URBAN AND TECHNIQUES RONALD LLOYD ESTER

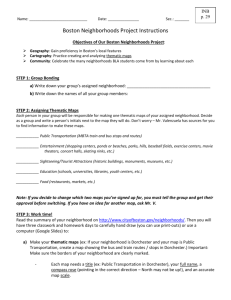

advertisement