HOUSING AND by (1969)

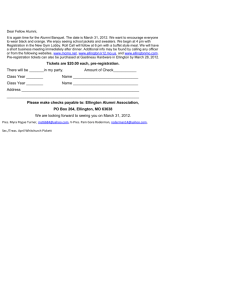

advertisement