Toward understanding new feature request systems as

advertisement

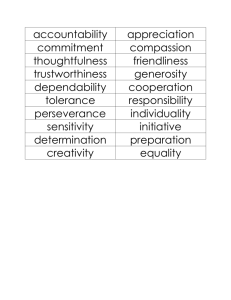

Toward understanding new feature request systems as participation architectures for supporting open innovation Michelle W. Purcell College of Computing & Informatics Drexel University 3141 Chestnut St., Philadelphia PA 610-864-1060 E-mail: mjw23@drexel.edu ABSTRACT Most research regarding innovation in open source software communities pertains to identifying supporting conditions for promoting code contribution as a way to innovate the software. Instead, this paper seeks to identify social and technological affordances of new feature request systems and their potential to support open innovation through integration of peripheral community members’ ideas for advancing the software. Initial findings from the first of a planned study of multiple open source software communities are presented to identify attributes of effective participation architectures. Categories and Subject Descriptors H.5.3 [Information Interfaces and Presentation]: Group and Organization Interfaces – collaborative computing, computersupported cooperative work, organizational design. General Terms Design, Management Keywords Open innovation, Free and open source software, Participation architectures, Organizational studies. 1. INTRODUCTION New feature request systems in Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) projects provide a key method for users to request community developers to make changes to the software. The extent to which new feature requests enable users to represent and generate support for their ideas has implications for project sustainability and open innovation. Much has been written about the coordination of work among distributed developers in FOSS projects [2, 5–7]. The process is well established, relying on code modularity to reduce coordination needs among developers and tools such as the mailing list, bug reporting tools, IRC and code repositories to maintain awareness and provide group transactive memory. These characteristics enable developers to heedfully interrelate [15] while working on selected portions of the code Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from Permissions@acm.org. OpenSym '15, August 19 - 21, 2015, San Francisco, CA, USA © 2015 ACM. ISBN 978-1-4503-3666-6/15/08…$15.00 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2788993.2789842 base largely independently to produce a major code release. However, little is known about how to support heedful interrelating between outsiders and (mainly technical) community members during the process of requesting community developers to make enhancements to the software. 2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND 2.1 Models of Open Innovation Gassmann & Enkel [4] provide three models describing how knowledge flows within open innovation. Inside-out innovation applies when ideas developed internally to the firm are made innovative through the externalization of that knowledge and sale of Intellectual Property (IP). Outside-in innovation occurs when firms’ integrate knowledge from suppliers and customers. A coupled process combines both outside-in and inside-out forms of innovation. Spaeth et al. [14] use the term “push model” to describe a variant of outside-in innovation that derives from unsolicited knowledge sharing by stakeholders outside the firm. For example, in IBM’s open sourcing of the Eclipse integrated development environment, code contributions from outside contributors provided key software innovations [14]. Push models of open innovation in open source software have focused on contingencies supporting code contributions, such as the role of the development process [12, 18]; project governance structures [13, 17]; software architecture [1, 9], or business strategy [16]. This study takes a different perspective, investigating a push model of open innovation via new feature requests from persons requesting community developers to make enhancements to the software. Participant architectures are “the socio-technical framework that extends participation opportunities to external parties and integrates contributions” [17, p. 146]. They enable varying degrees of openness which in turn are positively related to sustaining and growing an innovation community [17]. This paper presents preliminary findings pertaining to the research question: Can we identity technological affordances of participation architectures that support a community of innovation, given that this requires the participation by outsiders in an existing system of heedful interrelating between (mainly technical) community members? 2.2 Heedful Interrelating in Open Innovation Designing a participant architecture to support open innovation must address the challenge that in diverse communities, knowledge is ‘stretched across’ participants, rather than shared between them [8]. Therefore, it must facilitate the process of distributed cognition. Heedful interrelating as a lens enables a finer grained analysis of the distributed cognition process, a.k.a. collective mind, helping elucidate the conditions that support it. To heedfully interrelate to enact collective mind requires one heedfully represent and subordinate their contributions, “a heedful contribution enacts collective mind as it begins to converge with, supplement, assist, and become defined in relation to the imagined requirements of joint action presumed to flow from some social activity system” [15, p. 365]. Therefore, any participation architecture must consider factors that influence the ability to act heedfully to represent knowledge within the current state of the social activity. 2.3 Affordances Supporting Heedful Interrelating Majchrzak. et al. identity affordances of social media technology – “the action potential that can be taken given a technology” [10, p. 39] – that have the potential to support communal online knowledge sharing. These affordances are closely related to the roles and key practices of heedful interrelating shown in Table 1. Table 1. Mapping affordances of social media for online communal knowledge sharing to heedful interrelating Affordance [10] Metavoicing Triggered Attending Definition [10] Adding metaknowledge to the content that is already online. Metavoicing can take many forms including retweeting, voting on a posting, commenting on someone’s post, voting on a comment, “liking” a profile, etc. [p. 41] Engaging in the online knowledge conversation by remaining uninvolved in content production or the conversation until a timely automated alert informs the individual of a change to the specific content of interest [p.42]. Application to Heedful Interrelating Becoming aware of others’ participation in the community. Understanding when a task, debate, or decision requires your specific participation. NetworkInformed Associating Engaging in the online knowledge conversation informed by relational and content ties [p. 44]. Understanding whoknows-what so you can refer others to a knowledgeable source /collaborator. Generative Role-Taking Engaging in online knowledge conversation by enacting patterned actions and taking on community-sustaining roles in order to maintain a productive dialogue among participants [p. 45]. Adopting a specific role (e.g., facilitator or champion) or process to maintain dialogue among participants. Although designated for social media the definition is broad enough to be applicable to the new feature request process in FOSS which typically involves use of bug reporting tools and mailing lists for documenting and sharing knowledge related to a requests’ worthiness and technical feasibility. 2.4 Technology Affordances and Constraints Theory (TACT) Technology affordances and constraints theory [11] takes a nondeterministic approach to the study of technology. While technologies have features such as the ability to vote on an idea, that does not mean the feature will achieve the desired effect of gathering input from a wide variety of users. To understand the ability to achieve a desired outcome, one must look at the relationship between people and technology as it is this relationship that either affords or constrains an organization from achieving a desired goal. The method, data collection and analysis process for this study therefore examines affordances, constraints on action, and outcomes. 3. METHOD AND DATA COLLECTION Given the exploratory nature of this study a qualitative study using ethnographic methods was employed. The sample consists of one open source software project although the study of additional communities is planned. The project was chosen because there was evidence of users submitting new feature requests and the community welcoming new feature requests. The project employs a deployment business model meaning while the code is free users are willing to pay support, subscription, and professional services to maintain and customize the software [3]. The majority of development is done by paid developers at software companies and some of the institutions using the software. The project would be considered relatively small based on lines of code and users. Firstly, new feature requests submitted via the open community bug reporting web-platform were analyzed over several months. WIKI articles, and IRC and mailing-list communications were sampled – this analysis was related to the success or failure of new feature requests submitted via the web platform. This analysis permitted enculturation in community practices and allowed channels for user participation to be identified. Interviews were conducted with five core community members who were well-indoctrinated into community practice around the new feature request process. Four of the interviews were with user representatives and one was with a developer from a software company. Three of those interviewed were elected members of the governing board. Interviews were semi-structured lasting between 38 minutes and 1 hour and 10 minutes. Data were analyzed to identify how the technology afforded heedful interrelating as described in table 1. 4. FINDINGS As part of the process for submitting a new feature request participants are to propose their idea on the mailing list or IRC to identify whether it has already been discussed and is being worked on and gauge support for the idea. The mailing list and IRC are primarily text-based. While it is recommended to address the request to the mailing list or IRC first, one may submit the idea directly to the bug tracker for inclusion on the wishlist by setting it as wishlist importance themselves or another community member does it. The wishlist is hosted on Launchpad which is also primarily text-based. In this system items are designated an importance, status, assignee, and milestone. Additional metadata is captured such as the reporter, number, title, last update and heat. Users can comment on an item, increase the heat by stating whether it affects them, add attachments, tag it, or choose to subscribe to the item. Analysis showed that the participation architecture needed to support two processes for a new feature to be implemented, gaining support and identifying resources to implement. There were five factors related to generating support: affects a community member’s institution; overall effect on the community; effect on maintainability of software; social capital of the requester; knowledge availability to flesh out request. There were six factors related to obtaining resources for implementation: relates to a developer’s existing work; relates to a developer’s skill set; opportunity to build a developer’s reputation in community; opportunity to build a developer’s resume; time available; funding to support development. Broadly speaking, two types of new feature requests could eventually be implemented using the new feature request system, small and large requests, and the methods for getting a request implemented varied. Although large feature requests typically involved obtaining funding from one’s institution or convincing other institutions to pool funding to contract to a software support company to implement the request, smaller requests could happen in a number of ways. In the case of small requests, sometimes identifying resources was all that was necessary -- and a little serendipity. For example, one respondent described a fortunate circumstance of having a small change implemented after talking to developers on IRC: I brought up hey, wouldn’t it be great if, like I was thinking I was going to try and add this feature that I think my users would like. Does it make sense to you developers? This was in the IRC channel and then like “oh, we don’t have that little bit of data display, hold on. Oh yeah, here’s the code, now it displays.” In another case, generating support and identify resources was done by calling in favors: Going behind the scenes and working to get things done on a favor basis that happens a fair bit and it is usually for fairly small things. I have some good friends among the developers in the community. I’ve actually gotten them to work on a number of things for me over the years. One respondent described the Launchpad tool as providing means for generating support and identifying resources: So this is an expression at any place and time of some of the things that are going on in the community. Whether I am a developer looking at it trying to address some of those things and move the community along, or whether I am funder looking and it and I have some funding and yes that’s exactly what I want, here’s $5 and so on and so forth. While the Launchpad tool appeared to provide functionality related to generating support with the notion of heat and ability to provide comments, it did not seem a viable way to do that. One respondent said heat was not used in any formal way to assess importance of the requests and examination of the wishlist requests showed it as not being related to importance in implementing wishlist requests. Another respondent said she did not use Launchpad and communicated mainly through the mailing list because she did not feel she had the knowledge to participate in the technical discussions going on there. A number of feature requests in Launchpad sat in limbo for an extended period of time. When one respondent was asked why, his response was that the wishlist acts as “blue sky” and the most critical advancements will “bubble up to the surface.” However, another community member didn’t see it that way: And, institutions that put in a wishlist but don’t have funding associated with it to work on it is not terribly likely to ever happen. In my experience if somebody puts in a wishlist and has the funding to do it, it happens fairly quickly. All of this points to a lack of online communal knowledge sharing in the Launchpad tool regarding the two main functions of the participation architecture, generating support and identifying resources. 5. DISCUSSION The wishlist contained in the Launchpad tool did not support heedful interrelating well for generating support and identifying resources. There was not much online communal knowledge sharing and the notion of the tool supporting the ideas “bubbling up” did not occur often. This section presents examples of why in terms of the affordances for online communal knowledge sharing presented in Table 1. 5.1 Metavoicing While the wishlist had the technical feature of allowing tagging it was hit or miss as to its ability to organize items and maintain awareness of already requested features. One respondent said regarding tagging: Sometimes they are a convenient shortcut to see if something has already been filed. Unfortunately not everybody uses the tags consistently. On the other hand with regard to managing technical implementation the community had a well-established pattern of applying the “pull-request” tag when code needed to be added to the baseline for testing. 5.2 Triggered Attending Maintaining awareness of items on Launchpad items in order to provide feedback was mainly a manual process which involved reading the mailing list and IRC logs and subscribing to email updates and searching for items of interest. In discussing with a user representative how he knows when to provide feedback he said he signed up for email mailings for all bugs as triggered attending in terms of identifying specific items of interest was not adequately provided by the Launchpad tool: I read each one of them, yeah. Ultimately it’s part of my job to keep track of the software for my organization so I need to chime in where things may potentially affect us. 5.3 Networked Informed-Associating Identifying developer resources and generating support relies on finding out who knows what. One respondent when asked about how well the new feature request process worked said: For an organization considering the software or somebody who has been using the software but isn’t deeply tied into some of the existing communication channels or who doesn’t know some of the individuals who’ve spearheaded a development, rather who they are, my perception is that it could be much more of a challenge for them to figure out how to get started with, you know, with taking their idea and getting somebody to write the code for it, to write the documentation for it, and to get it folded it into the software. 5.4 Generative Role-Taking With regard to identifying resources, at times a wishlist item would sit in limbo with a developer assigned with little or no progress taken on implementing the feature. The community had no formal process for moving progress along on these items; one respondent described the process this way: And so it becomes in form a little of a creative approach, some of the networking within the community besides mailing list and IRC, so coming together at the annual conference, that sort of thing, provides an opportunity to get some of the stuck bugs unstruck, if you will. So, for the most part, all of that is quite informal. 6. CONCLUSION This paper presents an approach to analyzing how the technical affordances of a new feature request system afford or constrain participation by outsiders in an existing system of heedful interrelating between (mainly technical) community members. Examples were presented in terms of social media affordances to support online communal knowledge sharing. Preliminary findings suggest that the new feature request system does not support heedful interrelating during the two main tasks participants need to accomplish to have a new feature implemented which were generating support and identifying resources. This has implications for the new feature request system to enable open innovation as only those who can spend copious amounts of time monitoring and participating on the mailing list, IRC, and wishlist can hope to develop the connections within the community to generate support and identify resources necessary to have an idea implemented. The analysis presented here is a first step in a wider study that will also identify community roles and processes needed to support technology affordances. It will include multiple open source software communities with different business models for the dual purpose of: 1) aiming for a sample that achieves maximum variation and 2) considering the potential effect business model may have on instantiation of participation architectures. 7. REFERENCES [1] Baldwin, C.Y. and Clark, K.B. 2006. The Architecture of Participation: Does Code Architecture Mitigate Free Riding in the Open Source Development Model? Management Science. 52, 7 (2006), 1116–1127. [2] Bolici, F. et al. 2009. Coordination without discussion? Socio-technical congruence and Stigmergy in Free and Open Source Software projects. Socio-Technical Congruence Workshop in conj Intl Conf on Software Engineering, Vancouver, Canada (2009). [3] Chesbrough, H.W. and Appleyard, M.M. 2007. Open Innovation and Strategy. California Management Review. 50, 1 (2007), 57 – 76. [4] Gassmann, O. and Enkel, E. 2004. Towards a theory of open innovation: three core process archetypes. R&D management conference (2004). [5] Gutwin, C. et al. 2004. Group awareness in distributed software development. Proceedings of the 2004 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work (2004), 72–81. [6] Hemetsberger, A. and Reinhardt, C. 2006. Learning and Knowledge-building in Open-source Communities: A Social-experiential Approach. Management Learning. 37, 2 (2006), 187–214. [7] Howison, J. and Crowston, K. 2014. Collaboration through superposition: How the IT artifact as an object of collaboration affords technical interdependence without organizational interdependence. MIS Quarterly. 38, (2014), 29–50. [8] Lave, J. 1988. Cognition in practice: Mind, mathematics and culture in everyday life. Cambridge University Press. [9] MacCormack, A. et al. 2006. Exploring the Structure of Complex Software Designs: An Empirical Study of Open Source and Proprietary Code. Management Science. 52, 7 (2006), 1015–1030. [10] Majchrzak, A. et al. 2013. The Contradictory Influence of Social Media Affordances on Online Communal Knowledge Sharing. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication. 19, 1 (2013), 38–55. [11] Majchrzak, A. and Markus, M.L. 2012. Technology affordances and constraints in management information systems (MIS). Encyclopedia of Management Theory,(Ed: E. Kessler), Sage Publications. (2012). [12] Scacchi, W. 2002. Understanding the requirements for developing open source software systems. Software, IEE Proceedings- (2002), 24–39. [13] Shah, S.K. 2006. Motivation, Governance, and the Viability of Hybrid Forms in Open Source Software Development. Management Science. 52, 7 (2006), pp. 1000–1014. [14] Spaeth, S. et al. 2010. Enabling knowledge creation through outsiders: towards a push model of open innovation. International Journal of Technology Management. 52, 3 (2010), 411–431. [15] Weick, K.E. and Roberts, K.H. 1993. Collective mind in organizations: Heedful interrelating on flight decks. Administrative science quarterly. (1993), 357–381. [16] West, J. and Gallagher, S. 2006. Patterns of open innovation in open source software. Open Innovation: researching a new paradigm. 235, 11 (2006). [17] West, J. and O’Mahony, S. 2008. The role of participation architecture in growing sponsored open source communities. Industry and Innovation. 15, 2 (2008), 145–168. [18] Yamauchi, Y. et al. 2000. Collaboration with Lean Media: how open-source software succeeds. Proceedings of the 2000 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work (2000), 329–338.