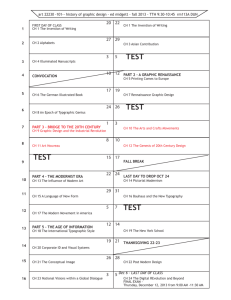

Use of Graphic Design Computer-Based Rule Systems

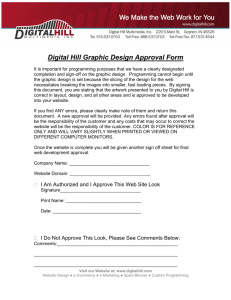

advertisement