SQUEEZED: WHY RISING EXPOSURE TO HEALTH CARE COSTS THREATENS THE HEALTH

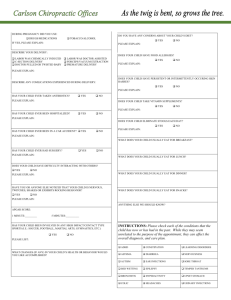

advertisement