4 Liberal Theories of International Law

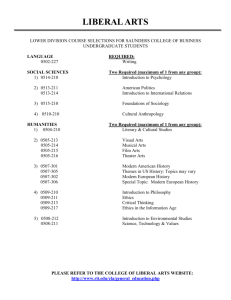

advertisement