by

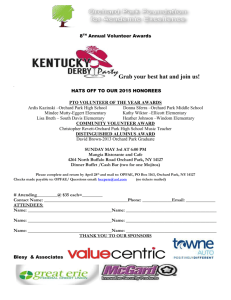

advertisement