Document 10640715

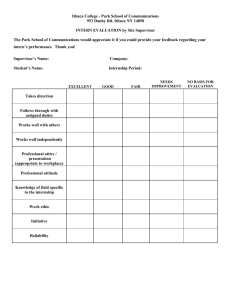

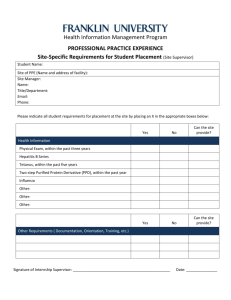

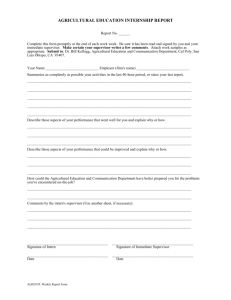

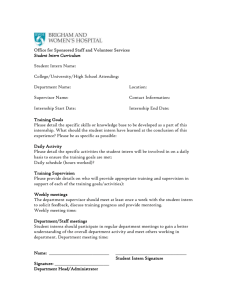

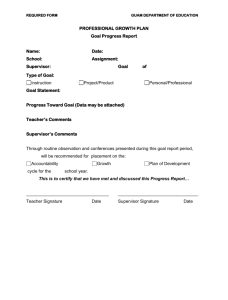

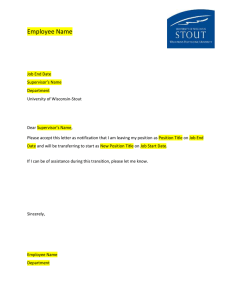

advertisement