‘savoir’ of ‘connaissance’

advertisement

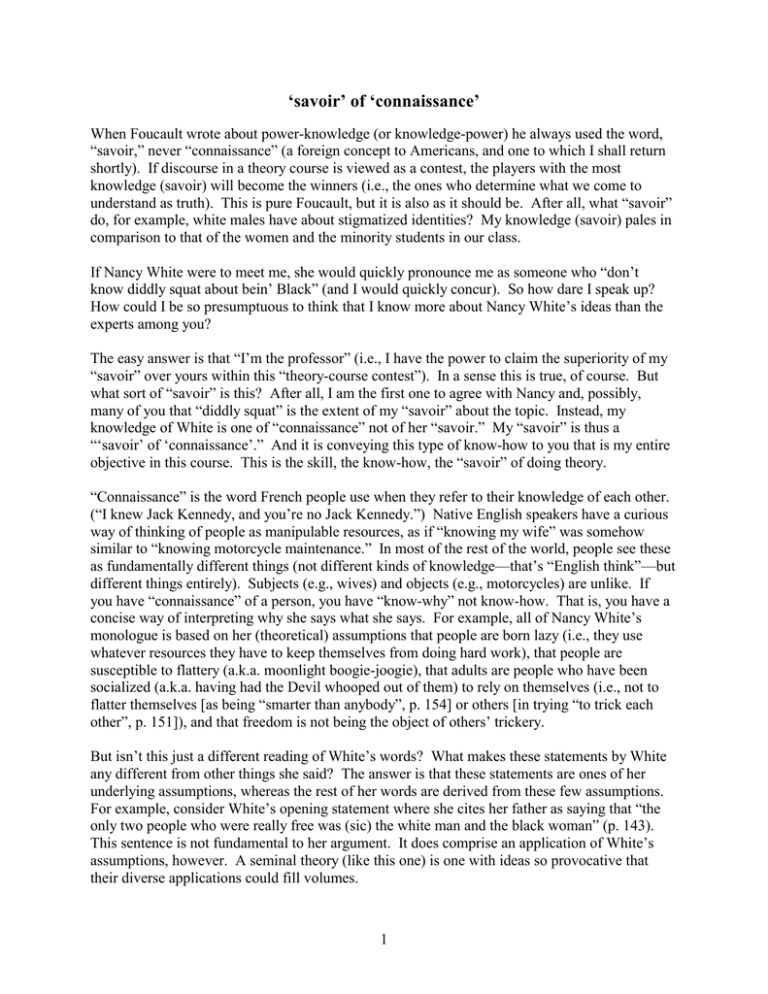

‘savoir’ of ‘connaissance’ When Foucault wrote about power-knowledge (or knowledge-power) he always used the word, “savoir,” never “connaissance” (a foreign concept to Americans, and one to which I shall return shortly). If discourse in a theory course is viewed as a contest, the players with the most knowledge (savoir) will become the winners (i.e., the ones who determine what we come to understand as truth). This is pure Foucault, but it is also as it should be. After all, what “savoir” do, for example, white males have about stigmatized identities? My knowledge (savoir) pales in comparison to that of the women and the minority students in our class. If Nancy White were to meet me, she would quickly pronounce me as someone who “don’t know diddly squat about bein’ Black” (and I would quickly concur). So how dare I speak up? How could I be so presumptuous to think that I know more about Nancy White’s ideas than the experts among you? The easy answer is that “I’m the professor” (i.e., I have the power to claim the superiority of my “savoir” over yours within this “theory-course contest”). In a sense this is true, of course. But what sort of “savoir” is this? After all, I am the first one to agree with Nancy and, possibly, many of you that “diddly squat” is the extent of my “savoir” about the topic. Instead, my knowledge of White is one of “connaissance” not of her “savoir.” My “savoir” is thus a “‘savoir’ of ‘connaissance’.” And it is conveying this type of know-how to you that is my entire objective in this course. This is the skill, the know-how, the “savoir” of doing theory. “Connaissance” is the word French people use when they refer to their knowledge of each other. (“I knew Jack Kennedy, and you’re no Jack Kennedy.”) Native English speakers have a curious way of thinking of people as manipulable resources, as if “knowing my wife” was somehow similar to “knowing motorcycle maintenance.” In most of the rest of the world, people see these as fundamentally different things (not different kinds of knowledge—that’s “English think”—but different things entirely). Subjects (e.g., wives) and objects (e.g., motorcycles) are unlike. If you have “connaissance” of a person, you have “know-why” not know-how. That is, you have a concise way of interpreting why she says what she says. For example, all of Nancy White’s monologue is based on her (theoretical) assumptions that people are born lazy (i.e., they use whatever resources they have to keep themselves from doing hard work), that people are susceptible to flattery (a.k.a. moonlight boogie-joogie), that adults are people who have been socialized (a.k.a. having had the Devil whooped out of them) to rely on themselves (i.e., not to flatter themselves [as being “smarter than anybody”, p. 154] or others [in trying “to trick each other”, p. 151]), and that freedom is not being the object of others’ trickery. But isn’t this just a different reading of White’s words? What makes these statements by White any different from other things she said? The answer is that these statements are ones of her underlying assumptions, whereas the rest of her words are derived from these few assumptions. For example, consider White’s opening statement where she cites her father as saying that “the only two people who were really free was (sic) the white man and the black woman” (p. 143). This sentence is not fundamental to her argument. It does comprise an application of White’s assumptions, however. A seminal theory (like this one) is one with ideas so provocative that their diverse applications could fill volumes. 1 OK, so what is a theory? A theory is a set of assumptions—the ideas of which all a theorists’ other words comprise mere applications. Postmodernists refer to theories as “metalanguages.” As Derrida argued, connaissance of a theory is knowledge of its grammar (just like knowing one’s wife is knowing the principles that guide her behavior). It is not sufficient merely to be able to “talk the talk” (i.e., to speak the theorist’s metalanguage). This is why I always curtail our discourse about theories when they “go off on applied tangents.” Our task is to make theorists’ assumptions explicit, to specify their grammars. How can I tell the difference between an application of theoretical premises (or assumptions) and the premises themselves? The ability to answer this question is “the skill” that I shall talk about again and again this semester. Let’s return to my assertion that “only white men and black women are free” is an application but not an assumption of White’s theory. You can tell an application from a premise in that the former follows from the latter, but not the reverse. In this case, the above statement can clearly be seen to follow logically from the following premises: 1) White men try to trick others. 2) Black women are immune to trickery. 3) Freedom is “not being the object of trickery.” There is no way that you can deduce these premises from the statement that “only white men and black women are free.” The three premises comprise (part of) a theory; the statement does not. This is not merely a question of different readings of a text; it is a matter of digging deep into authors’ theoretical articulations, and pulling out those key premises from which everything else that they write can be generated. Only once you have made these premises explicit can you legitimately claim “connaissance” of a theorist. Mere know-how doesn’t comprise understanding. Social theories explain why behavior occurs; doing theory requires know-how about making others’ premises explicit. As the semester proceeds, we still have many opportunities to develop your “‘savoir’ of ‘connaissance’.” Yet, it is important that you be able to distinguish it from other types of “savoir.” Allow me to venture a theory—a modification of Nancy White’s: Every social field defines a set of legitimate moves. “Savoir” within a field corresponds to one’s mastery over these moves. “Savoir” is thus field-specific, and when “savoir” from one field is introduced into another, this is “moonlight boogie-juggie” (MBJ, for short). Novices are players in social fields who have difficulty distinguishing among various varieties of “savoir.” But novices have two types of knowledge that they can develop at this point—a mastery of moves within a single playing field (savoir) and a mastery at recognizing the set of moves that is legitimate within their current playing field (savoir of connaissance). If they lack the former type of knowledge, they are doomed to lose; if they lack the latter, they are doomed to be mystified by MBJ. And so I hope that you can now see that my objective during the course of this semester is that you become immunized from MBJ. A first step in this direction is that you learn to distinguish legitimate versus nonlegitimate moves in our “theorizing game.” To the extent that your objective is to play a particular theoretical game (i.e., to apply a specific theory), you will find 2 yourself making nonlegitimate moves in our game. (Although we can never be certain of each others’ objectives, you will note that such awareness does require mutual “connaissance.”) This is not to say that there is something illegitimate about making these moves. Surely applying theories helps us verify among ourselves that we understand a theory’s premises correctly. However, what should not be lost in our “playing with theorists’ premises” is our ongoing awareness that these illustrations are only moves toward making these premises explicit. That is, we are ongoingly aware of the danger of changing our social field from “a theorizing game” to “a specific theorist’s game.” Thus we are all umpires as well as players in our theorizing game. As players we share the common objective of gaining “the skill” of finding premises among applications. But at the same time we are umpires who never forget that playing each theorist’s game requires an “application skill” specific to that theory—a skill that is other than (although surely related to) the skill we are developing. As umpires we always keep in mind that this other type of “savoir” is something secondary to our game. Once sharpened, our skills as umpires will restrain our bedazzlement with any one theorist’s game, so that we are not tempted to believe that the theorist’s assumptions are better than all others. Within our theorizing game wouldn’t accepting such a belief merely be an acknowledgement that we have succumb to the theorist’s moonlight boogie-joogie? 3