(1969)

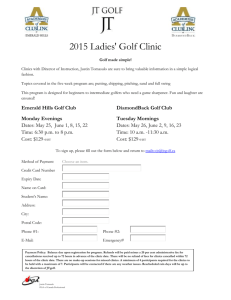

advertisement