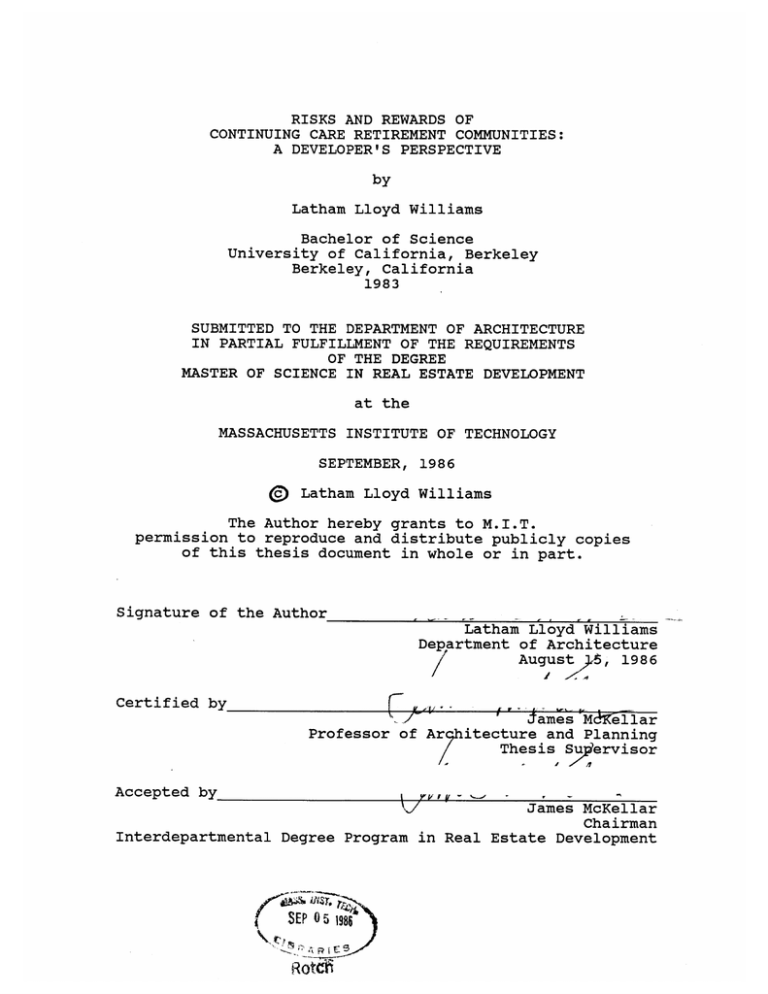

by Latham Lloyd Williams Bachelor of Science

advertisement