UNEVEN ECONOMY PAUL

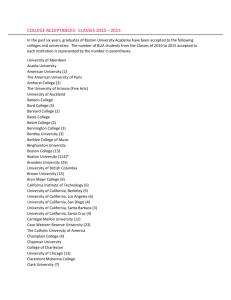

advertisement