Basil Joseph Tommy Submitted in Partial Fulfillment 1979

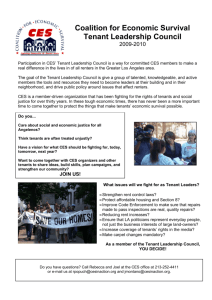

advertisement