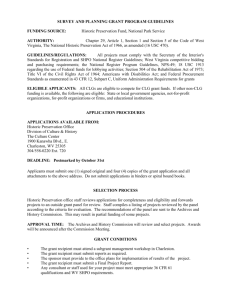

©

advertisement