Document 10640789

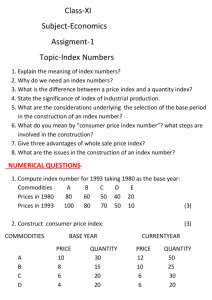

advertisement