anyone may re-take these exams. The new grade will not replace the old, but will be taken into account in your final grade for the course. Argument for Analysis Locke argues that we can gain property in land by “mixing our labor” with it, as long as we don’t appropriate more than we can use without waste, and as long as we leave “enough and as good” for others. But Locke’s theory can’t justify existing property rights: the world is finite, and the human population of the earth is large. At this point, there is no land left to appropriate. So previous appropriation cannot have left “enough and as good” in the common, so it must have violated the ‘enough and as good’ requirement. So on Locke’s view, existing property rights in land are illegitimate. Argument for Analysis 1) Locke specifies that legitimate appropriation must leave ‘enough and as good’ for others. 2) At present there is no land left in a common. 3) previous appropriation did not leave “enough and as good” in the common. 4)Previous appropriation was unjustified. 5) on Locke’s view, existing property rights in land are illegitimate. Argument for Analysis The political theories of Hobbes and Locke are irrelevant. Hobbes and Locke both describe civil government as arising from a pre-social state of nature, where society is unorganized and has no strucuture. But people have never lived in such a state, so we can’t learn anything about real societies by looking at such an artificial construct. 1) Hobbes and Locke both describe civil government as arising from a pre-social state of nature, where society is unorganized and has no structure. 3) But people have never lived in such a state, so 4) we can’t learn anything about real societies by looking at such an artificial construct. 5) [IP] If we can’t learn anything about real societies from the works of a political theorist, then that theorist’s work is irrelevant. 6) The political theories of Hobbes and Locke are irrelevant. Two kinds of answer: 1) People really are (or have been) in a ‘state of nature.’ 2) Conceiving of political institutions on the model of a contract can still inform us about their essential properties. Argument for Analysis: Soujourner Truth, Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio, 1851: “Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that 'twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all this here talking about? That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mudpuddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman? Then they talk about this thing in the head; what's this they call it? [member of audience whispers, "intellect"] That's it, honey. What's that got to do with women's rights or negroes' rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn't you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full? Then that little man in black there, he says women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wasn't a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him. If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back , and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them. Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain't got nothing more to say.” Argument for Analysis Either I’ll stay on campus between classes, or I’ll go home. If I go home, my roommate will distract me and I won’t get my Philosophy reading done. But if I stay on campus, I won’t have anyplace quiet to work, so I won’t be able to get my philosophy reading done. I guess I won’t get my reading done! Argument for Analysis 1) Either I’ll stay on campus between classes, or I’ll go home. 2) If I go home, my roommate will distract me and I won’t get my Philosophy reading done. 3) But if I stay on campus, I won’t have anyplace quiet to work, so I won’t be able to get my philosophy reading done. 4) I won’t get my reading done! Dilemma 1) Either C or H 2) If H then D & ~P 3) if C then ~W and ~P. 4) ~P Argument for Analysis If we arm campus police, then there will be more guns on campus because the campus police will bring them. But if we don’t arm campus police, then the criminals will bring more guns to campus. So no matter what we do, there will be more guns on campus. If there are guns on campus, it’s better that they be in the hands of the police than in the hands of the criminals. So we should arm the police. Argument for Analysis There can be no such thing as justice unless there are institutions to punish people who break their promises and contracts. Justice involves the rational requirement that people should keep their promises and abide by the contracts to which they freely agree. But unless there are public institutions that will punish people who break promises and contracts, it is not rational for people keep them. Since requirements of justice must be requirements of reason (rationality), it isn’t ‘just’ to keep contracts where there is no punishment, it’s just irrational and foolish. Argument for Analysis 1) Justice involves the rational requirement that people should keep their promises and abide by the contracts to which they freely agree. 2) But unless there are public institutions that will punish people who break promises and contracts, it is not rational for people keep them. 3) Since requirements of justice must be requirements of reason (rationality), it isn’t ‘just’ to keep contracts where there is no punishment, it’s just irrational and foolish. 4) There can be no such thing as justice unless there are institutions to punish people who break their promises and contracts Argument for Analysis Terms like ‘good’ and ‘beautiful’ essentially refer to the attitudes of the person who uses them: to say that something is beautiful is to say that one likes looking at it; to say that something is good is to say that one appproves of it. Since different people find different things beautiful and good, such terms change their meaning when they are used by different people. But reasoning requires terms that have a stable meaning: proper reasoning cannot be done with terms that have a different meaning for different speakers. Ethics is the philosophy of ‘good,’ just as aesthetics is the philosophy of ‘beauty.’ It follows that there can be no reasoning in ethics or aesthetics. Argument for Analysis 1) Ethics is the philosophy of ‘good,’ just as aesthetics is the philosophy of ‘beauty.’ 2) To say that something is beautiful is to say that one likes looking at it; to say that something is good is to say that one approves of it. 3) Since different people find different things beautiful and good, such terms change their meaning when they are used by different people. 4) Reasoning requires terms that have a stable meaning 5) Therefore, there can be no reasoning in ethics or aesthetics. Language and Knowledge: Right Definitions and the "Sticky twigs of language..." "Seeing that truth consisteth in the right ordering of names in our affirmations, a man that seeketh precise truth had need to remember what every name he uses stands for, and to place it accordingly; or else he will find himself entangled in words, as a bird in lime twigs, the more he struggles the more belimed. And therefore in geometry, (which is the only science that it hath pleased God hitherto to bestow on mankind) men begin at settling the significations of their words; which settling of significations they call definitions and place them in the beginning of their reckoning." -Leviathan, Ch 4, p. 501. Reason: REASON... is nothing but reckoning (that is, adding and subtracting) of the consequences of general names agreed upon for the marking and signifying of our thoughts. (Ch 5, p. 503) Knowledge: Hobbes is an Empiricist. Knowledge comes from our senses. False and misleading ideas we get are added by imagination and "fancy." Empiricism: The theory that all knowledge comes to us through the senses. Insignificant Speech: Literally meaningless noise presented under the false guise of communication. Hobbes believes that we become literally incoherent when we are not careful about the meanings of the terms we employ. "The common sort of men seldom speak insignificantly, and are therefore by those other egregious persons counted idiots. But to be assured their words are without any thing correspondent to them in the mind, there would need some examples; which if any man require, let him take a School-man into his hands and see if he can translate any one chapter concerning any difficult point, as the Trinity; the Deity; the nature of Christ' transubstantiation; free-will, &c. into any of the modern tongues, so as to be able to make the same intelligible. (...) What is the meaning of these words: "The first cause does not necessarily inflow anything into the second, by force of the essential subordination of the second causes, by which it may help it to work." They are the translation of the title of the sixth chapter of Suarez' first book, Of the Concourse, Motion, and Help of God. When men write whole volumes of such stuff, are they not mad, or intent to make others so?" (Ch 8, end, p. 617) Hobbes on Philosophical Nonsense: Philosophers are the worst, according to Hobbes: "And of men, those are of all most subject to [absurdity] that profess philosophy. For it is most true that Cicero saith of them somewhere; that there can be nothing so absurd but may be found in the books of philosophers." (Ch 5p. 504) The Point: Hobbes hopes to clear up earlier philosophical messes by making language precise. He hopes to do for politics, morals, and knowledge, what Euclid did for Geometry. Hobbes on Psychology and Human Motivation: Psychological Egoism: All human actions are (ultimately) selfish. Ethical Egoism: All right actions are selfish. Questions: 1) Why would anyone believe these theories? 2) Are these two consistent with one another? Why or why not? 3) Is Hobbes a psychological egoist? 4) Is Hobbes an ethical egoist? POWER AND DEATH: THE BASIC HOBBESIAN MOTIVES: "I put for a general inclination of all mankind, a perpetual and restless desire for power after power, that ceaseth only in death. And the cause of this is not always that a man hopes for a more intensive delight than he has already attained to; or that he cannot be content with a moderate power: but because he cannot assure the power and means to live well, which he hath present, without the acquisition of more. And from hence it is that Kings, whose power is greatest, turn their endeavours to the assuring it at home by laws or abroad by wars: and when that is done, there succeedeth a new desire; in some of fame from new conquest: in others, of ease and sensual pleasure; in others, of admiration, or being flattered for excellence in some art, or other ability of the mind." (Ch 11 p. 523) Hobbesian Psychology: Egoism? IS HOBBES A PSYCHOLOGICAL EGOIST? For: He does seem to define our words in the language of self-interest... Against: Not all of our interests may be selfregarding. When we act on other-regarding interests, we're not egoists. In MAN AND STATE Hobbes makes it clear that he is not a psychological egoist. (Good thing too, since no reputable psychologist now regards psychological egoism as a plausible theory of human motivation.) Value: Value and "Good:" "Whatsoever is the object of any man's appetite or desire, that it is which he for his part calleth good; and the object of his hate and aversion, evil and of his contempt vile and inconsiderable. For these words of good, evil, and contemptible, are ever used with relation to the person that useth them: there being nothing simply and absolutely so; nor any common rule of good and evil, to be taken from the nature of objects themselves; but from the person of the man. (...)" (Ch 6, p. 506) Value Realism and Value Subjectivism Compare: Hamlet: "...there's nothing good or bad but thinking makes it so." Epictetus: Things are not good or bad in themselves, but only in relation to our desires and aversions. So it's 'bad' to want something and not get it, or to be averse to something and get it. [But, Epictetus will go on, if you train yourself not to want or be averse to the wrong things, then nothing will be good or bad for you.] BUT BY CONTRAST: Compare Plato on "Good." What is Plato's reason for thinking that "good" can be a non-subjective term? Does Plato's reason apply to Hobbes' theory? Terms of "inconstant signification" and reasoning: a source of "insignificant speech": "The names of such things as affect us, that is, which please and displease us because all men be not alike affected with the same thing, nor the same man at all times, are in the common discourses of men of inconstant signification. For seeing all names are imposed to signify our conceptions, and all our affections are but conceptions, when we conceive the same things differently, we can hardly avoid different naming of them. For though the nature of that we conceive, be the same; yet the diversity of our reception of it, in respect of different constitutions of body and prejudices of opinion, gives every thing a tincture of our different passions. And therefore in reasoning a man must take heed of words which besides the signification of what we imagine of their nature, have a signification also of the nature, disposition, and interest of the speaker; such as are the names of virtues and vices; for what one man calleth wisdom another calleth fear, and one cruelty what another justice, one prodigality what another magnanimity, and one gravity what another stupidity, &c. And therefore such names can never be true grounds of any ratiocination." (Ch 4, end p. 502) Paradiastole [OED 2071]: "A figure in which a favorable turn is given to something unfavorable by the use of an expression that conveys only part of the truth... When with a milde interpretation or speech we colour others or our own faults, as when we call a subtile man wise, a bold fellow courageous, or a prodical man liberal... pradastiole by some learned Rhetoriticians called a faulty turn of speech, opposing the truth by false terms and wrong names. [You will not be asked to define this on an exam!] Example from Plato: Conversation between Clessippus and Dionysdorus from Plato's Euthydemus: “You say that you have a dog?” “Yes, a villain of one,” said Clesippus. “And he has puppies?” “Yes, and they are very like himself.” “And the dog is the father of them?” “Yes,” he said, “I certainly saw him and the mother of the pupps come together.” “And is he not yours?” “To be sure he is.” “Then he is a father, and he is yours, ergo he is your father, and the puppies are your brothers!” The Point: Hobbes believed that fallacious arguments like these could be avoided, if only we take care to use words carefully, according to firm, supportable definitions. Hobbes on Values and Reasoning: Implications for a Philosophy of "Good:" 1) Evaluative terms like 'good' 'bad' 'better' 'worse' are perspectival. 2) Perspectival terms cannot be the basis for reasoning. 3) Therefore there can be no reasoning about what is good or bad or better or worse. Question: How would Aristotle or Plato respond to Hobbes Argument? Where have we seen a position like this before? (Thrasymachus in Plato's Republic, Book I!) Hobbes's State of Nature and the Foundations of Civil Society The Question: Given Hobbes' account of human motivation and the desire for power (and fear of death), how is it possible for human beings to cooperate with one another in society? How could we move from a presocial situation (a state of nature) into a civil society with laws and government? What do we gain (and loose) in the transition from the state of nature to the state of civil society? Hobbes’s State of Nature: Rough Equality, No exclusive rights to anything. "Nature hath made men so equal, in the faculties of body and mind' as that though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body, or of quicker mind than another' yet when all is reckoned together, the difference between man and man is not so considerable as that one man can thereupon claim to himself any benefit to which another may not pretend as well as he. For as to the strength of body, the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination, or by confederacy with others that are in the same danger with himself." (Ch 13 p. 531) State of Nature is a State of War: "And from this equality of ability, ariseth equality of hope in the attaining of our ends. And therefore if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies; and in the way to their end, endeavor to destroy or subdue one another. (Ch 13, p. 531) War and the Causes of Quarrel: "In the nature of man, we find three principle causes of quarrel. First competition, second, diffidence, thirdly glory. The first maketh men invade for gain, the second for safety, the third for reputation. The first use violence to make themselves masters of other mens persons, wives, children, and cattle; the second to defend them; the third for trifles as a word, a smile, a different opinion, and any other sign of undervalue." (632) State of Nature is a State of War: "Hereby it is manifest that during the time men live without a common power to keep them in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man." (632) Why War is Bad: What is life like in the "state of nature," this war of "all against all? "In such condition there is no place for industry because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation; nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force' no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man solitery, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." (632-33) Justice in War, and the Prospects for Peace: In such circumstances all talk of justice is meaningless, claims Hobbes: "To this war of every man against every man, this also is consequent. That nothing can be unjust. The notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice have there no place. Where there is no common power, there is no law, where no law no injustice. Force and fraud are in war the two cardinal virtues. justice and injustice are none of the faculties neither of the body nor mind.(...) The passions that incline men toward peace are fear of death, desire of such things as are necessary to commodious living, and a hope by their industry to obtain them. And reason suggesteth convenient articles of peace, upon which men may be drawn to agreement. These articles are they which otherwise are called the Laws of Nature whereof I shall speak more particularly in the following two chapters. (633) COMPETITION, GLORY, AND THE CAUSES OF WARRE!! To the State of "Warre" Equality + [Competition, "Diffidence," and "Glory"] => WARRE of all against all. Competition: Limited goods, we all want 'em. Diffidence: We all fear for our safety and mistrust others. Glory: Desire for reputation; over-estimating our own capacities, underestimating costs of war. Law and Right Natural Laws and Natural Rights Right: What you can do without obstruction Law: A constraint on liberty. Hobbesian Right of Nature: The liberty to use one's power to protect one self however one sees fit to do it. Hobbesian Laws of Nature: rules of reason that tell us to do what it is in our interest to do. Right of Nature in the SON: Right of Nature: In the SON (State of Nature), everyone has a right to everything. "And because the condition of man is a condition of war of everyone against everyone, in which case everyone is governed by his own reason and there is nothing he can make use of that may not be a help unto him in preserving his life against his enemies, if followeth that in such a condition everyone has a right to every thing, even to one anothers' body. And therefore as long as this natural right of every man to every thing endureth, there can be no security to any man, (how strong or wise soever he be), of living out the time which nature ordinarily alloweth men to live. And consequently it is a precept, or general rule of reason that every man ought to endeavour peace as far as he has hope of attaining it; and when he cannot obtain it, that he may seek and use all helps and advantages of war. The first branch of which rule containeth the first and fundamental law of nature which is to seek peace and follow it. The second the sum of the right of nature which is by all means we can, to defend ourselves.” Laws of Nature in SON: First Law of Nature: [80] Seek peace. Second Law of Nature: "...that a man be willing, when others are so too, as far-forth for peace and defense of himself he shall think it necessary, to lay down this right to all things and be contented with so much liberty aggainst other men as he would allow other men against himself. For as long as every man holdeth this right of doing anthing he liketh, so long are all men in the condition of war. But if other men will not lay down their right, as well as he, then there is no reason for anyone to divest himself of his: for that were to expose himself to prey (which no man is bound to) rather than to dispose himself to peace. This is that law of the Gospel; whatsoever you require that others should do to you, that do ye to them. (636) Second Law of Nature: Be willing to contract to lay down some of the liberties implicit in right of nature to seek peace, but only when others are also willing. The Prisoners’ Dilemma The Original Prisoner's Dilemma: Avery and Terry have been captured during the commission of a minor crime, but the DA knows that they are guilty of a much more serious crime, which they committed together. The DA places them in separate rooms, and says to each one: If either of you individually confesses and turns states evidence on your accomplice, you will be set free. But if your accomplice confesses and turns states evidence while you keep silent, we will punish you with the full force of the law: In this case, 50 years in prison. If you both turn states evidence, we will punish you only a little bit less severely: you will each receive 49 years in prison. However, if neither of you confess, the most we can give you for your minor crime is that you will both receive one year in prison. The Prisoners’ Dilemma In the table below, outcomes are represented in "years in prison," with Avery's sentence first and Terry's sentence later so that [0,50] refers to the outcome in which Avery goes free (0 years in prison) and Terry gets a 50 year sentence. Payoffs are represented in years in prison, and as ordered pairs: [Payoff for Avery, Payoff for Terry] Action of Terry Action of Avery Keep Silent Turn State’s Evidence Keep Silent [1,1] Second best for both, and really not that bad. [50,0] Worst for Avery, best for Terry Turn State’s Evidence [0,50] Worst for Terry, Best for Avery [49,49] Third best for both, and almost as bad as the worst. Prisoners’ Dilemma: The Dominance Argument Dominance Argument: If each wants to minimize years spent in prison, then Avery and Terry should both reason as follows: The other person will either choose to keep silent, or to turn state's evidence. "cooperate" or to "defect." I can not influence the choice that person makes-- in this sense, it is as if the choice has already been made. Suppose my partner turns states evidence: Then the only outcomes I could achieve are 45 year in prison (if I also turn states evidence) or 50 years in prison (if I keep silent). Better 45 years in prison than 50 years, so if I knew that my partner was planning to sell me down the river I wouldn't want to be a sucker: I would want to turn states evidence too. Suppose my partner keeps silent: Then the outcomes available to me include freedom (if I turn evidence) or one year in prison (if I keep silent too). Freedom is better than a year in prison, so if I knew that my partner was planning to keep silent, then it would be better for me to defect. It follows that no matter what the other person does, I will minimize my years in prison if I turn states evidence. A choice is Dominant just in case it’s the best choice no matter what other people do. So breaking trust is a Dominant Strategy. Prisoners’ Dilemma: Some Terms Dominant Strategy: A strategic option dominates alternatives just in case the actor is better off choosing this option no matter what anyone else does. Nash Equilibrium: The outcome achieved if each "player" adopts an individually rational strategy. [Which outcome in the matrix above is the Nash Equilibrium?] Cooperative Outcome: The outcome achieved if both "players" cooperate with one another rather than defecting. [In the example above, the outcome in which we both keep silent is the cooperative outcome.] Pareto Optimum: An outcome is a pareto optimum if there is no alternative outcome that is preferred by at least one person which is not worse for some other. Paradox: In the "Prisoner's Dilemma," the Nash equilibrium is worse for both. So if both players are “rational” and make the choice that is likely to maximize individual benefit, the outcome is worse for both. In the prisoners’ dilemma, the ‘rational’ outcome is not the pareto optimum. Does this ever really happen? From Prisoners’ Dilemma to Public Goods to Commons Tragedy ...the coral reefs of the Philippean and Tongan islands are currently being ravaged by destructive fishing techniques. Where fishermen once used lures and traps, they now pour bleach (i.e. sodium hypochlorite) into the reefs. Partially asphyxiated, the fish float to the surface and become easy prey. Unfortunately, the coral itself suffocates along with the fish, and the dead reef ceases to be a viable habitat. ("Blast fishing," also widely practiced, consists of using dynamite rather than bleach.) What goes through the minds of these fishermen as they reduce some of the most beautiful habitats in the world to rubble? Perhaps some of them think, quite correctly, that if they do not destroy a given reef, it will shortly be destroyed by someone else, so they might as well be the ones to catch the fish. -David Schmidtz, “The Limits of Government.” From Prisoners’ Dilemma to Public Goods to Commons Tragedy Everyone Else Fish with lures and traps Fish with Dynamite and Bleach Me Fish with Lures and Resource is preserved, Traps we all catch less fish. Resource is destroyed, and I catch less than anyone else. Fish with Dynamite Resource is preserved and Bleach (my destruction isn’t enough to waste the resource) and I get lots of fish! Resource is destroyed and at least I get as much as everyone else. Prisoners’ Dilemmas and Commons Tragedies: Thomas Hobbes on Covenants in the State of Nature: (Leviathan, Part I, Chapter 14) "If a covenant be made, wherein neither of the parties perform presently, but trust one another; in the condition of mere nature, (which is a condition of war of every man against every man,) upon any reasonable suspicion, it is void: but if there be a common power set over them both, with right and force sufficient to compel performance, it is not void. For he that performeth first has no assurance that the other will perform after; because the bonds of words are too weak to bridle men's ambition, avarice, anger, and other passions, without the fear of some coercive power; which in the condition of mere nature, where all men are equal and judges of the justness of their own fears, cannot possibly be supposed. And therefore he which performeth first, does but betray himself to his enemy; contrary to the right (he can never abandon) of defending his life, and means of living." The Single-Shot Crop Harvesting Dilemma: I need your help to bring in my crop of grain, which ripens in late summer. You will need my help to bring in your apples which ripen in early fall. Can we achieve an agreement to cooperate? Not in the state of nature, implies Hobbes. Your choice in late summer: Help me or don't help me. My choice comes in early fall: Help you (keep my "contractual promise") or don't help you (break my promise). Payoffs in the matrix below are given in terms of the rank order of the outcome in question for [Me, and You]. So [1,3] means that the box in question is my first choice outcome and your third choice outcome. You Me Help me this summer Don’t Help me Help you in Fall [2,1] Second best for me, best you can hope for. This outcome is not achievable, since I won’t help you unless I’m compensated. Don’t help you in the Fall (Break my “promise”) [1,3] Best for me, since I gain your cooperation at no cost. (Worst for you, Sucker!) [3,2] Third best for me, since I’d rather cooperate than not. Second best for you, since at least you’re not exploited by your unscrupulous neighbor. The Elemental Form of the Prisoners’ Dilemma In the box below, outcomes are identified as 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th choice preferences instead of quantitative payoffs. You Me Cooperate Defect Cooperate [2,2] [4,1] Defect [3,3] [1,4] The Elemental Form of the Prisoners’ Dilemma Sadly, the Logic works the same even when the cooperative benefit is only slightly less than the exploitation payoff: the downside risk that one might get the “sucker payoff” if one cooperates is sufficient to make it narrowly “rational” to defect every time. In the matrix below, payoffs represent the prize or reward that each person will get: You Me Cooperate Cooperate [$99.99,$99.99] [0,$100] Defect [$100,0] Defect [$.01,$.01] Conditions for a Commons Tragedy: Nonrivalrous Consumption: One person’s consumption of the good does not prevent others from enjoying it as well. Non-Excludability: Noncontributors (or noncooperators) cannot be excluded from using the common. In fact, these conditions are a matter of degree. Few resources are purely nonrivalrous or purely nonexcludable. Two Problems that Create a PD or Commons Tragedy: ASSURANCE PROBLEM: Even if people would prefer to cooperate might not be willing to do so unless they can be assured that others would also cooperate. (Shows that good will is not enough) COORDINATION PROBLEM: People might be willing to cooperate IF ONLY they could coordinate their actions, but they may be unable to achieve the necessary coordination to make cooperation worth-while. (Shows that good will is not enough, even if people know that others are good willed) Hobbes on the Problems in the SON No way to coordinate no way to cooperate no way to promise, even when it would be better for all No way to make covenants no way to be secure in property no way to gain fruits of prudence or creativity No possibility for 'Justice' in the SON: "Covenants without the sword are but words..." (Ch 17) The Prisoners’ Dilemma In the table below, outcomes are represented in "years in prison," with Avery's sentence first and Terry's sentence later so that [0,50] refers to the outcome in which Avery goes free (0 years in prison) and Terry gets a 50 year sentence. Payoffs are represented in years in prison, and as ordered pairs: [Payoff for Avery, Payoff for Terry] Action of Terry Action of Avery Keep Silent Turn State’s Evidence Keep Silent [1,1] Second best for both, and really not that bad. [50,0] Worst for Avery, best for Terry Turn State’s Evidence [0,50] Worst for Terry, Best for Avery [45,45] Third best for both, and almost as bad as the worst. Hobbes Solution: The State as Crime Boss What happens to the Prisoners’ Dilemma if we add a “crime boss” who will murder anyone who rats on another member of the Gang? Action of Avery Action of Terry Keep Silent Turn State’s Evidence Keep Silent [1,1] Each gets one year in prison. First choice for both! [50,0 + dead] Bad for Avery who gets 50 yrs. Worst for Terry who gets dead. Turn State’s Evidence [0 + dead, 50] Bad for Terry who gets 50 yrs. Worst for Avery who gets dead [dead, dead] Worst for both, since the kingpin rubs them both out. On the Hobbesian Solution: Upshot: With a crime kingpin, ‘Keeping silent’ becomes a dominant strategy for both, and they can achieve cooperation. According to Hobbes, this is what the threat of legal sanction does for us all. The function of the state is to hold a sword over our heads and threaten us into behaving well. This, he argues, will solve the problem of the commons! While it is usually a disadvantage to have someone holding a sword (or a threat) over your head, Hobbes shows that it can sometimes be an advantage. The modern correlate of the Hobbesian view is the theory that commons problems must be solved by restrictive legislation. Sadly, this may sometimes be the only way to go. “Covenants without the sword are but words, with no strength to secure a man at all.” -Thomas Hobbes Hobbes and the Foole: 1) Hobbes urges, contrary to the “Foole,” that justice not contrary to reason 2) He argues that ‘covenant breakers’ must be excluded from society QUESTION: How can people lay down their rights to a sovereign? All must act at ONCE, else it's no good. (Coordination and assurance problems arise here too.) From Hobbes to Locke… John Locke: Second Treatise of Government Locke's State of Nature: 1) State of "Perfect Freedom," but within the "law of nature." 2) State of "natural equality." Locke refers not only to (rough) equality of abilities and capacities, but also to the fact that all are equally bound by the law of nature. AN OBJECTION TO HOBBES: Without initial honesty and truth telling, we can't leave SON. Once we GET a sovereign, Hobbes has no problem, but before the sovereign, we can't contract. The Upshot: We can’t make a social contract unless one is already in place. LOCKE'S SOLUTION: "Truth and keeping faith belongs to men as men, and not as members of society."(745*) ROUSSEAU 1) Is social inequality natural or artificial? [In Rousseau's work, this seems to be a question about the justification of inequality: Are vast inequalities justified by the law of nature or are they unjustifiable and horrible?] 2) What social circumstances make it possible for some people to subjugate and enslave others? 3) What features of human beings are natural, and what features are social accretions? And how can we tell? 4) When we look around the world, we see people oppressing one another and perpetrating unspeakable violence on one another. What makes people capable of such brutality? What must a person believe or desire in order to have the ability to brutalize other human beings? PROPERTY, EQUALITY, AND DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE The Problem of Distributive Justice:How should the burdens and benefits of social organization be distributed? Egalitarianism: These goods (and bads) should be distributed equally. People should not be treated differently unless there are good justifying reasons for unequal treatment. PROPERTY, EQUALITY, AND DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE Rousseau: "...since inequality is practically non-existent in the SON, it derives its force and growth from the development of our faculties and the progress of the human mind, and eventually becomes stable and legitimate through the etablishment of property and laws. Moreover, it follows that moral inequality, authorized by positive right alone, is contrary to natural right whenever it is not combined in the same proportion with physical inequality" a distinction that is sufficient to determine what one should think in this regard about the sort of inequality that reigns among all civilized people, for it is obviously contrary to the law of nature, however it be defined, for a child to command an old man, for an imbecile to lead a wise man, and for a handful of people to gorge themselves on superfluities while the starving multitude lacks basic necessities." PROPERTY, EQUALITY, AND DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE Propertarianism: (Locke) Give to each person what she or he is entitled to. People own whatever they legitimately acquire. Acquisition is either creation, original appropriation, or transfer from another legitimate owner. What considerations support property rights (Lockean or otherwise)? The notion that people are entitled to things they've made with their own efforts is ancient, and has roots in widely divergent social traditions. It may not be "natural" in the sense that Locke thinks: the laws of Acquisition don't seem to be objective universal truths like the laws of physics or mathematics. But they may be natural in the sense that it's easy to understand how people could come to feel proprietary. Where laborers have been forced to work without gaining any entitlement to the fruits of their labor, they have often resented their situation as unjust. PROPERTY, EQUALITY, AND DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE What considerations support egalitarianism? The notion that social institutions should treat people equally also has an ancient history, and once again the idea has sprung up in widely different societies around the world. Oddly enough, equality seems most likely to be articulated as an ideal in societies that are most flagrantly inegalitarian. Question: Are these conceptions of justice "natural?" What would it mean for a conception of justice to be "natural?" Perhaps not in the sense Locke implies. But it may be that common properties of human beings and common features of the human condition lead people to develop notions of property and equality, and to regard these notions as a kind of ideal. PROPERTY, EQUALITY, AND DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE PROBLEM: These two conceptions of distributive justice are not compatible. Where property rights are guarded, ineqalities will eventually arise. Over time, inequalities will become more pronounced, until eventually some are extravagantly wealthy while others are destitute. [Or so argues Rousseau. Was he wrong?] Locke's Solution: Property rights are clearly OK (they're part of Natural Law). So if property rights generate inequalities, then some inequalities must be OK. As long as no one's rights are violated, there's no limit to the extent of justified inequalities. Rousseau's Solution: Extreme Inequalities are pernicious, oppressive, and clearly can't be justified as part of the "Natural" order of things. If property rights are sure to generate these inequalities, then property rights must be illegitimate (un-natural). Rousseau’s Conjectural History 1) "Natural Man" (Sprung from the ground overnight, full grown like a mushroom; expresses many of Rousseau's own prejudices and idealizations) 2) Families stay together 3) Villages of families (tools & huts). (876) [There are problems already at this stage: (877).] 4) Agriculture (property rights arrive on the scene...) (878) [Dependence introduces possibility of oppression: (878)] 5) Notions of Right and Justice set in stone the oppression of the weak, lead them to see their oppression as part of the natural order of things. (Locke, Hobbes) 6) Devotion to Abstractions like Natural Right and Natural Law (These are just artificial creations, says Rousseau.) 7) Nationalism: Devotion to abstractions of group identity. (889) (Atrocities become possible.) Rousseau’s Conjectural History The Psychology of Rousseau's "Natural" Human Being: 1) Two Principles of Natural Motivation: Empathy and Self Interest. 2) Hobbes was wrong to suggest that lacking an idea of goodness, human beings would be vicious. [868] (Did Hobbes really hold this view?) 3) Pity a natural disposition to virtue (869) 4) Sentience, not rationality, is source of moral concern. (870) 5) Other virtues spring from pity (870) 6) Reason can eliminate this natural source of virtue. (870) 7) Philosophical accounts of morality always get things wrong. (855) 8) Pity takes the place of Law in the SON (870) Rousseau’s Conjectural History Question: There are many points at which some of us probably don't agree with Rousseau. If we're unconvinced by his account of "Natural Human Beings," does it follow that his account of oppression and inequality is also flawed? Consider the reasons he gives why we should believe the account he gives: (883) 1) supposed "right of conquest" could not arise in any other way. (Referring to the notion that the wealthy are justified as Conquerors) 2) words "strong" and "weak" are equivocal, since we're naturally equal from the metaphysical/natural perspective. These then stand in for "rich" and "poor." 3) The poor had nothing to loose but their liberty, and could not rationally have submitted that for any price. (As Locke's argument against Hobbes!) 4) Further, it's reasonable to believe that a thing was invented by those to whom it is useful rather than by those to whom it is harmful. Rousseau’s Conjectural History Rousseau’s Conjectural History Rousseau’s Conjectural History Rousseau’s Conjectural History Rousseau’s Conjectural History Rousseau’s Conjectural History