Epistemology: Knowledge, Skepticism, and Ignorance Clark Wolf Director of Bioethics

advertisement

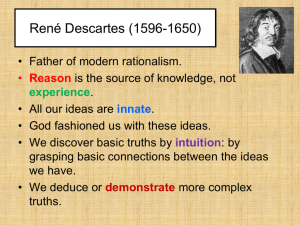

Epistemology: Knowledge, Skepticism, and Ignorance Clark Wolf Director of Bioethics Iowa State University jwcwolf@iastate.edu Mind and body are either the same thing, or they are different substances. If two things are identical, then they will have all the same properties. So if my mind and body are the same substance,they’ll have all properties in common. But I can doubt my body’s existence– my body is dubitable. I can’t doubt my mind’s existence– my mind is indubitable. Therefore mind and body are different substances. 1) Mind and body are either the same thing, or they are different substances. 2) If two things are identical, then they will have all the same properties. 3) So if my mind and body are the same substance,they’ll have all properties in common. 4) But I can doubt my body’s existence– my body is dubitable. 5) I can’t doubt my mind’s existence– my mind is indubitable. 6) Mind and body do not have all properties in common. 7) Therefore mind and body are different substances. Argument for Analysis Argument for Analysis I have an idea of a perfect being: a being that is perfect in every way. This idea is itself perfect. But I’m imperfect– I clearly have failures and faults and limitations. As an imperfect being, I couldn’t be the source, origin, or cause of something perfect: only something perfect could be the cause of something perfect. So there must be a perfect being external to me which is the cause of my perfect idea. Argument for Analysis 1) I have an idea of a perfect being: a being that is perfect in every way. 2) This idea is itself perfect. 3) But I’m imperfect. (I clearly have failures and faults and limitations.) 4) As an imperfect being, I couldn’t be the source, origin, or cause of something perfect: only something perfect could be the cause of something perfect. 5) So there must be a perfect being external to me which is the cause of my perfect idea. Argument for Analysis: According to Descartes, we can’t know something unless we are so absolutely certain that it is true that we can’t doubt it. But if we accepted this, we would be forced to conclude that we know nothing at all, or almost nothing. It’s just wrong to say that we don’t know something just because we can doubt that it’s true, or just because it’s possible that it’s false: this isn’t what we mean by the term ‘know.’ For example, when I say “I know where I parked my bike, because I remember doing it.” I don’t mean to indicate that I can’t possibly be wrong about where I parked my bike, even if it turns out that I’m a brain in a vat. So to know something isn’t to be certain about it. So the Cartesian analysis of knowledge doesn’t capture what we typically mean by ‘knowledge.’ Argument for Analysis: 1) According to Descartes, we can’t know something unless we are so absolutely certain that it is true that we can’t doubt it. 2) But if we accepted this, we would be forced to conclude that we know nothing at all, or almost nothing. 3) But we know more than the Cartesian view would support. 4) So to know something isn’t to be certain about it. 5) Descartes was wrong to believe that certainty is necessary for knowledge. Argument for Analysis: You don’t know something unless you are absolutely certain that it is true, and you have good reasons for your belief that constitute evidence that your belief is true. You believe that you are in a classroom in Ames Iowa. But if you think carefully about it, you don’t know that you’re in a classroom in Ames Iowa. For example, you might instead be a brain in a vat in some laboratory somewhere, being fed false impressions of your surroundings and your situation. You have no evidence that you are not a brain in a vat. So you cannot be certain that you are in a classroom in Ames Iowa. Argument for Analysis: 1) You believe that you are in a classroom in Ames Iowa. 2) It is possible that you are a brain in a vat in some laboratory somewhere, being fed false impressions of your surroundings and your situation. 3) You have no evidence that you are not a brain in a vat. 4) You don’t know something unless you are absolutely certain that it is true, and you have good reasons for your belief that constitute evidence that your belief is true. 5) So you cannot be certain that you are in a classroom in Ames Iowa. 6) Therefore you don’t know that you’re in a classroom in Ames Iowa. Epistemology: Theory of Knowledge What is ‘knowledge?’ What is it to know something? What does it mean to say that a belief is ‘justified?’ What can we know? Knowledge and Belief We have a vast collection of beliefs, and some of them are false: -Some people believe that astrology can inform us about our futures. -Some people believe that aliens from outerspace are in contact with human beings. -Some people believe that human beings are the product of natural selection and survival of the fittest. -Some people believe that there is a God who created everything and who cares about us. -Some people believe that human beings will make settlements on Mars before the end of the next millenium. -Some people believe that human beings are more likely, in the next millenium, to deplete the earth of its resources and destroy the ecosystems on which we depend for our lives. Sifting and sorting: Those beliefs about which we're less certain are less likely to count as knowledge than those we're more certain of. Are there any beliefs of which we are absolutely certain? Knowledge and Belief We believe many things. Not all of the things we believe are things we know. Among the things I believe, which are the things I know? Knowledge and Belief Among the things I believe, which are the things I know? Hypothesis: The things I know are the beliefs that are true. Problem: What if I have true beliefs by accident or for bad reasons? Knowledge and Belief Example: Accidentally True Belief. I’ve been brainwashed to believe that I’m a philosophy professor. My reason for believing this is that I’ve been brainwashed, so I’d believe it whether or not it was true. But it happens to be true. Knowledge and Belief Example: I have on my car a sticker that says "Oberlin College." People who see this sticker often form the belief that I graduated from Oberlin college. BUT: The sticker was on the car when I bought it (used), and I didn't put it there. If people knew this, it would undermine their belief that I went to Oberlin college, by showing that their reason for believing that I did was not a good reason. Question: If you don't know that the sticker was on my car when I bought it, is your belief that I went to Oberlin College justified? Knowledge: Platos’s Analysis Plato, Euthyphro: Knowledge is Justified True Belief. A person S knows a proposition P If and only if: 1) S believes P 2) S is is justified in believing P 3) P is true Knowledge: Platos’s Analysis A person S knows a proposition P If and only if: 1) S believes P 2) S is is justified in believing P 3) P is true What is belief? (Mental attitude associated with accompanying dispositions) What are the objects of belief? (Propositions: Statements that can be true or false.) When is belief justified? (Alternate theories of justification) What is it for a proposition to be true? (Alternate theories of truth) Knowledge: Platos’s Analysis JUSTIFICATION AND BELIEF: The 'Why?' game...: at a certain point in a childs development, she gets the idea that there are reasons for things, and start asking why. Justification: A theory of the justification of beliefs must provide us with a model of how to play the why game, or as it is sometimes called, the justification game. Example: Proposition P: We are in a classroom together in Ames Iowa. [Presumably we all believe that P is true.] Knowledge and Belief: Descartes’s Problem Descartes's Problem: How can I have knowledge of anything, and which are the things I know? Sifting and sorting: Those beliefs about which we're less certain are less likely to count as knowledge than those we're more certain of. Are there any beliefs we're absolutely certain of? Knowledge and Belief: Descartes’s Problem DF of "undermining:" A proposition P undermines another proposition Q just in case the truth of P would be good evidence either (i) that Q is false, or (ii) that our reasons for believing Q are not good reasons for believing Q. Proposed Principle for Negative Justification: Take any propositions P and Q where P undermines Q. If you have no evidence that P is false, then you are not fully justified in believing Q. Knowledge and Belief: Descartes’s Problem Example 1: I have on my car a sticker that says "Oberlin College." People who see this sticker usually form the belief that I graduated from Oberlin college. BUT: The sticker was on the car when I bought it (used), and I didn't put it there. If people knew this, it would undermine their belief that I went to Oberlin college, by showing that their reason for believing that I did was not a good reason. Question: If you don't know that the sticker was on my car when I bought it, is your belief that I went to Oberlin College justified? Knowledge and Belief: Descartes’s Problem Argument: 1) John regards the Oberlin sticker on Clark’s car as evidence that Clark went to Oberlin college. 2) John’s belief that <Clark went to Oberlin College> is based on the fact that he saw an Oberlin sticker on Clark’s car. 3) Contrary to John’s belief, the sticker on Clark’s car is not evidence that Clark went to Oberlin. 4) Therefore John’s belief that Clark went to Oberlin is not justified. 5) Therefore John does not ‘know’ that Clark went to Oberlin. Knowledge and Belief: Descartes’s Problem Descartes, Meditation I: The Dream Argument 1) In Meditation 1, Descartes believes that he is sitting before a fire. 2) But if Descartes is in bed dreaming, then he's not before a fire. 3) Descartes argues that he has no evidence (or inadequate evidence) to justify his belief that he's not dreaming. 4) So he doesn't know that he's not dreaming. 5) So he doesn't know that he's sitting before a fire. Skepticism: Skepticism: The view that we don’t have any knowledge. “Nobody knows anything. Not even me. I don’t even ‘know’ that nobody knows anything. But it’s true.” Two Skeptical Scenareos Sextus Empiricus' Trilemma (a Modern Rendition): (Answers to the "why" game.) 1) We have knowledge only if our beliefs are justified. 2) 'justification' can take three possibile forms: A) We justify our total belief set by reference to some foundational belief or set of such beliefs, which are not themselves justified by any further beliefs. B) Our beliefs mutually justify one another. C) There is an endless regress of justifying reasons. 3) Not A: A foundational belief could not justify other beliefs unless it were itself justified. 4) Not B: Circular justification is no justification at all. 5) Not C: An endless regress of reasons could not provide justification for our first-level beliefs. 6) Therefore, we don't have knowledge. [Sextus was a skeptic.] Skeptical Question: Do we know anything at all? If I might be dreaming, might be a brain in a vat, might be systematically deceived by an evil genius… …then can I know anything? Many epistemic theories are attempts to show that skepticism is false, and that we can have justified beliefs in spite of the force of skeptical arguments. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Meditation One: Introduces Skeptical Problem, Method of Doubt, distinguishes among different sources of belief. The Project: Wholesale reconstruction of a belief system: Descartes wants to tear it to the ground and build it back from solid foundations. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy THE SKEPTICAL PROBLEM: The starting point: recognition that many previously held beliefs are either false or unfounded. We need, he believes, a firm foundation on which to place our knowledge, to insure that our beliefs will be true. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Method of Doubt: Test beliefs according to their "doubtability." If I can doubt one belief, but I cannot doubt another, then surely my belief in the second is firmer than my belief in the first. For the moment, Descartes recommends that I admit only those truths (if any) which I can immediately perceive clearly and distinctly. Any others whose truth I can derive from this basic set will also be justified. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy First Possible Way Out: Foundationalism: A person is justified in holding a belief only if it is either self evident, or is directly or indirectly inferred from self evident propositions by selfevident principles of inference. A proposition is self evident(df) just in case believing that it is true is sufficient for knowing that it is true. [Some philosophers have doubted that there are any self evident propositions.] DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Two Potential Problems for Foundationalism: [These two are inconsistent with one another. Do you see why?] 1) Perhaps there are no self-evident propositions. 2) Perhaps there are some self-evident propositions, but they are inadequate since they provide us with no conclusive argument against the skeptic. DESCARTES: Meditations CATEGORIES OF BELIEFS: Rather than examining each belief in turn, (there are just too many) Descartes categorizes his beliefs: 1) Blfs deriving from the senses. (Undermined by Dream argument) (But the images composing my dream must have their source somewhere-- there must exist some basic source of this material I dream about... no? But what that basic source may be is quite mysterious. Do I know that it mightn't be me?) 2) Blfs about empirical science have the same status as other blfs deriving from the senses. 3) Blfs about "simple and universal" things (math & Logic) Descartes finds that he can even doubt these...(Perhaps I get confused whenever I add 2 and 2) (139.2) DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy ON THE EVIL GENIUS HYPOTHESIS: Don't misunderstand: Descartes doesn't believe that there is an evil demon, he rather considers whether he has any evidence which would enable him to prove that there is not one. The evil demon hypothesis is one way to call into question the justification of beliefs which derive from the senses: it is a potential defeater for many of the things we think we know. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Meditation One ends as it starts: with unresolved doubts. It seems, at the end, that the demon hypothesis provides a potential reason for doubting just about anything. However, Descartes (like Hume later) finds that he cannot maintain skepticism: See p. 63: "But this undertaking is arduous and a certain laziness brings me back to my customary way of living." DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy One Kind of Objection: We don't have the technology to envat people, and there isn't an evil genius... In sum, the evil demon hypothesis is just not true. Response: This objection is a non-starter since it begs the question. Descartes never claimed that there is an evil genius (nor did I claim that we are really envatted brains). The point is to sift among our beliefs to find those that are more securely justified than others. The evil demon hypothesis is not true, but it is conceptually possible (That is, thinking about it doesn't involve us in any contradictions.) DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Descartes and Skepticism: if we can find a foundation for our belief system which is both 1) self evidently true, and 2) sufficiently powerful to enable us to deduce that our perceptual beliefs are true, THEN we could escape the skeptical argument. Is there such a foundation? DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy ON TO MEDITATION TWO! Descartes DISCOVERS a self-evident belief. Descartes ARGUES that some of his beliefs could not have originated with him. Descartes PROVES (?) that God exists and that God is not a deceiver. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Cogito: Consider the proposition 'I exist.' Apply method of doubt: If there is any conceivable circumstance in which it could SEEM TO ME that I exist, and yet I could be wrong, then the proposition 'I exist' can be doubted. Is there such a circumstance? Demon world is the most complete hallucination imaginable. If I couldn't be wrong in the demon world, then I couldn't be wrong at all. But in the demon world I must exist, since there is an 'I' to be deceived. Therefore I know that I exist any time I stop to consider the question. "Cogito Ergo Sum." (I think therefore I am.) DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Descartes’s Foundational Belief: “I exist.” 1) I know X only if I perceive that clearly and distinctly that X is true, such that it is impossible for me to doubt X. 2) Query: Can I doubt my own existence. 3) For me to doubt my existence, there must be a ‘me’ to do the doubting. 4) Any time I doubt my existence, I can clearly and distinctly understand that I must exist. 5) I can’t doubt my own existence. 6) I know the proposition “I exist.” DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy "Cogito Ergo Sum." (I think therefore I am.) How far will this get us? Descartes has argued that the proposition "I exist." is self evident. But is it powerful enough that it can support my knowledge of the external world? Can this help me out of the vat? DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Descartes and Skepticism: if we can find a foundation for our belief system which is both 1) self evidently true, and 2) sufficiently powerful to enable us to deduce that our perceptual beliefs are true, THEN we could escape the skeptical argument. Is there such a foundation? DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy "Cogito Ergo Sum." (I think therefore I am.) How far will this get us? Descartes has argued that the proposition "I exist." is self evident. But is it powerful enough that it can support my knowledge of the external world? Can this help me out of the vat? Question: What is this thing (ME) whom we know to exist? Am I my body? Not in the demon world, where I still exist... I am a thing that thinks. That's all I know for sure. I am something that doubts, affirms, understands, denies, wills, refuses, imagines and senses. In fact, what I know is that I am a thing that has IDEAS! What are ideas? DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy The Wax Example: My idea of the wax remains the same while the wax goes through drastic changes: it is the same wax although its properties change when it is melted or frozen. My senses do not give me an understanding of the wax: I get different sensory information as the wax changes, but my idea of the wax itself persists over these changes. So "perceiving the wax" is essentially an act of the mind, not of the senses. Theory of Representative Ideas: Knowledge is a two-way relationship between one's ideas and the objects in the external world. We have internal access to our ideas, but not to the objects of which they are ideas. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy The Wax Example: My idea of the wax remains the same while the wax goes through drastic changes: it is the same wax although its properties change when it is melted or frozen. My senses do not give me an understanding of the wax: I get different sensory information as the wax changes, but my idea of the wax itself persists over these changes. So "perceiving the wax" is essentially an act of the mind, not of the senses. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Theory of Representative Ideas: Knowledge is a two-way relationship between one's ideas and the objects in the external world. We have internal access to our ideas, but not to the objects of which they are ideas. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy A Problem for Cartesian Foundationalism: The theory of representative ideas leaves us trapped in the confines of our own mind! Descartes has (perhaps?) found a foundational belief, but is it powerful enough to respond to the skeptic? Does it enable us to think ourselves out of the vat? Unfortunately, even if we have certainty with respect to the COGITO and also to our first level sensory beliefs (beliefs about the way things seem to us), we cannot derive from these basic beliefs any statements about the existence of external objects. We can't make it out of the vat. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy To respond to the skeptic, a foundationalist must show two things: 1) There are self evident propositions, and 2) From these propositions we can derive knowledge of empirical reality. So Descartes needs some more equipment: He needs GOD. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy MEDITATION THREE: Concerning the Existence of God Method: Descartes has established that he exists as a thinking thing. In the third meditation he undertakes to examine the ideas that he finds in his mind, and to consider their origin. (@38+) "But here I must inquire particularly into those ideas that I believe to be derived from things existing outside of me." If he can deduce that these ideas do nor originate in him, then he may conclude that there is something external that is the origin of these ideas. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy DESCARTES ARGUMENTS CONCERNING THE EXISTENCE OF GOD: Argument from the Perfect Idea of an Infinite Being: 1) I have an idea of God which is the idea of a substance that is infinite, independent, supremely intelligent, and supremely powerful. [III.45-6] 2) As a finite and imperfect being, I cannot be the cause of a perfect idea of an infinite substance. [III.45-6] 3) Only an infinite and perfect being could be the cause of such an idea. 4) Therefore, there exists an infinite and perfect being who is the cause of my idea. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Ontological Argument: (Meditation Five) 1) I have an idea of God. 2) The idea of God is the idea of a being that has all perfections. 3) 'Existence' is a perfection. [That is, what exists in reality is more perfect than what exists only in the imagination.] 4) Therefore a being that has all perfections must have 'existence.' 5) God exists. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Anselm's Version of the Ontological Argument: 1) I have an idea of God. 2) The idea of God is the idea of the greatest conceivable being. 3) A being that exists in reality as well as in the mind (in imagination) is greater than a being that exists only in the mind. 4) Suppose that the Greatest Conceivable Being exists only in the mind but not in reality. 5) Then we can conceive of a being that is even greater: one who exists in reality as well as in the mind. 6) Then we can conceive of a being greater than the greatest conceivable being-- but that would be a contradiction! 7) Therefore it is not the case that the greatest conceivable being exists only in the mind but not in reality. 8) Therefore the greatest conceivable being exists in reality as well as in the mind. 9) Therefore God exists. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Some Further Steps: 1) If there is a perfect being, then the evil demon hypothesis is false. 2) Therefore my senses give me true information about the world. 3) Therefore skepticism is false. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Physicalism: Mind and body are both physical substances, and the consequence of interaction of physical particles and forces. Dualism: Mind and body are different substances that interact but which are essentially different. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Mind and Body: Descartes is a Dualist: he argues that mind and body are different, separate substances. Here is one Cartesian argument for Dualism: 1) If one substance has a property P while another substance lacks property P, then the two substances are not identical. 2) I can doubt the existence of my mind: my mind has the property of 'dubitability'. 3) I can't doubt the existence of my body: my body lacks the property of dubitability. 4) Therefore my mind is a different substance from my body. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Reservation: is 'dubitability' a property of things or of thinkers? Perhaps premises two and three say more about Descartes thought processes than about the things Descartes is considering. For Physicalism: Physical Evidence of Anasthesia Contemporary Science of Consciousness presumes physicalism. Mind-Brain Identity and “Split Brain” cases. DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy Final Issues in Cartesian Epistemology: Does Descartes have a satisfactory response to the skeptic? Unless one is satisfied with the proof of the existence of God, one may conclude that Descartes has escaped the skeptical conclusion only because he accepted a bad argument. Few believe that any of the philosophical arguments for God's existence is conclusive; indeed James assumes that his listeners and readers will already have recognized that the evidence for the existence of God is inconclusive. Descartes: Where from here…? Does Descartes have a satisfactory response to the skeptic? Unless one is satisfied with the proof of the existence of God, one may conclude that Descart has escaped the skeptical conclusion only because he accepted a bad argument. Few believe that any of the philosophical arguments for God's existence is conclusive; indeed James assumes that his listeners and readers will already have recognized that the evidence for the existence of God is inconclusive. If this is right, where does it leave Descartes? Are we still in the vat? Some people conclude that Descartes simply failed to provide a convincing response to the skeptic. The meditations get the epistemological project off the ground, but don't really take it beyond the vat. Where does the argument go wrong? There are several possibilities: Descartes: Where from here…? Conclusions from Descartes Discussion: 1) The negative principle of justification may just be too strong a condition to place on knowledge. Perhaps this principle should be rejected. [Many (most!) contemporary epistemologists would reject it.] 2) Some attribute Descartes failure to the representative theory of ideas: Bertrand Russell argued that perception gives us immediate contact with the world, and denies Descartes claim that we are only in immediate contact with our ideas. 3) Some argue that Descartes' failure shows that foundationalism is unacceptable. One might opt instead for a Coherentist or Pragmatist account of the justification of belief. [James' opts for a pragmatist solution. Other contemporary epistemologists hold that beliefs come in systems and deny that it is circular for all beliefs to be justified by reference to other fallible beliefs. Descartes: Where from here…? Some Non-Cartesian Alternatives: Coherentism: There are no adequate foundations for knowledge, but we can be justified in our beliefs provided that they cohere appropriately with other of our beliefs. [Coherentists must then give a clear account of what 'coherence' means, and must respond to the objection that fiction may be coherent. See Keith Lehrer Theory of Knowledge for a clear, contemporary coherentist account of justification.] Fallibilism: To know a proposition, it not necessary to have indubitable certainty that it is true. Most fallibilists would reject the Negative Principle of Justification. Most contemporary epistemologists are fallibilists. Those epistemologists who are not fallibilists are mostly skeptics. [I haven't done a survey, these are my impressions.] Next: William James’s Will to Believe James addresses a different problem: The problem of rational belief. James’s question is whether it is every rationally permissible to believe something when there is a dearth of evidence for it. James takes it for granted that evidence for the existence of God is insufficient to make belief a requirement of rationality, but argues for the weaker claim that belief is permissible– that is, that disbelief is not a requirement of rationality. Pascal's Wager: "Either God is, or He is not. But to which view shall we be inclined? Reason cannot decide this question. Infinite chaos separates us. At the far end of this infinite distance a coin is being spun which will come down heads or tails. How will you wager?” Next: William James’s Will to Believe Some Jamesian Terms: hypothesis, Live hypothesis, Dead hypothesis, Option, Forced option Avoidable option, Momentus option Trivial option. Genuine Option: Living, forced, and momentus. Next: William James’s Will to Believe Doxastic Voluntarism: The theory that belief can be commanded by the will: we can aquire a belief that P (for example, a belief that God exists) simply by willing to believe that P. Question: Is James committed to doxastic voluntarism? Is Pascal? [The answer is no but you need to be able to explain why not!] Next: William James’s Will to Believe Principles of [Dis]Belief: 1) If there is inadequate evidence that P is true, then it is irrational to believe P. [Clifford, Huxley] 2) James: Under certain circumstances, we may be justified in believing P even if there is inadequate evidence that P is true. Next: William James’s Will to Believe "Our passional nature not only lawfully may, but must, decide an option between propositions, whenever it is a genuine option that cannot by its nature be decided on intellectual grounds; for to say, under such circumstances, "Don't decide, but leave the question open," is itself a passional decision, - just like deciding yes or no, -- and is attended with the same risk of losing the truth." James Next: William James’s Will to Believe James View: Sometimes we must believe even where the evidence is inadequate. We have two epistemic goals: (i) Gain truth, and (ii) Avoid falsehood. It is only because we have both aims that our epistemic situation is interesting: If we simply wanted to gain truth, we could believe everything. If we only wanted to avoid falsehood, we could believe nothing. But given that we have both aims, James concludes that "a rule which would absolutely prevent me from acknowledging certain kinds of truth if those kinds of truth were really there, would be an irrational rule. Next: William James’s Will to Believe The "Religious Hypothesis: Is the option to believe in God live? Forced? Momentus? “We stand on a mountain pass in the midst of whirling snow and blinding mist, through which we get glimpses now and then of paths which may be deceptive. If we stand still we shall be frozen to death. If we take the wrong road we shall be dashed to pieces. We do not certainly know whether there is any right one. What must we do? ‘Be strong and of a good courage. Act for the best, hope for the best, and take what comes. . . . If death ends all, we cannot meet death better.’” --James Next: William James’s Will to Believe Next: William James’s Will to Believe Next: William James’s Will to Believe