Transitioning to A Lean Enterprise: A Guide for Leaders Volume III Roadmap Explorations

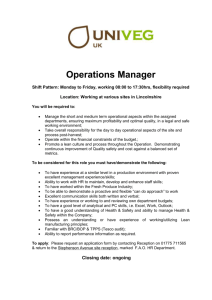

advertisement