Document 10629944

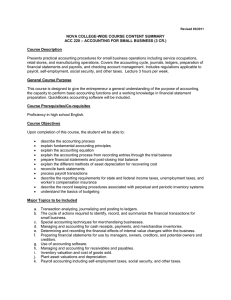

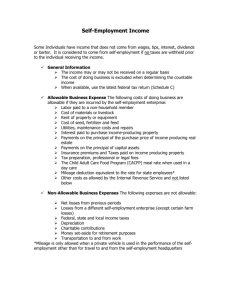

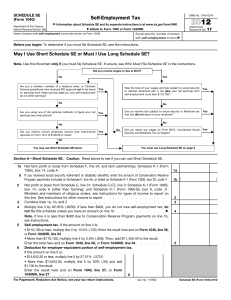

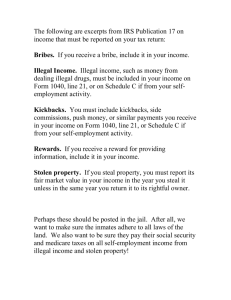

advertisement