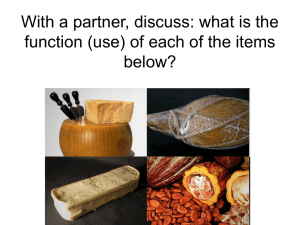

Design of Currency, Markets, and Economy ... Dawei Shen

advertisement