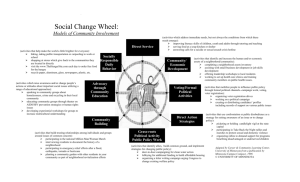

4 MODEL 1WHY

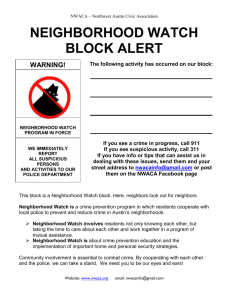

advertisement