E Z G

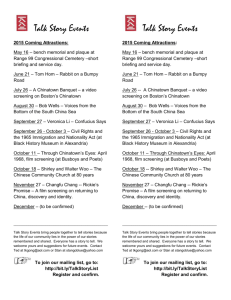

advertisement