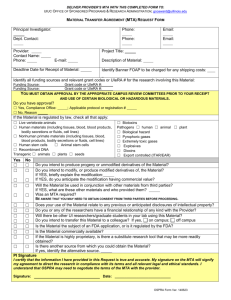

(1968)

advertisement