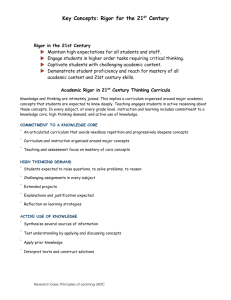

T R A N S I T I O N... F O R 2 1 S T C E N... P U B L I C S C H O... State Board of Education | Department of Public Instruction

advertisement