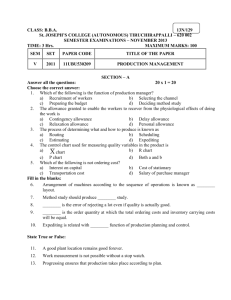

ROTCH~ RCj

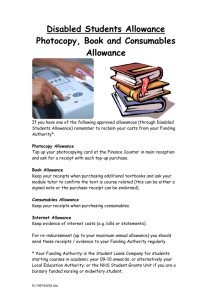

advertisement