by

advertisement

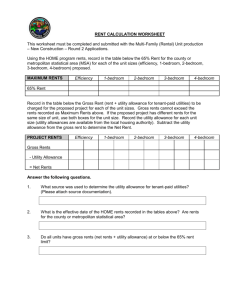

THE INCIDENCE OF REAL ESTATE TAXES ON OFFICE RENTS IN THE GREATER BOSTON AREA by THEODORE SYLVAN SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENTS OF ECONOMICS AND URBAN STUDIES AND PLANNING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREES OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ECONOMICS and MASTER IN CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTES INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1985 Massachusettes Institute of Technology 1985 Signature of Author...................................- Department of Urban Studi -...... and Planning May, 1985 .. .t Certified by................. Professor William Wheaton Thesis Supervisor Accepted by..... or Philip Clay Profe Chair an, MCP Program (/ MAS3SACHUSETT N OF TECHN0LOGY JUL 111985 .11 UE THE INCIDENCE OF REAL ESTATE TAXES ON OFFICE RENTS IN THE GREATER BOSTON AREA by THEODORE SYLVAN Submitted to the Departments of Economics, and Urban Studies and Planning on May 22, 1985 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degrees of Bachelor of Science in Economics and Master in City Planning ABSTRACT Area was Data on 160 office buildings in the Greater Boston collected as used in regressions in order to measure the tenants. Variables incidence of real estate taxes on office number of floors; number for were: building age; controlled in an office buildings of square feet per floor; number of number of highways number of nearby subway lines; park; through the town; and percentage of college educated people in no linear model showed the surrounding area. A simple taxes to tenants. A non-linear significant passing on of simultaneous equation which takes account of the dependence of unexpected results; taxes on gross rental rates demonstrated rents were found to fall with increased taxes. this study. The resultant of two forces is being observed in First is the passing on of increased taxes to tenants. Second, suburban towns tend to lower their tax rates as rents increase because their expenditures can be supported with a lower tax rate if property values are high. In the cities (i.e. Boston,) where budgets are strained, the second force should not operate. In the Boston suburbs, though, the second force apparently dominates the first. Thesis Supervisor: Title: Prof. William Wheaton Professor of Economics and Urban Studies Page 1 I. Introduction. Property and municipalities tax a rates body of literature exists substantial and postulating the incidence of these taxes on owners of between greatly vary users real estate. Data on 160 office buildings from 20 towns in the Greater Boston Area will be used to differential property test the impact of tax levels on office rents. A positive taxes impact implies that higher are passed on to office renters. The incidence property tax, has of been taxes on property in 1956 on the the the subject of numerous theoretical papers and empirical studies since Charles (1) values, locational Tiebout's article decision making process of individuals. Peter Mieszkowski(2,3) formalized the theoretical arguments regarding the incidence of the property tax late in the 1960's and early 1970's. From that time, two theoretical camps have evolved, the traditional or old view and the new view. Under the traditional theory, the essentially a profits tax and is born property by tax is the owners of Page 2 is capital. Capital is immobile and the amount of land in use the Because fixed. output remains factor constant. production is constant, in mix markets Assuming are in already an owner will not be able to raise the price for equilibrium, his output and will therefore bear the full cost of the tax. Holding capital and land in use constant assumption realistic to not a new view allows for the The make. is mobility of capital, but not land, so the tax on land falls on Most landowners. tax property papers which postulate fictitious national is borne by all owners of capital in the short run. Local differences from passed a this "national rate" are partially to consumers of products in the long run on since the capital-labor mix is modified over time so that less capital is used in high tax areas. The final theoretical model presented in this will assume paper complete mobility of capital and land use, and a general equilibrium framework for solving for incidence will be used. With land considered a variable factor, theoretically land taxes can be shifted to tenants to a degree dependent upon the relative price elasticities of supply and demand land, just like in the familiar for case of an excise tax on cigarettes. Measuring the degree to which commodity the substitution of capital prices and for labor reflect property tax Page 3 brokerage firms. in the Boston area through major tax rates controls for other variables The approach in taken have taxes effect while allowing for observation of the rents. office for index Creating a hedonic price includes which rents available readily is data rent However, office levels would be very difficult at best. on real estate tax estimating incidence will be to develop a simultaneous equation model and regress office rents on the control variables. space of foot will indicate demand elasticity the landlords and tenants, which approximates the burden between relative the square per taxes The resulting coefficient (c) on of If demand is perfectly elastic, then c is curve. zero and the landlord pays the full burden; a completely inelastic demand curve would imply that differential taxes can be completely passed on to tenants and c would be one. on current theory, c should empirical results be one. and zero between Based The will contradict the theory presented, lead to speculation on causality and suggest future paths of study. Knowing the elasticity of rent payment they can recover. information can sway the decision of whether to build in a town with low rents and low taxes or taxes, to is valuable to office developers in that it enables them to predict how much of their tax This respect with demand helping high rents and high suppliers to maximize and eventually equalize rates of return across all jurisdictions in a market. Town Page 4 officials tax can rates collections. on indirectly market calculate the /affect of changes in value, thereby estimating total Page 5 II. Capitalization Theory. Property taxes payments to a in municipal the United government States are of a percentage of the value of the land and improvements on private property. real estate is subject annual While to property taxes, other capital is generally not taxed in this country, although some states do have certain wealth taxes. The valuation which the tax bill is based on is made by a local town assessor using various (and sometimes mysterious) Massachusetts, methods Proposition for 2 arriving 1/2, a at values. In voter referendum, has required cities and towns to assess property at "full market value." Furthermore, the total take for a municipality may not amount to more than 2.5% of the town's total valuation, although different rates may be used for different classes of property. in The five official Massachusettes are: industrial personal. and classes residential, Office of property commercial, space is office, included in the commercial class. Property is generally valued in the market place its fair market net rental stream, assuming that the current use is the highest and best applied by a discount or use. To the capitalization income stream is rate, and the market Page 6 value is obtained. "Fair market" net income current than because is income rather used income is often below current market due to old leases made early in a bull Rarely market. in history have long term leases been at above market rentals, and for the past several years rents have been rising in most areas. from Net rental income is derived by deducting the gross rents all annual expenses related to running a building. This in applies theory to owner-occupied buildings as well, though the net rent is an imputed real are there If one. estate taxes to be paid on the property, then these reduce the net income figure. The capitalization rate is market driven, interest that is to say it is based upon current amount the capital being directed into real estate and future of expectations of supply and demand in The rates, market. particular the building is thus its net income divided by of value the the capitalization rate. As an illustration, assume foot office building is rented that at a 100,000 square $23.50 per square foot (psf.) so that gross rents are $2.35 million. If expenses are $3.50 psf. then the net rent is $20 psf. or $2 million. If the market expects a capitalization rate of 8% then the value of the building would be $250 psf. or $25 million ($20/.08 psf.) Now assume that a property tax is levied upon the Page 7 building in the amount of $2 psf. This would reduce net income to $18 psf. and value would fall to $225 psf. from $250. The imposition of a property tax value of the land has significantly reduced the and improvements, by ten percent in this example. The $25 psf. reduction in value is equal to the capitalization of $2 psf. at 8%. (Smith, p. 177) The example above illustrates how real estate are capitalized into the value of the property taxed. It should be remembered at this point that this means the whole story, but illustration of tax incidence. taxes is not by any rather a very short run static Later on we will see that theoretically some or all of the property tax may be passed on to renters in the form of higher rents, thereby mitigating its effect on the property owner. Furthermore, no distinction is made here between land owner and capital owner, though theory indicates that disparate incidences on these two parties occur or can be imputed. The U.S. system does not impose flat per square foot taxes on property; rather property is taxed as value. This simultaneity percent of makes the after tax calculation of value slightly more difficult and is shown formula: V = (N-tV)/c where: a (1) by the following Page 8 V = value N = net income after expenses only t = tax rate c = capitalization rate solving (1) for V yields: V = N/(c+t) (2) Equation (2) states that the value of a property its net stream income capitalized at is a rate equal to the taxes no market capitalization rate in the presence of plus the tax rate. Of course, only overall capitalization rates are observed in the market with the tax rate already added in. Equation (2) also says that no matter what the from the previous example and a 100% tax would have rate is, will always have some value. Taking the numbers property the tax a value equal rate, the building to $20/1.08, or $18.50 psf. This compares rather unfavorably to the $250 psf. value if no tax levied, however as t goes to infinity, V only approaches were zero. The past several paragraphs have explained and derived a formula for the capitalization of property taxes. It assumes without any thought that real estate tax incidence is entirely on the property-building owner. be to develop the step will theory of incidence more fully as it has evolved from a static view incidence model. The next into a general equilibrium tax Page 9 III. Property Tax Incidence. Property incidence tax at least since the 1890's, but not until Tiebout's economists article in 1956 did the theoretical work contribution main Tiebout's to large a variety of up. heat to begin the field was on the demand side, where he showed that consumer's of property amongst by discussed been has could shop and benefit packages from tax different municipalities. Each consumer was free to choose the tax/benefit package that gave him the confined most Tiebout utility. himself to residential consumers, but the concept is generalizable to any entity in engaged for searching a location. A firm would clearly prefer to locate in a town with lower taxes and wider, better paved roads leading to the office building it intends to occupy, cateris parabis. The Old View. On the actual incidence of property taxes, there evolved however, a traditional view that the portion of the tax attributable to land fell entirely on the land owner, while the tax on improvements could be shifted to consumers. Land in itself has value because it is scarce, highly unique Page 10 derived value Land non-reproducible. locationally and virtually is the difference between the cost of constructing from and site the highest and best use allowed or feasible on the the capitalized value of that use. Property taxes are supposed to on separately assessed be the itself and on the land improvements to the site. completely fixed property tax, nor can the the factor, a escape the cannot landowner is land view, traditional the Because, under prior it be passed on if the market to This point implementation of the tax was in equilibrium. is illustrated by the graph in figure 1. The supply of land is fixed and therefore vertical; for destroyed neither factors other they as optimal mix for their needs. view the then, imposition demand curve to D'. changed (the landowner demand must now equilibrium the nor created. Demand, D, to substitute flexible as users of land are free however, is it is land price, no matter what wish in order to obtain the From the land owner's of point of the tax lowers the effective While the actual equilibrium price has not curve pay has not shifted D), from the part of his rent in taxes. Thus the owner's perceived rental price is reduced by the full amount of the tax since his supply curve is completely inelastic. The story is different improvements. in the case of taxes on Here the traditional view holds that capital is mobile and that a local tax will drive capital away from the Figure 1 Landlord Rent After Tax Page 10A Supply .1 1 Demand R'=R-T Land in use Change in taxes per square foot is completely absorbed by Landlord. Figure 2 Lanlor' d Rent After T axes Supply R Demand R-T R'>R-T Space Change in taxes per square foot is partially passed on to Tenant. Page 11 amounts of capital will raise the market rents Reduced area. for buildings, passing on some of the tax burden The renters. to graph in figure 2 shows the supply, S, and demand, D, for owner. structures from the point of view of the building analysis elasticity of building the land market in that the of that from differs supply The is Therefore, positive. the extent to which the real estate tax is passed on is a function of relative elasticities of supply and demand just as in the the familiar case of a sales tax on cigarettes. The New View. In recent years a property taxes has new view of incidence the of emerged, pioneered by such economists as Mieskowski, Aaron, Musgrave and Netzer. The analysis begins by postulating the imposition of a uniform national forms of land and tax on all capital. Because both land and aggregate capital are assumed to be constant in the short run, owners of these factors will have to bear the entire burden of the The reasoning the case of tax. for this resultant incidence is the same as in land under the old view: commodities with perfectly inelastic supplies bear 100% of the taxes imposed on them. The new view analyzes the long run effect of Page 12 on taxes property aggregate substitution of capital for other factors of a of imposition greater the its than factors of production achieve the production. The national tax on capital will, in the short, optimal will price factor run bear on the capital owner. But with the capital and formation capital of marginal product, over time other substituted be production mix. for capital to In the long run then, increased taxes will reduce the aggregate amount of capital in existence. However, the factor price of capital will still be higher at the long run equilibrium point than initially. Since before any taxes are imposed, the world is assumed to be using an optimal mix of factors in production, the resultant change in this production mix must be suboptimal and the supply curve must shift such that higher prices are needed same level of output. to the induce Thus real estate taxes are partially shifted to consumers through increases in product prices. If city A imposes a national property tax the of top on some capital will leave city A and be added to tax, all other cities and towns. In equilibrium, the after tax rate of return to capital must be equal across all jurisdictions, so when city A imposes an excess tax, the return on capital is reduced and capital begins to flow to other areas where the after tax return is higher. As capital flows out its supply is being of city A, reduced, and since the demand curve is negatively price elastic with respect to quantity, the price of capital in city A rises until the return to capital reaches Page 13 the national level and the outflow ceases. In figure 3, effective supply shifts to either S' due to a change to suboptimal production methods or increased local taxes in one jurisdiction. The new equilibrium price is greater than the initial price, so that some of the tax burden has been shifted to consumers. The New View has come theory full circle to the excise of the old view for taxes on capital. Its contribution however is to remove the analysis away from the simple supply and demand graphs into a deeper micro-economic analysis of the problem. In order to fully analyze the incidence of a property needs not only a demand function, but also the now one tax, relevant production functions to curve. The New arrive at the new supply View allows for long run variable levels of capital, but not land. This subject will be broached next. Land as a Variable Factor. The idea that the total land in use may not be fixed has been developed by Aaron. While the total of physical supply land is fixed, except for certain natural phenomenon, land filling and regrading, the amount of given use may land dedicated to any be affected by the level of taxation for that Figure 3 Page 13A Tenant rent s' Supply R' RDemand Space Factor mix is changed, supply of space is reduced and rent increases to partially pass a tax increase on to consumers. Figure 4 Tenant Rent Supply s' RR'. Demand S S' Land in use Reduced taxes in the city lead to an increase in the supply of urban land, lowering rents. Page 14 surrounded use. In Aaron's example, a city that is completely by farm land is postulated. At the moment, all markets are in equilibrium so that the supply of land and capital in the city receives a market rate of return. If were return to capital and land would increase the lowered, rate tax property the and because tax payments would fall. As the amount of capital land in increases, use a declines until new the rate of return to these factors equilibrium is reached at a point somewhere above the initial market rate (see figure 4.) While the possibility of expanding the capital stock would be well accepted by most, expanding the stock of land is One not generally thought possible under conventional theory. must then realize that the farm land in this surrounding illustration represents an untapped supply of for available land addition to the city's stock. That total farm land in use declines is a consequence of the increased to relative urban cost use after the tax cut. of farmland The presumption is that after the tax cut some farm land becomes more valuable as urban land since the after tax rate of return has increased on urban land while that on farm land has remained the same. The amount of farmland incorporated into the city is tempered by the price elasticity of demand for capital and land. If the amount of land available in any given area for any given use can vary with the tax rate, then part of the burden of a property tax can be shifted to the users of land Page 15 and structures. Landowners should be no different from capital shift owners in their ability to customers. land However, the use regulations variations in the amount of land given to thereby forcing tax incidence upon Unfortunately, this study cannot show the of land taxes burden tax a can to restrict particular the relative their use, landowner. incidence on landowner and building owner, but only the final incidence of land and building taxes on office tenants. Page 16 IV. The Model. on gross rents should bear a direct relationship typical its are buildings to the tenants of the buildings then the on part in passed paid taxes If differentials in to The taxes. unit in an office building is the square foot, though definition exact not is as pure as it seem. may if we consider gross rents per square foot Regardless, real different across buildings that pay estate (psf.) taxes per square foot but have similar quality characteristics, then tax incidence can be estimated by regressing gross rent psf. on taxes psf. The resulting linear equation would be: R = a + b*X + c*T where R is the gross rent, X is a matrix of quality variables, T is the tax psf., and a,b and c are constants. The constant, c, represents the extent to which real estate taxes are reflected increase, a fraction, c, in gross would rents. fall If T were to on the tenant in the building. Thus if c is greater than zero, some portion of real estate taxes is passed on to the tenant. If c were zero less than then increased taxes would result in reduced gross rent, Page 17 meaning that an excess burden would be placed on the landlord, while if c were greater than one, the landlord would actually be predicted to realize increased profits as taxes rise. Since both of these seem possibilities far one would fetched, strongly expect to find c to be between zero and one. appropriate This linear specification would be taxes if estimation bore no relationship to property value. system However, the very nature of the property tax that taxes be for to value. related dictates Furthermore, as mentioned above, Proposition 2 1/2 in Massachusetts requires 100% market valuation for tax purposes. Since value is a function of gross rent, simply using taxes per square to equivalent variable is equation since specification model for rent, taxes problem are foot as an independent having rent on both sides of the function a of value. This can be fixed by solving the structural resulting in a non-linear equation. resulting model to be estimated appears on the next page. The Page 18 Structural taxation model: R = a+bX+cT (1) T = Vt V -> = (R-E-T)/d T = ((R-E)t/d)/(1+t/d) Substitute T into (1): R = a+bX+c[(R-E)t/d] (1+t/d) -> R = a+bX-[cEt/(d+t)] ---------------- (2) [1-(ct/(d+t))] where: = = = = = = = Gross rent psf. Taxes psf. Tax rate. Value. Expenses psf. Matrix of building qualities. discount rate. a, b, c = constants. R T t V E X d Page 19 In the preceding equation, the incidence of the is still explained by property the coefficient, c, of the taxes per square foot. The expected value of c would be the same the linear case. tax as in Page 20 V. Analyzing Real Estate Tax Incidence for the Greater Boston Office Market. The insurance, total real number estate of and workers in 1984. predominantly increasing in These office demand the finance, other service industries in the United States has increased from million in 3 in million industries buildings. employ 1955 their Coincident 11 to workers with this for additional office space, the supply of space has expanded to 3.5 billion square feet from 1 billion. New construction has been at record volumes for several years. (Wheaton.) The office market in Greater Boston has been one the of hottest in the country over the past decade. A tremendous rejuvenation has occurred in Boston through the young professionals into the city. migration Office employment has expanded, with several new buildings having been 1975. Growth of built since in the suburban office market has ridden on the catalyst of the high-tech industry which has concentrated around the inner-belt highway 128. If demand is stable in a market, office supply decline for there to be a passing on of a tax increase in the form of higher rents. slow, must so a change Depreciation of real estate in the is fairly tax rate will put the market in Page 21 disequilibrium for expanding years. several of presence taxes on office buildings becomes much more accelerated. capital and are supply land an the long run incidence of property market, office the In fluid Both with respect to taxing jurisdictions. If demand is increasing on the order of 3 to 4% per year, changes in tax rates supply need only remain are stable quickly passed The on. for rents to begin rising, passing tax costs on to tenants in a fairly short time. If different jurisdictions have different tax rates, then developers of office space will adjust the volume of so construction that the rate of return on buildings will be equalized over all municipalities. The amount of land for new in use office space will be varied in the same way, meaning that taxes on land increased will land be taxes partially will lead passed on. developers Furthermore, to attempt to increase the density of floor space per unit of land as taxes increase the factor price of land. The rapid growth in of office market therefore the dictates Greater that equilibrium. Thus when estimating the taxes, the results or other incidence of property should yield the full extent of the long areas of imputed extent prices tax incidence in where real estate is substantially owner-occupied is difficult because factor Area's it be near long run run shift of burden. Analyzing real estate industry Boston and the a lack of of data on capital-labor Page 22 substitution in the production mix. However, studying a rental market can provide the necessary data for assessing incidence on tenants. The rental office market in Greater Boston this opportunity accessibility brokerage of firms to determine good market provides tax incidence because of the data. At least two major provide a very complete survey of the office market, including asking rents, vacancy rates, size, number of floors, location and age. Furthermore, the fact that this data is available to both renters and owners should make the market very efficient. Data on land and building tax assessments and the town tax rates are available from local town these can be derived a building's tax halls. payments From and its effective tax rate (taxes divided by capitalized value.) The question we seek incidence of property taxes to answer is, on these office buildings? If what is the property taxes are thought of as part of annual expenses, then an increase in taxes, say per square foot, is paid in cash the by landlord. The only way to shift this burden to the tenant is for the landlord to raise the gross rent. Thus the relevant question to be answered becomes, to what extent does an increase in taxes per square foot get passed on as an increase in gross rents? An econometric model of tax incidence will be developed and estimated with data on 160 office buildings from the Boston Area in section VI. Page 23 The Sample. Greater Boston Area the distribution the in The sample consists of 160 office buildings of which follows the A.) distribution of office buildings in the region (see Table Approximately 25% of the buildings are located in Boston, some of are which outside the Central Business District. Several other buildings are located in two adjacent cities, and Brookline. The rest Cambridge the sample is from the suburbs of located around a circumferential highway known as The 128. office market around the 128 belt, which has grown up over the past two decades, can be considered rather uniform in terms of its access to central Boston. Thus, comparing tax incidence across these towns should yield good results. All of the buildings in the sample were built to 1980, and since the data is from early 1985, all of these buildings are older than 5 years. New buildings additional prior attraction high rents, unexplained which by could the may have an translate into unusually sample data. These mature buildings should now have gone through releasing at least once and lost any original luster. Page 24 Table A: Town Statistics. Town No. Bldgs. RATE1 RATE2 Boston Cambridge Brookline Bedford Braintree Burlington Canton Dedham Framingham Lexington Needham Newton Peabody Quincy Stoneham Wakefield Waltham Wellesley Weston Woburn 40 11 5 2 7 20 1 3 3 12 1 11 2 2 1 3 11 21 1 2 3.1% 3.5% 3.2% 2.2% 3.7% 2.2% 2.0% 3.0% 2.5% 3.0% 1.6% 3.4% 2.4% 3.1% 2.1% 3.0% 3.1% 1.6% 1.6% 2.6% 2.1% 2.6% 1.8% 1.3% 1.3% 1.1% 1.0% 1.3% 1.7% 1.6% 0.8% 2.3% 5.2% 1.5% 1.1% 2.2% 1.5% 0.8% 2.3% 1.0% Page 25 allow The control variables in the data base should the effect differential taxes have on rents to come through in the These regressions. variables quality and location. It is vital fall into two categories: that the sample contain information which differentiates both between buildings in the same and town similar buildings in different towns. Two buildings in one town will have different rents based on their attributes of quality and functionality. A building in one town would have a different rent if placed in another location with a transportation, different worker access and public benefit package. The variables used in the sample capture of much this attempt to variation, and do, but others, though less attainable and definable, would greatly add to the power of this study. Important location variables ease should represent the of access a building has to its customers and workforce. Access to major ability of highways and transit lines represent workers and clients to reach the office building. Access to the white collar work force is demonstrated percentage the of by the college educated people in the immediate area. Controlling for these quality variables allows for rents to be compared across jurisdictions with differing tax levels. Using asking rent may be a problem in a soft if concessions are being market made in leases. These concessions Page 26 for paid improvements include free rent and tenant by the landlord which reduce the effective gross rent received by the free on Data landlord. rent periods and tenant work should ideally be converted into an income stream over the lease term difficult and subtracted from asking rent. It is far more collect this information on each to building since it is not published by brokers and is not readily disclosed by landlords or tenants. Other variables which would more completely describe building quality and location would from attainable sample. the The improve information the presence of a cafeteria, degree of landscaping, expenditures on maintenance per square foot, views, architectural significance, and amount of parking per square foot (relative to neighboring buildings) should be included as additional quality variables. Travel time airport as well to the a more detailed measure of the level of as road service (i.e. number of lanes) could significant be as far as transportation access is concerned. Labor supply is not well measured by the percentage of college educated people in the area. Some measure workers, of actual numbers of white collar and top executives, residing around the town, scaled by surrounding office space, would be desirable. Fiscal variables should be well since public taken into account as spending which benefits office users will offset tax costs and tend to raise rents. Office tenants do Page 27 not directly in much use services, although of way the and spending on roads, utility provisions, police, sanitation fire could benefit firms. Office workers can derive fighting parks and traffic control systems. Furthermore, moderate tax induce rates combined with excellent schools can live a in particular area, affect to workers jobs office nearby making appealing. All of these factors can as items such on substantial benefits from public spending and rents gross attempts to consider them are important. Hedonic rent indexes are estimated for the sample in order to separate the effect of taxes out from affecting on several variables was collected for Data rent. building number (FLOOR), of square constructed rehabed or (AGE) bills were looked up at and age came from market study reports from two major brokerage firms in the tax floor per feet (SQFTFLR), number of buildings in the project (BLDG) since in floors each building. Gross asking rent (RENT), number of the factors other town area. Property The number of halls. mass-transit lines (TRAN) and highways (HY) which the building has convenient access to was included in the data base. Finally, the percentage of population in the surrounding towns with college education (COLLED) was measured (see Table B.) FLOOR, SQFTFLR, BLDG and AGE fall into category. Rent the quality should be related positively to the number of floors, since upper floors generally demand a rental premium. Page 28 Number of square feet per floor should have a positive impact on rent since tenants with larger needs more easily. Agglomeration affects can be accommodated in the form of multiple buildings in a single project should also yield greater rents. The age of the building is a good proxy for its level of service and condition, and should have a negative influence on rent levels. However, the upwards in magnitude because time restrict supply, age rising leading rents for newer buildings. coefficient to may development be biased costs over accelerated increases in Page 29 Table B: Variable Definitions. Name Definition RENT Gross asking rent for the building. FLOOR Number of floors in the building. SQFTFLR Total square feet in building divided by FLOOR. BLDG Number of buildings in the surrounding office park. AGE Age of the building HY Number of major highways through the town building is located in. TRAN Number of mass transit (subway) lines with stops within one mile of building. COLLED Percentage of the population in the surrounding area with college degrees. RATE1 Town's legal commercial tax rate. RATE2 Calculated average effective town tax rate. (1985-year built.) Page 30 VI. The Regressions. As a base case, ordinary linear regressions were run with rent as the dependant variable for the entire sample; the suburban towns; and the three inner cities, Boston, and Cambridge Brookline together. The reason for breaking the data this 'Suburban' way is that the office suburban towns Thus, market. are there sub-sample and each town is in the same three cities have access to therefore more closely linked. located in the is uniformity in this general mass-transit market. The and are lines Though Boston is probably in a class by itself, the variables HY and TRAN should account its especially high appear in Table 1. Most 128 for rents. The results of these regressions of the variables are significant, although several are insignificant in the city regression. The R-squareds data. for each regression are high for cross-sectional Page 31 Table 1: Ordinary least squares regressions. Regression Variable All Bldgs. Suburbs City constant 11.70 (11.03) 10.19 (8.21) 19.29 (3.26) -. 0812 -. 138 (2.77) -. 109 (3.60) Age (3.30) Floor .212 (6.43) Sqftflr .0000146* .217 (4.93) .0000259 (2.08) -. 0000495* (.793) .455 (5.63) .514 1.46 (7.03) (2.59) Colled 22.92 (6.78) 19.07 (5.39) 2 .65* (.102) Tran 1.52 (6.26) Hy .0724 (.282) 1.22 (2.93) .312* (.838) T (c) .131* (.716) .204* (.705) - 64.1% 54.3% 58.8% (1.05) Bldg R-squared * Coefficient not significant. t statistics are in parenthesis .746* (1.85) .333* (1.32) Page 32 There is a significant constant in each a higher constant than the the city has suburbs. Therefore, the same building and expected, as generate gross higher rents. regression, Age the in strong a has should city negative influence on rents, though slightly higher in the suburbs than the city. Each year a suburban building ages, expected rent is reduced $.14 psf. psf. while city buildings' rents fall $.11 each year, on average. Size of a building should influence rent positively. terms Being on a higher floor is worth a premium in floor, enables large firms to fit more space efficiently. is floors fewer on stories, firms may available. Typical and space Vertical detrimental in the city for cultural reasons and be because most buildings have small 10,000 however The number of square feet per floor is only significant in the suburbs. suburbs use from the city regression that additional floors clear bring additional rents of $.22 psf. not and FLOOR could not be estimated in the suburbs because the buildings were all four may view prestige. Having a larger footprint, more square feet per and it of demand buildings while in space which is more have between horizontal in the footprints, the suburbs 50,000 square feet per floor, implying a possible rent premium of up to $1.00 psf. for larger footprints. The location variables function well in this market. Page 33 Agglomeration affects are the by evidenced as positive significant positive coefficients on BLDG for each regression. parks Office bring building, while in the Overall, the expected $.51 psf. the city higher, is effect each for rent additional $1.46. rent per building is over additional $.45 psf. COLLED, a measure of access to the white collar work force, is very significant to and sample overall the the suburbs. Firms pay more rent for locations convenient to their workers. access TRAN, insignificant to is just barely in the city, but it has a positive coefficient, as expected. In the overall increases lines lines, subway gross rent access sample, by psf. estimated for the suburbs because the $1.52. transit mass-transit to TRAN is not lines do not operate there. The number of highways running through suburban towns has a large positive affect on rents. Thus, the greater the transportation access to a building, the greater the rent. The variables TRAN, HY and COLLED did not work in the together city regression because of the limits of this sample. The results from the total sample COLLED. well are better for TRAN and Boston creates problems for the highway variable, so it is only significant in the suburban regression. Finally, the variable which we are most interested in, taxes per square foot (T) has an insignificant coefficient in all regressions. It could be stated naively at this point Page 34 that property owners bear the full burden of the property tax. This is not necessarily true since the correct specification of the model involves a non-linear estimation. A major issue in specifying the non-linear model is what to use for the tax rate. Towns have established legal tax 2 1/2, property tax rates do rates, but even with Proposition not follow really the Capitalizing net income legal rate. after tax, and using this value and the tax bill to the determine on a particular building yields tax rates that vary rate would with a town often by 4 to 1 or more. An alternative be to take an average of the calculated rate for each building in the town and use that as the effective tax rate on the building. The two possible tax rates; the legal rate, and effective estimations. average legal used in six non-linear For each rate, the whole sample was estimated as well as a city and suburb with were rate; the rate estimation. The city regressions and effective rate did not come out because the sample is so limited, and thus these results are reportable. The regression results appear in Tables 2&3. not Page 35 Table 2: Non-linear regressions using 'RATE1'. Regression Variable All Bldgs. Suburbs Constant 15.29 (7.51) 14.98 (7.43) Age -. 0981 -.165 (3.08) (2.62) Floor .282 (5.28) Sqftflr . 0000179* (1.03) .0000362 (2.16) Bldg. .514 (5.04) .624 (6.33) Tran 2.20 (5.01) Hy -. 137* Colled Ratel (c) R-squared (.407) 1.17 (2.25) 26.12 (5.92) 22.95 (4.92) -1.20 (2.01) -1.75 (2.87) 65.4% 60.3% * Coefficient not s ignificant. t statistics are in parenthesis. Page 36 Table 3: Non-linear regressions using 'RATE2'. Regression Variable All Bldgs. Suburbs Constant 12.52 (9.77) 12.51 (8.81) Age -. 0850 (3.28) -. 161 (2.94) Floor .226 (5.78) Sqftflr .0000141* (.991) .0000298 Bldg .450 (5.44) .529 (6.66) Tran 1.69 (5.28) Hy .00178* (.00641) 1.09 23.54 (6.56) 21.62 (5.41) -. 260* (.629) -1.09* (2.24) 64.1% 57.0% Colled Rate2 (c) R-squared * Coefficient not significant. t statistics are in parenthesis. (2.14) (2.40) Page 37 Most of the coefficients were qualitatively no matter similar what tax rate was used. Therefore, running through these numbers in detail would not be interesting at all. As in the linear case, colinearity problems again affected the city regression. All regressions only were good cross-sectional fits with corrected R-squared's ranging from 55% to 65%. coefficient The tax psf. (T) each regression, it although the significant, except for was consistently negative and entire using sample effective rates. Effective rate is probably the best version of average the tax rate to use. It is because over greatly varied over improvement an rate legal properties just are not taxed at this rate. Using the calculated building rate presents problems because given the data available, the only way to do this calculation is to have the rate dependent on gross rent, thus introducing an additional simultaneity problem in the model. Taxes square that property owners bear taxes. The foot are not suburban the market, full burden however, has negative relationship between rents and taxes. unexpected and very surprising. this result is that tax rates in the rents. If a a significant gross rents over the whole sample. This implies on influence per of estate real a significant This is very A possible explanation for suburbs are driven by town has relatively valuable office space (high Page 38 is rate rents) then a lower tax needed to public finance expenditures. This influence would not be predicted for a city like Boston where fiscal difficulties necessitate that as much revenue as possible be soaked from all sources. One other econometric method for estimating property study. tax incidence should be pursued before concluding this Each because town, as desirable relative office an desirability attributes, its of location towns across than the various towns. These This others. the can be described as the same building rents are then difference in rent which would be paid for the in less or more is differential regressed against the townwide variables. This estimation is done in two stages. R = a+bX+cD (1) where: R = differential rent; a, b and c are constant; X is a matrix of building characteristics; and D is the matrix of dummy variables. D = e+fY (2) where: D is the vector of differential rents; Y is the matrix of town variables; e and f are constants. First, one dummy variable is created for except one, in this case Boston. (1) includes all town Boston is the base town against which all differential rents are measured. regression each building The variables: first FLOOR, Page 39 SQFTFLR, BLDG and AGE (Table 4A.) held constant so that the Thus the dummy building coefficients type is become the differential rents for each town. The second rents derived from regression (2) the regression first uses the differential as the dependant variable and the town variables; HY, TRAN, COLLED and RATE1 or RATE2; as independent variables. The coefficients of RATE1 and RATE2 indicate the incidence of the tax. The results of regressions are given in table 4B. these Page 40 Table 4A: Two stage estimation of tax rate effect; stage 1 results (Rents relative to Boston.) Variable Coefficient T statistic Constant FLOOR SQFTFLR BLDG 23.04 .178 .0000308 .444 27.74 5.72 1.93 AGE - Cambridge Newton -2.58 -4.21 -7.64 -9.56 -6.58 -6.29 -8.09 -5.42 -6.31 -4.49 * -4.02 Peabody -8.86 Quincy -10.17 -6.15 -12.11 -5.32 -1.20 * - .45 * -4.27 Brookline Bedford Braintree Burlington Canton Dedham Framingham Lexington Needham Stoneham Wakefield Waltham Wellesley Weston Woburn .0829 * Coefficient not significant. 5.09 3.60 2.91 3.37 4.12 8.70 7.01 2.45 5.24 3.49 6.65 1.76 4.28 4.78 4.37 2.41 7.85 5.52 1.51 .17 2.28 Page 41 Table 4B: Two stage estimation of tax rate effect; stage 2 results. Variable Ratel Rate2 Constant -10.16 (3.07) -12.18 (6.31) Hy .454* (.880) .561* (1.10) Tran 1.51 (2.42) 1.36 (2.26) Colled 21.59 (3.59) 22.76 (3.85) Ratel -72. 51* (.853) -22.88* (.440) Rate2 R-squared 55.6% * Coefficient not significant. t statistics are in parenthesis. 54.0% Page 42 Two regressions were run, one using using other (Table 4B.) All variables were entered in RATE2 linear form only since there is no structural model this for the and RATEl developed section. Both regressions have R-squared's of about 55%. Transportation lines have a positive influence on rent of to $1.45 psf. on average. The highway variable turned out insignificant, though this result would probably be different if only the suburbs were looked at. As anticipated, of white be collar workers to the location, proximity as measured by COLLED, brings a premium in gross rents. The results for taxes turn out to be which negative. Both coefficients were negative, could be explained if rental rates drive tax rates, and towns are not budget strained. However, these coefficients are not significant, thus it must be assumed that taxes are not being passed on to renters, based on these results. tax Although the two stage estimation of reveals incidence that landlords pay the entire amount of the tax, this result should not be looked at with too much confidence it was attained with regressions completely devoid since of a structural model much like with the original linear regression presented earlier. Some economic theory with a results applied here, along break up of the sample might lead to more interesting which would simultaneous model. coincide better with the non-linear Page 43 VII. Conclusion. The results of on presented property estimations show that on passed office to while that model show significant tax contradict study this occurs not are taxes property tenants. The results of the non-linear in the there sample total is no shifting of the burden to tenants, in the suburbs gross higher taxes are actually correlated with lower This theory Linear and two-stage incidence. differential the rents. despite the rapid growth occurring in the market which should allow developers to equalize their rate of return over the entire area. observation One explanation for this surprising that towns with more valuable office is space (higher gross rents) than others can support their expenditures with a lower tax rate, cateris parabis. If a town's budget is not strained, property values it can afford to lower its tax rates when suburban tax rates may be driven by rents increase. Thus rather than the other way around. We observe this in study only the resultant of two forces: landlords passing high taxes on to tenants, and towns lowering rates as values outpace spending. A problem with this study is its lack which measure of variables the package of public benefits provided by the Page 44 Town lines. subway town, other than simply the number of roads or on items benefiting office users and landlords spending would mitigate the net effect of the tax property these on Furthermore, spending patterns which benefit office parties. to workers living near the site may provide indirect benefits the in tenants form of an incentive for employees to live nearby, thereby lowering wage demands at the site. (Carlton) indicating Using a variable like COLLED, while white collar mix of the surrounding area, says nothing about wage the magnitude of the office labor force nor its other to relative of taxes, demands areas. A location may be ideal for office firms in terms of client access, but terms may unbearable, be in pollution, crime, etc., for workers to live near. On the other hand, if high tax collections are spent items the on substantially beneficial to firms or workers, these are likely to be passed on into greater willingness pay for measure the to office space. Nothing in this extent to which paper allows to us landowners and building owners divide their share of the tax burden. Most building owners are also fee owners so relative incidence would have to be imputed. Data on land sales might however the number reveal of real estate tax incidence on land, these cross-sectional analysis. sales would be too few for Page 45 In determinants conclusion, of town study more tax rates is needed should be included information, the passing on of observed in in the (and the appropriate rate to use in research.) Variables which measure the towns' pattern on the taxes sample. to Without tenants isolation from other fiscal factors. spending cannot this be Page 46 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. Henry J. Aaron, Who Pays the Property Tax? A New View, The Brookings Institute, 1975. 2. David E. Black, "Property Tax Incidence: The Excise Tax Journal, Effect and Assessment Practices" National Tax December 1977. 3. T. Brennan, R. Cannady and P. Colwell, "Office Rent in the Chicago CBD" ARUEA Journal, Fall 1984. Business Location" in 4. Dennis W. Carlton, "Models of New Movements and Regional Growth, Wheaton (ed) Interregional State-Local "Studies of Urban Institute 1976. John F. Due, Influences on Location of Industry" National Tax Journal, Tax June 1961. 5. William Fischel, "Fiscal and Environmental Considerations in the Location of Firms in Suburban Communities" in E. Mills and W. Oates ed. Fiscal Zoning and Land Use Control" Lexington Books, 1975. Interjurisdictional 6. Bruce W. Hamilton, "Capitalization of in Local Tax Prices" American Economic Review 66, Differences 1976. 7. Keith Ihlanfeldt, "Property Tax Incidence on Owner from the Annual Housing Survey" Evidence Occupied6 Housing: National Tax Journal, March 1982. 8. Charles McClure Jr., "The New View of the Property Tax: Caveat" National Tax Journal, March 1977. A 9. Peter Mieszkowski, "Tax Incidence Theory: The Effects of Taxes on the Distribution of Income" Journal of Economic Literature, December 1969. 10. Peter Mieszkowski, "The Property Tax: An Excise or a Profits Tax?" Journal of Public Economics 1, 1972, p. 73-96. 11. William E. Morgan, Taxes and the University of Colorado Press, 1967. Location of Industry, 12. Dick Netzer, "Economics of the Property Tax" The Brookings Institute, 1967. 13. Dick Netzer, "The Incidence of the Property Tax Revisited" National Tax Journal, December 1973. 14. Wallace E. Oates, "The Effects of Property Taxes and Local Tax Public Spending on Property Values: An Empirical Study of Page 47 Tiebout the and Capitalization Political Economy, Nov/Dec 1969. Hypothesis" Journal 15. Larry Orr, "The Incidence of Differential Property on Urban Housing" National Tax Journal, September 1968. 16. R. Stafford Smith, "Property Tax Capitalization Francisco" National Tax Journal, June 1970. of Taxes in San 17. Charles M. Tiebout, "A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures" Journal of Political Economy, October 1956, p. 416-424. 18. T.J. Wales and E.G. Wiens, "Capitalization of Residential Property Taxes: An Empirical Study" Review of Economics and Statistics, August 1974. 19. William C. Wheaton and Raymond G. Torto, "The National Office Market: History and Future Prospects" 8/8/84. 20. William C. Wheaton, "The Incidence of Inter-Jurisdictional National Tax Differences in Commercial Property Taxes" Journal, December 1984.