A STUDY JONATHAN TECHNOLOGY (

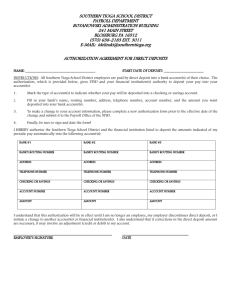

advertisement