Document 10683877

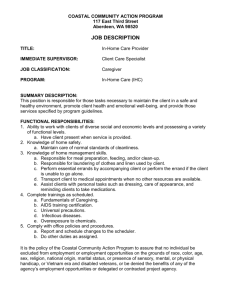

advertisement