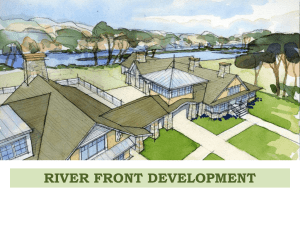

RE-USING DOWNTOWN WATERFRONTS A.

advertisement