LAST BEST CHANCE 2004 TASK FORCE REPORT MIDDLE GRADES

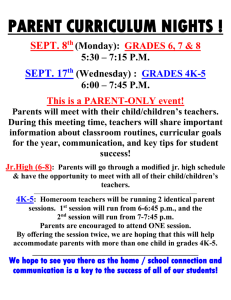

advertisement