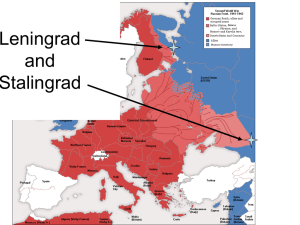

HOUSING IN LENINGRAD:

advertisement