Long Term Degradation of Resin

advertisement

Long Term Degradation of Resin

for High Temperature Composites

by

Kaustubh A. Patekar

B.Tech., Aerospace Engineering (1995)

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, India

Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

in partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the degree of

Master of Science

in Aeronautics and Astronautics

at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

September 1998

© Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1998

All rights reserved

Signature of Author

Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

June 19, 1998

Certified by

Hugh L. McManus

Associate Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by

S ~47ii Professor

Peraire

Associate

Chairman, Department Graduate Committee

INSTIThTE

MASSACHUSETrS

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

I

OF TECHNOLOGY

SEP 2 2 1998

LIBRARIES

1

LONG TERM DEGRADATION OF RESIN FOR HIGH

TEMPERATURE COMPOSITES

by

Kaustubh A. Patekar

Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on June 19, 1998 in partial

fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Aeronautics and

Astronautics

ABSTRACT

The durability of polymer matrix composites exposed to harsh

environments is a major concern. Surface degradation and damage are

observed in polyimide composites used in air at 125-300'C. It is believed that

diffusion of oxygen into the material and oxidative chemical reactions in the

matrix are responsible. Previous work has characterized and modeled

diffusion behavior, and thermogravimetric analyses (TGAs) have been carried

out in nitrogen, air, and oxygen to provide quantitative information on

thermal and oxidative reactions. However, the model developed using these

data was not able to capture behavior seen in isothermal tests, especially

those of long duration. A test program that focuses on lower temperatures

and makes use of isothermal tests was undertaken to achieve a better

understanding of the degradation reactions under use conditions. A new,

low-cost technique was developed to collect chemical degradation data for

isothermal tests lasting over 200 hours in the temperature range 125-300'C.

Results indicate complex behavior not captured by the previous TGA tests,

including the presence of weight-adding reactions. Weight gain reactions

dominated in the 125-225oC temperature range, while weight loss reactions

dominated beyond 225 0 C. The data obtained from isothermal tests was used

to develop a new model of the material behavior. This model was able to fully

capture the behavior seen in the tests up to 275°C. Correlation of the current

model with both isothermal data at 300 0 C and high rate TGA test data is

mediocre. At 300'C and above, the reaction mechanisms appear to change.

Attempts (which failed) to measure non-oxidative degradation indicate that

oxidative reactions dominate the degradation at low temperatures. Based on

this work, long term isothermal testing in an oxidative atmosphere is

recommended for studying the degradation behavior of this class of materials.

Thesis Supervisor:

Title:

Hugh L. McManus

Associate Professor

Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A number of people contributed in various ways towards this endeavor.

First of all, I would like to thank Hugh, my advisor, for his guidance and

encouragement. I have enjoyed working for him. The discussions I had with

him helped form the basis of this work and his suggestions were

instrumental in making my life a lot easier.

I would also like to thank Paul, Mark, Carlos and Prof. Dugundji for

their comments and questions during TELAC presentations. The discussion

on issues raised during these talks helped to improve the quality of this work.

John Kane's help in getting my long-lasting tests done is greatly appreciated.

Deb, thank you for keeping me company while waiting for Hugh and

enduring my " Where is Hugh ?" questions, especially during the last two

months. Thanks Ping for decoding all those requisition forms. Thanks are

due to my UROPers Jeff Reichbach and Ryan Peoples, for going through

numerous catalogs and building the experimental set-up.

I owe a lot to other grad students in the lab, who have made this time

fly by. Chris, for keeping me company while working at ungodly hours in the

office (I have never seen him leave for the day). Tom, for being nice and

letting me use the thermal chamber for a really long time. Lauren, Brian

and Dennis for all those chats, which were good, relaxing breaks. All those

who have offices in 41-219, for sharing the joy of working in a place that

continues to oscillate between the equator and Antarctica.

Last, but not the least, I would like to thank my parents and brother,

Shailesh, for their continued support and encouragement.

FOREWORD

This work was conducted in the Technology Laboratory for

Advanced Composites (TELAC) in the Department of Aeronautics and

Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

This work was supervised by Dr. K. J. Bowles of the NASA

Lewis Research Center and was carried out under Grant NAG3-2054,

"Improved Mechanism-Based Life Prediction Models."

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

7

LIST OF TABLES

8

NOMENCLATURE

9

1. INTRODUCTION

10

2. BACKGROUND

15

2.1

PREVIOUS EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES

16

2.2

POLYIMIDE CHEMISTRY

19

2.3

PREVIOUS ANALYTICAL WORK

22

2.4

RECENT WORK

24

3. PROBLEM STATEMENT AND APPROACH

28

3.1

PROBLEM STATEMENT

28

3.2

APPROACH

28

3.3

ANALYTICAL TASKS

29

3.4

EXPERIMENTAL TASKS

29

4. ANALYTICAL METHODS

31

4.1

DEGRADATION MODEL

31

4.2

DETERMINATION OF KINETIC CONSTANTS

35

4.3

MODEL IMPLEMENTATION

36

4.4

DATA REDUCTION IMPLEMENTATION

36

5. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

39

5.1

MATERIAL MANUFACTURE AND PREPARATION

40

5.2

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE FOR ISOTHERMAL

42

TESTS

5.2.1

Experimental Set-up

42

5.2.2

Tests in Air

43

5.2.3

Tests in Nitrogen

46

6. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

48

6.1

6.2

LONG TERM ISOTHERMAL AGING TESTS IN AIR

48

6.1.1

Experimental Data

48

6.1.2

Data Reduction and Correlation

58

LONG TERM ISOTHERMAL AGING TESTS IN

68

NITROGEN

6.3

7.

COMBINED MODEL

72

77

CONCLUSIONS

79

REFERENCES

APPENDIX A

MATLAB CODES

85

APPENDIX B

ISOTHERMAL AGING IN AIR TEST DATA

96

LIST OF FIGURES

1.1

Complete analysis for composite degradation

12

5.1

Schematic of specimen and thermocouple location in thermal

environment chamber (not to scale)

44

5.2

Schematic of atmosphere control system for aging tests in inert

atmosphere

47

6.1

Isothermal aging test in air at 125°C

50

6.2

Isothermal aging test in air at 150'C

51

6.3

Isothermal aging test in air at 175°C

52

6.4

Isothermal aging test in air at 200°C

53

6.5

Isothermal aging test in air at 225°C

54

6.6

Isothermal aging test in air at 250°C

55

6.7

Isothermal aging test in air at 275°C

56

6.8

Isothermal aging test in air at 300'C

57

6.9

Model comparison with isothermal aging test data in air at 150'C

61

6.10

Model comparison with isothermal aging test data in air at 175°C

62

6.11

Model comparison with isothermal aging test data in air at 200°C

63

6.12

Model comparison with isothermal aging test data in air at 225°C

64

6.13

Model comparison with isothermal aging test data in air at 250'C

65

6.14

Model comparison with isothermal aging test data in air at 275C

66

6.15

Model comparison with isothermal aging test data in air at 300°C

67

6.16

Isothermal aging test in nitrogen at 125°C

69

6.17

Isothermal aging test in nitrogen at 200°C

70

6.18

Isothermal aging test in nitrogen at 300°C

6.19

Comparison of combined model prediction with 5C/min.

heating rate TGA data in air

Comparison of combined model prediction with 20C/min.

heating rate TGA data in air

71

74

6.20

75

LIST OF TABLES

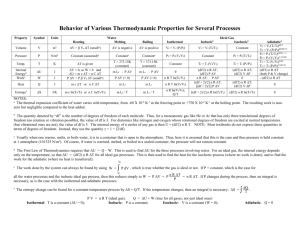

5.1

Neat resin isothermal exposure test matrix

41

6.1

Coefficients for the new three reaction model

60

6.2

Coefficients for the combined five reaction model

73

B.1

Data for test at 125 0 C

96

B.2

Data for test at 150 0 C

97

B.3

Data for test at 175 0 C

98

B.4

Data for test at 200 0 C

99

B.5

Data for test at 225 0 C

101

B.6

Data for test at 250 0 C

102

B.7

Data for test at 275 0 C

104

B.8

Data for test at 300 0 C

105

NOMENCLATURE

cox

cs

Ci

E,

Eij

F'(T)

F(ai)

k;

kj

mf

mi

mij

mo

msi

mfi

moi

ni

nij

Mo

M(t)

R

t

T

V

Yi

ai

ai,

Am

Am

Am'

Ami

AM

relative concentration of oxygen

relative concentration of species s

constant used for modeling reaction during data reduction

activation energy of reaction acting on component i

activation energy of reactionj acting on component i

temperature-dependence function

conversion-dependence function for component i

rate constant for reaction acting on component i

rate constant for reactionj acting on component i

final mass of unreacting mass fractions

mass lost due to completion of reactions on component i

concentration-dependency of reactionj acting on component i

original mass of material in an infinitesimal control volume

concentration-dependency of reaction acting on species s

final mass of component i

original mass of component i

order of reaction acting on component i

order of reaction i acting on component i

original sample mass for experiments

sample mass measured at time t

real gas constant

time

absolute temperature

specimen volume

mass fraction of component i

mass loss metric for component i

mass loss metric for reactionj acting on component i

total mass lost from control volume

normalized mass loss for sample used in tests

normalized mass lost from control volume

mass lost from component i

total mass lost from volume V

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Polymer matrix composites are being increasingly used in applications

where they are exposed to harsh environmental conditions such as high

temperatures, thermal cycling, moisture, gases, oils and solvents. Exposure

to such environments leads to degradation of composite materials, potentially

affecting the structural integrity and useful lifetimes of composite structures.

Some of the well-known aerospace applications of polymer matrix composites

(PMCs) include engine supports and cowlings, reusable launch vehicle parts,

radomes, thrust-vectoring flaps and thermal insulation of rocket motors.

The increasing demand for such applications has led to extensive

efforts for the development of materials which have upper use temperatures

in excess of 150'C. These materials should be able to withstand a wide range

of temperatures without significant reduction in their mechanical properties,

be chemically resistant to the environment and exhibit low mass loss at

extended aging times at their upper use temperatures.

The behavior of PMCs exposed to high temperatures for extended

durations is not well understood. A variety of effects are observed on matrix

materials, including specimen mass loss, specimen shrinkage, the

development of a severely degraded surface layer, formation of voids, the

development of surface microcracks, and the degradation of mechanical

properties. The problem is further complicated by the anistropic nature of

composite materials. The fiber/matrix interface provides additional sites for

10

both degradation and the formation of cracks.

Composite laminates also

experience thermally (or mechanically) induced interply microcracks in the

matrix material.

These cracks can then provide new pathways into the

interior of the material for the external environment, resulting in more

severe degradation of the laminate as a whole.

The interaction of these

effects during the aging period results in a highly complex, coupled problem

where the identification of individual mechanisms and their contributions

becomes extremely difficult.

As noted by Cunningham [1], design of high temperature structures

would be greatly improved through the development of a model which could

incorporate known quantities such as laminate geometry, material

properties, temperatures and chemical environment, and from these

determine quantities such as the material degradation state as functions of

exposure time and position within the material. A schematic of the desired

coupled analysis which could provide this capacity is shown in Figure 1.1.

The analysis consists of several individual modules which address different

aspects of the problem.

Inputs to the model include the exposure

environment and the applied mechanical loads.

For a comprehensive

analysis, it is necessary to calculate the thermal response, diffusion and

chemical degradation state, and the thermo-mechanical response of the

system. The thermal analysis supplies the diffusion and reaction chemistry

model with the necessary temperatures. This module can then provide the

thermo-mechanical analysis with predictions of the chemical state within the

material.

Results from these analyses can then be used to determine

whether damage (and ultimately failure) occurs. The effects of damage on

material properties, thermal response and the reaction chemistry is

accounted for in an incremental fashion, allowing a truly coupled

11

Figure 1.1

Complete analysis for composite degradation

representation of the problem. Though substantial success has been achieved

in solving different sections of this complex problem, the chemical

degradation has not been adequately quantified.

The current research uses, and hopes to validate, a mass loss (or gain)

metric for the chemical degradation within a polymer matrix composite

material. The extent to which such a metric can be used for developing

predictive capability, assuming that the time and nature of environmental

exposure of a composite are known, is studied. The approach found to be

useful by other researchers [1],[2] consists of using Arrhenius reaction

kinetics to model chemical reactions which occur within the material. Two

types of reactions are considered: thermal reactions which depend primarily

on the duration and temperature of exposure, and oxidative reactions which

also take into account the exposure to oxygen.

The goal of the current research is to establish an analytical

methodology which can be used to predict the degradation states at all points

within a composite laminate as functions of exposure time and environment.

The analysis uses Arrhenius reaction kinetics to model the chemical reactions

which occur within the material.

Multiple, simultaneously occurring

chemical reactions, including both purely thermal reactions and reactions

that depend on diffusing substances, are taken into account. Some of the

earlier work, which formed the basis for this work, showed that the

concentration of diffusing oxygen controls some of the chemical reactions. In

this work we studied only powdered matrix materials so as to decouple the

diffusion effects from

the chemical effects.

A better understanding is

currently needed of these chemical effects.

Experimental studies were carried out to characterize the nature of

chemical reactions, and to determine appropriate models and to quantify

13

them with kinetic reaction coefficients.

Long term isothermal tests for

duration in excess of 200 hours were carried out on finely ground neat resin

powders in both thermal and oxidative environments.

The use of fine

powders, which have very large surface area to volume ratios, effectively

eliminates the diffusion effects which can be seen in finite-sized specimens

[3].

Mass losses were measured for tests carried out at different

temperatures and this data was used to obtain the required chemical reaction

coefficients for the model.

Some of the earlier work had utilized thermogravimetric analyses

(TGAs)

samples.

for measuring the mass loss and mass loss rate on powdered

However, this technique was found to be very expensive for

conducting long term isothermal tests. A new cost-effective technique was

developed for conducting these tests. This technique makes use of an oven

with a temperature controller, a custom setup for holding the sample, and a

sensitive weighing balance to measure the sample mass periodically.

Previous work relevant to the current research and some of the

research which led to this work are described in Chapter 2. This includes

analytical and experimental studies on the degradation of high temperature

PMCs as well as a background on the analytical chemistry used in the course

of this work. The problem statement and approach for the current research

is presented in Chapter 3.

Chapter 4.

The analytical methodology is developed in

Chapter 5 describes the experimental procedure that was

developed to collect data for predicting required material coefficients.

Experimental results, as well as correlation between experimental data and

model predictions is presented and discussed in Chapter 6.

Finally,

conclusions reached on the basis of this work are presented in Chapter 7.

14

CHAPTER 2

BACKGROUND

A number of polymer matrix composites are being used in the

aerospace industry for high temperature applications.

Most of these

materials are thermosetting resins which can be chemically classified as

bismaleimides and polyimides. These resins have proven to be better than

traditional polymer systems in terms of chemical resistance, ability to

withstand high temperatures, and maintaining structural strength and

integrity. However, documenting the behavior of these materials has clearly

shown that these materials degrade with continued exposure to high

temperatures.

The durability issues related to these materials need to be

well understood in order to use them with confidence in primary structure

applications and to improve the design of aerospace components where they

are currently being used.

Introduced in the early 1970s by researchers at NASA Lewis Research

Center, PMR-15 and other polyimides are among the most widely used in

high temperature applications.

These materials exhibit the required

mechanical properties and thermo-oxidative stability [4], [5], [6].

While

PMR-15 has been used in continuous service at 500 to 550F, some of the nextgeneration materials withstand continuous service of 600 to 700F with

excursions to 800F and beyond.

Most of the experimental work carried out to improve the

understanding of these materials has focused on the collection of

experimental data, with the idea of creating a database of the effects of

15

extended exposure to high temperatures. Some of the recent work has tried

to build empirical modes for correlating the degradation effects with changes

in material properties such as strength and weight. There is only a small

amount of work which has tried to quantify the phenomena with the aim of

building accurate analytical models.

Most of the analytical work has led to the building of case-specific

quantitative models and only a very limited number of mechanism-based

models [1], [7]. These mechanism-based models were successful in capturing

some of the degradation phenomena.

However more work is needed for

developing predictive capability based on these mechanism-based high

temperature degradation models.

Some of the relevant experimental studies and analytical work is

reviewed in this chapter. Studies in the area of polymer chemistry are

discussed in order to give adequate background for this work, which focuses

on quantifying the reaction mechanisms.

2.1

PREVIOUS EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES

The extensive experimental data on high temperature degradation can

be broadly classified into three categories - effects of aging on neat resin [8],

[9], bare fibers [10], [11], [12], [13] and composite materials [4], [14], [15],

[16].

Mass loss, shrinkage, and changes in thermal, mechanical and

viscoelastic behavior have been reported. Limited correlation exists between

individual studies.

A study by Bowles [9] on the effects of aging on neat PMR-15 resin

revealed that several coupled mechanisms proceed simultaneously in the

early stages of degradation at elevated temperatures in air. Samples exposed

for up to 3000 hours at temperatures ranging between 288 0 C and 343°C

16

exhibited mass loss, specimen shrinkage, the formation of a distinct surface

layer, development of surface microcracks, and the degradation of mechanical

properties. Mass loss occurs throughout the duration of the aging periods

observed, and in the presence of oxygen results in the formation of a

distinctive thin layer on the exposed surfaces of the polymer. Voids develop

within the surface layer and increase in size and density over time, acting as

starter points for cracks which grow from the exposed surfaces.

The

similarity between the observed surface layer growth rates and mass loss

rates suggests that degradation-induced mass loss primarily occurs within

this thin surface layer, while the core of the material is relatively protected

from oxidative degradation. This suggests that diffusion of environment into

the material plays a key role and is coupled with the chemical degradation

phenomenon.

Similar investigations on the effects of aging at elevated temperatures

on bare fibers have also been conducted.

Bowles [12] found that extended

exposure in air resulted in mass loss from graphite fibers. Data from this

study suggested that carbon fibers such as Celion 6000 consist of a layered

microstructure which has a relatively non-porous outer skin surrounding a

porous core. As the outer layer degrades the environment gains access to the

inner, porous core, resulting in an acceleration of the degradation process.

This effect was also noted by Wong et al. [13] in a study on the thermooxidative stability of IM6 fibers in air. In contrast, fibers in composites are

protected - virtually no surface area is exposed to the environment and no

mass loss is observed [11]. This suggests that adequate quantification of the

matrix degradation is important for studying composite behavior at high

temperatures as the fibers will not be exposed to environment in most cases

where such materials are used.

Unidirectional

demonstrate

composites

similar

degradation

mechanisms to neat resin, although the mass loss is less severe. Mass loss

appears to be dependent on the matrix volume fraction [14], suggesting that

preferential degradation of the matrix takes place. A study on the effects of

different aging environments on the mass loss from unidirectional graphitefiber/PMR-15 composites recorded significant differences in the mass loss

behavior in inert and oxidative atmospheres [4].

Mass losses in inert

atmospheres asymptotically approached stable values over a period of time at

each of the test temperatures. The majority of the mass loss occurs within

the first few hundred hours of aging and appears to be a bulk mechanism,

depending only on specimen volume. After the first 150 hours of aging, mass

losses from the specimens at each of the aging temperatures have essentially

reached their final values, which increases with exposure temperature. This

behavior suggests that only the initial portion of the mass loss curves reflect

thermally activated processes. In contrast, specimens exposed to oxidative

atmospheres will continually lose mass over the entire aging period. Notably

higher mass loss rates are demonstrated in air than in an inert atmosphere

at the same temperature. Aging in oxidative atmospheres always results in

the formation of degraded surface layers.

As aging time is increased, a

distinct layer of degraded matrix forms at the surfaces and advances into the

composite [15]. This layer growth is similar to that observed in neat resin [9].

Scola and Vontell [16] measured the flexural and shear properties of graphite

fiber/PMR-15 composites, isothermally aged at 316 0 C for periods up to 2000

hours, for a number of different fibers. SEM analysis of fractured surfaces

was carried out and optical micrographs of cross-sections were taken. They

observed that composites with high initial shear strength exhibited the

greatest resistance to reduction in shear strength. They did not hypothesize

18

the possible cause of this behavior. These data seem to suggest that the

fiber/matrix interaction played a role in the degradation of the composite

shear strength.

The influence of the fiber reinforcements on thermo-oxidative stability

has been addressed by several research efforts [10], [11], [14] in trying to

explain the accelerating effect of exposed graphite fiber ends on mass loss

rates in composites.

These researchers recorded different behavior in

composite materials with different fiber reinforcements.

The mass loss

behavior was blamed on the effects of impurities in fibers; which in turn

allowed fiber degradation, exposing greater matrix surface are to

degradation. The most thermally stable fibers do not necessarily result in

the most stable composites, and in some cases result in the least thermooxidatively stable configurations [12].

2.2

POLYIMIDE CHEMISTRY

The degradation behavior which has been observed empirically is

dependent primarily upon the chemistry of the matrix material. The PMR-15

material considered in the course of this work is chemically quite complex.

PMR polyimides are addition-type thermosetting polymers prepared by the

polymerization of monomer reactants (PMR). Resin solutions consist of three

individual monomers - a nadic ester (NE), the dimethyl ester of 3,3',4,4'benzophenotetracarboxylic acid (BTDE), and 4,4'-methylenedianiline (MDA)

dissolved in methanol.

When these monomers are combined in a

2.000/2.087/3.087 molar ratio respectively, the formulated weight after

imidization, but before crosslinking, is 1500. Resin of this composition is

designated PMR-15 [17] . The chemistry of the formation of this building

block is quite well understood [18] , however the chemistry involved in the

19

polymerization and later cross-linking of the material is still subject to much

debate with no definitive answer as yet available [8], [19].

The chemistry

involved in the degradation of this and other related systems is under

investigation but it is not yet understood to a level which would allow definite

conclusions to be drawn and predictive calculations to be made.

Evidence suggests that cross-linking within the material is not

complete at the end of the post-cure period, and hence one aspect of the aging

process is the completion of cross-linking reactions. Studies have linked this

increase in cross-link density within the material to the initial increase in

material properties such as the glass transition temperature and compressive

modulus [2], [20].

The fully cross-linked material is subject to both oxidative attack and

thermal degradation at a variety of sites, both in the cross-links and in the

main polymer chain itself at a variety of vulnerable links [21]. The mass loss

over extended aging times is attributed to the degradation of the nadic ester

and MDA components of the main polymer chain while the BTDE component

remains relatively unaffected [22]. The nadic ester appears to be the most

vulnerable to oxidative attack and is thus the weak link in the thermooxidative stability of these materials, with an increase in the nadic ester

content in the PMR formulation resulting in a decrease in the thermooxidative stability of the compound [23]. PMR formulations using the MDA

component demonstrated lower mass loss and higher material property

retention than PMRs formulated using more a stable monomer in place of

MDA. This effect has been attributed to a synergy between the MDA/NE

components which provides sites vulnerable to oxidation in the PMR polymer

chain.

These sites promote weight-gaining reactions (such as carbonyl

formation and thermo-oxidative cross-linking) in surfaces exposed to air,

20

resulting in the polymer possessing a higher thermo-oxidative stability as a

whole [21].

PMR-II-50, also developed at NASA is formulated with a hexafluorodianhydride (the diester thereof, 6FDE) instead of BTDE, for increased

thermo-oxidative

stability in the prepolymer

backbone, and para-

phenylenediamine (PPDA), replacing MDA. Prepolymer molecular weight is

higher at 5000. This results in a 50 to 100F increase in the thermal stability,

with some sacrifice in glass transition temperature due to cross-linking [5].

A great deal of mechanistic information concerning polyimidie

degradation has been ascertained from analysis of the degradation products,

both volatile off-gases and solid residues.

The most prevalent products

evolved during thermolysis of a polyimide are CO2, CO and H20.

At

temperatures below about 350 0 C, C02 is the predominant gaseous byproduct. Above 350 0 C, CO evolution commences and becomes pre-dominant

above 4000 C. The compositions of the volatile degradation products produced

in air and nitrogen are qualitatively similar although rates of their formation

are much greater in air [24].

Releases of larger fragments of the polymer

may follow. In an inert atmosphere such as nitrogen, approximately 60% of

the initial mass of the polymer will remain as char up to 800 0 C. In air, the

more aggressive nature of the environment results in all of the mass being

eventually consumed at these temperatures [25].

While the basic theory

behind the chemistry of this degradation behavior is currently receiving

considerable attention, the efforts in this area to develop a more complete

understanding of this phenomenon remain too diverse to allow the

development of a definitive model of the mechanisms which occur. A more

focused research effort is required for achieving this goal.

2.3

PREVIOUS ANALYTICAL WORK

The confounded nature of experimental data due to the coupling of

various physical effects, and the complex nature of PMR-15 chemistry,

suggest the use of semi-empirical methods for modeling the degradation

behavior. Various physical effects (e.g. diffusion vs. chemical reactions) can

be studied by planning a careful set of experiments that decouple the physical

effects.

The chemistry has proven more difficult.

Reasonable modeling

success could be achieved, without a complete understanding of the

underlying chemistry, if a metric can be developed for quantifying the

degradation.

Attempts have been made to analyze and model various aspects of this

problem. Mass loss rates have been empirically fit to Arrhenius rate curves

[3].

Arrhenius rate kinetics represent an important, established method of

reporting and comparing kinetic data.

The Arrhenius rate equation

expresses material conversion/degradation rate as a function of both

temperature and conversion state. The true versatility of this model lies in

the generality of the conversion-dependence function used in the rate

equation, allowing a large variety of experimental rate measurements to be

modeled in this manner [1]. This type of approach provides a simple means

to model the stability of different systems but is useful only for comparative

purposes if data is not collected and reduced in a rigorous manner. Other

degradation models such as Coats/Redfern,

Ingraham/Marier, and

Horowitz/Metzger have also been fit to mass loss rate data [25].

These

models are less general than the Arrhenius form, placing specific

assumptions on the mechanisms which are being modeled. As such they are

less versatile than the Arrhenius approach and are more commonly used as

methods for comparing the stability of similar polymer systems subjected to

22

isothermal exposures than for determining kinetic parameters for predictive

modeling.

More sophisticated models have combined modeling of the diffusion of

oxygen into the material with chemical reaction rate equations to predict the

mass loss and growth of degraded surface layers.

In many such cases

effective diffusion coefficient models are used [26] where an apparent

diffusivity is found by fitting to experimental mass loss curves for a

composite.

Models of this kind allow the anisotropic nature of the

degradation to be simulated but offer little insight to the true physics of the

problem, effectively smearing many possible mechanisms together into the

observed global effects.

Hinkley and Nelson [27] conducted tests on unidirectional LaRCTM-160

and PMR-15 graphite composite for up to 25,000 hours. They used Arrhenius

plots as empirical fits to obtain ranges of activation energy in a temperature

band of 160-180 0 C.

They were able to obtain reasonable lifetime

extrapolations but did not succeed in capturing the underlying degradation

mechanisms.

Nam and Seferis [28] developed a generalized methodology for

composite degradation based on two elementary reaction mechanisms, hence

allowing for both reaction and diffusion controlled degradation mechanisms.

Several independent reaction mechanisms may be accounted for through the

use of weighting factors. These weighting factors assign certain proportions

of the overall mass loss to individual reactions, each with its own set of

kinetic parameters, and thus allow a variety of complex chemical degradation

processes to be modeled.

2.4

RECENT WORK

Most of the tests of this material exposed to a high temperature

oxidative environment are difficult to interpret because of the coupled nature

of the various degradation mechanisms and the non-uniformity

degradation.

of

Tests are accelerated using temperatures and/or pressures

higher than test conditions. However, the scaling factors associated with

such tests are not well understood. It is not clear, for example, that diffusion

and/or different chemical reactions will scale with temperature in the same

way.

Models which can calculate [29] degraded composite laminate

properties and behaviors based on known degradation states within the

material have been developed.

However, these models require accurate

degradation and diffusion information, and require careful verification at all

levels before they will be useful for predictive calculations.

The understanding of diffusion has substantially improved in the light

of recent work. Cunningham [1] recorded the formation of degraded surface

layers as functions of exposure time using photomicrographs at different

temperatures.

Geometry effects in the neat resin, and anistropic diffusion

effects in the composites, were identified using specimens with different

aspect ratios. The diffusion coefficients were calculated using this data.

The chemical degradation, though well understood, has not been

accurately quantified due to the complex degradation chemistry of PMR-15.

Thermogravimetric analyses (TGAs) were conducted on powdered specimens

in nitrogen and air to separate the thermal reactions from the oxidative

reactions. Tests were also carried out in oxygen to understand the effects of

oxygen concentration on the degradation process. All these tests were carried

out on powdered specimens to decouple the diffusion effects from the

24

chemical effects.

This work suggested that thermal reactions are made up of a spread of

a large number of low mass fraction reactions, although the behavior at

higher temperatures can be approximated using two effective Arrhenius

reactions.

These reactions die out rapidly as the temperature is lowered

towards the use condition and so it may not be necessary to capture the

behavior of these reactions with great accuracy.

Oxidative reactions are extremely active at test temperatures, and are

also of concern at use temperatures.

These reactions are concentration

dependent and appear to consist of multiple reactions which have different

rate and concentration dependencies.

The confounded nature of these

reactions makes it difficult to quantify the mass fractions on which they act.

These reactions dominate the low temperature behavior and so an accurate

representation of their behavior is needed. Cunningham [1] used high rate

dynamic TGA tests to extract a preliminary set of modeled chemical

reactions, but accuracy was limited, and extrapolation to use conditions was

found to be unfeasible. The use of a test program that used large number of

isothermal TGAs along with very low rate (below 1°C. min.) dynamic heating

tests was recommended.

Isothermal TGAs on powdered specimens in nitrogen, air and oxygen

[30] yielded activation energies in air which were approximately one-half of

those in nitrogen, indicating that significantly less energy is required for

oxidation as opposed to thermal degradation. Comparison between tests in

air and oxygen have revealed a strong effect of relative oxygen concentration

on reaction rate, with rates being greatly accelerated with increasing oxygen

concentration. However, only comparative data was detailed in this study,

data was not reduced to a set of kinetic coefficients which could be used in

25

analytical models.

Another way of attacking this problem is the simultaneous use of two

or more techniques focused on studying the chemical phenomena. Liau et al

[31] studied a organic polymer resin called Poly(Vinyl Butyral). Weight loss

curves were fitted to an Arrhenius type equation and each reaction was

identified from its major evolving gas. The amount of gases evolved were

measured using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry (FTIR). However,

data from FTIR will be difficult to interpret in the case of polymers like PMR15, in which multiple reactions lead to the formation of the same byproducts

such as CO2, CO and H20.

Jordan and Iroh

[32] used gravimetry, differential scanning

calorimetry (DSC) and FTIR to study the isothermal aging of partially

imidized LaRC-IA polyimide resin. Qualitative information can be obtained

from spectral assignment of intermediate and final reaction products, while

quantitative evaluation of the spectra recorded in a predetermined time

interval provides the basis for the determination of reaction kinetics. The

time dependent intensity changes, measured at different temperatures

provide the data used to determine the reaction kinetics.

The authors

collected the relevant data but did not demonstrate its use for obtaining the

reaction constants.

Another factor left untouched in most of the other work is the effect of

fabrication parameters on the degradation process.

Weisshaus and

Engleberg [33] studied ablative composites used as thermal active insulation

used in rocket nozzles. They measured failure mode and tensile strength at

temperatures

from ambient to 9000 C for samples which had been

manufactured by the same process, but with different levels of forming

pressure and heat treatment. This study suggested that fabrication method

26

can have an impact on the degradation level because it can influence the

chemistry by leading to different levels of imidization in the polymer.

It is clear that the need for a more accurate kinetic reaction model still

remains. The degradation behavior at use temperatures (150-250'C) needs to

be well understood.

The quantification of oxidative reactions is more

important than that of thermal reactions as material is exposed to air when

in use, and also because their effects outweigh those due to purely thermal

reactions.

CHAPTER 3

PROBLEM STATEMENT AND APPROACH

3.1

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The focus of this research is to develop a model of the chemical

degradation of a polymer matrix composite such that, given the external

chemical environment and temperatures throughout the laminate, laminate

geometry, and ply and/or constituent material properties, and the

concentration of diffusing substances throughout, we can calculate the

metrics of chemical degradation, as functions of time and position throughout

the laminate.

3.2

APPROACH

The approach consists of both analytical and experimental work. The

analysis provides insight into the physical mechanisms and can be used for

building models. These models are also useful for interpreting and reducing

test data. The ultimate goal of the analysis is to provide a capability for

predicting composite degradation behavior.

Experiments improve the

understanding of the chemical degradation in service conditions, and allow

the building of an advanced model that eliminates the shortcomings of the

previous models. Long term isothermal tests were conducted at various

temperatures.

The experimental data was utilized for obtaining the

coefficients of the advanced analytical model and provided verification of the

analytical approach. The data, along with the previous work, also provided

28

useful insights for future testing.

3.3

ANALYTICAL TASKS

The analysis comprises a basic chemical reaction model. An Arrhenius

reaction model is used for describing the thermal and oxidative reactions.

Mass loss (or gain) is used as a degradation metric.

The entire mass is

divided into smaller mass fractions, some of which do not react. Each of the

reacting mass fractions is assumed to be attacked by one chemical reaction

which alters the amount of mass remaining after thermal exposure. Three

different reactions are considered. Two lead to mass loss, and one leads to

mass gain. A negative mass fraction is used to model the mass gain behavior

observed during experiments. The analysis includes the temperature range

for which experiments were conducted (150 to 300'C).

The analysis is implemented through the use of an explicit time-step

Inputs to the analysis are the exposure

finite difference computer code.

temperature as a function of time. Degradation states within the material

are calculated as functions of exposure time. The analysis was used to reduce

mass change data from aging experiments on powdered specimens to a set of

chemical reaction constants.

Finally, model predictions incorporating

chemical reactions were correlated with the mass loss data obtained in aging

tests conducted during the course of this research, and also some of the

experimental results from tests on neat resin powder carried out by

Cunningham [1].

3.4

EXPERIMENTAL TASKS

All materials used in the course of this research were manufactured at

the NASA Lewis Research Center.

29

Neat PMR-15 resin samples are

considered. Isothermal tests on powdered resin specimens are carried out in

both inert and oxidative environments.

The use of powders allows the

decoupling of purely chemical effects from diffusion controlled effects. The

inert atmosphere is used so as to provide data for the purely thermal effects.

A new low cost test method is developed, and tests are carried out for a large

variety of conditions, for up to 200 hours. The results, and the correlation

with the analysis, provide insight into accurate methods for determining

aging behavior in this class of materials.

CHAPTER 4

ANALYTICAL METHODS

The basic analytical approach is described in this chapter.

The

chemical reaction model used for quantifying the degradation is explained

here.

The model uses Arrhenius type of reactions to describe the mass

changes in the material. The procedure for reducing test data to obtain the

reaction coefficients, and the method for implementing the model, are

detailed.

4.1

DEGRADATION MODEL

Chemical reactions are used to model the degradation behavior. The

analytical treatment given here is similar to that used by Cunningham [1]

and McManus and Chamis [29]. The reactions are considered to take place

inside an infinitesimal control volume containing a mass mo of matrix

material.

The fibers are assumed to be stable.

The matrix material is

assumed to consist of different components that are available for various

reactions. A mass mi is defined as the mass that would be lost (or gained)

due to the completion of a set of reactions involving component i. A mass

fraction y, is defined as the ratio between the mass of component i and the

overall mass

(4.1)

y = i

m

negative

A

fraction

mass

to

used

is

indicate

o the amount of mass added due to

A negative mass fraction is used to indicate the amount of mass added due to

a weight gain reaction.

A conversion metric a i is used to quantify the

degradation of mass fraction yi. When a, is equal to zero, no degradation has

taken place; when a i is equal to one, the mass fraction is entirely lost (or

gained). The rate at which mass changes from the control volume due to

degradation of component i is

o-

i

dt -

i

yi dt

(4.2)

Note that summation notation is not used here. The total mass change for

component i, over a time period t is given by

t 8dm

Ami = -dt

(4.3)

Finally, the mass change for the control volume is

Am =

Ami

(4.4)

all i

All of the above considers the mass loss at a point within the material,

which is not a measurable quantity. In a finite specimen of volume V, we

measure the total mass change and mass change rate

AM = AmdV

(4.5)

V

d(AM)

d(Am)dV

(4.6)

Finally, in some cases certain mass fractions will not react. A final

mass mf is defined as the sum of the unreacting mass fractions

mf = m o

.yi

(4.7)

tcunreacting

A normalized mass change, which reaches a value of one when all reactions

have completed, is then defined as

Am' =

m o - mf

(4.8)

The conversion metric, a,, is defined here in terms of the normalized mass

change for each component i at any time t

ai =Am/

(4.9)

Ai

mo, - mfi

where moi and mi represent the initial and final masses of component i

respectively.

For weight adding reactions moi= 0, and for weight losing

reactions mi = 0.

Arrhenius reaction kinetics are assumed for the chemical reactions

acting on the different mass fractions.

Reaction rates for each material

component i are related to the conversion metric, a,, and to the absolute

temperature, T, by different and independent functions. A complete kinetic

description of a chemical reaction requires the characterization of both, the

rate (temperature-dependence) function F'(T), and

dependence function F(ai) [6].

the conversion-

Generally, reaction rates increase with

temperature. At high values of ai the reaction rate will typically slow down

due to the decreasing amount of material available to the reaction.

The rate constant F'(T) is a function of temperature only, whereas

F(ai) is some function of conversion, a i. Typically, F'(T) is assumed to follow

an Arrhenius-type expression, and so

F'(T)= kiexp(-Ei

RT

(4.10)

where ki is the reaction rate constant defining the frequency of occurrence of

the particular reaction configuration, E is the activation energy which

represents

the energy barrier that must be surmounted

during

transformation of reactants into products, and R is the real gas constant.

F(a,) is commonly expressed as (1- a,)"' assuming nth-order kinetics, giving

33

= k,(1- ai)" i exp

dt

(4.11)

RT

In cases where the reactions are controlled by the concentration of a diffusing

substance, a modified form of Eq. 4.11 is used

da=k,(l- a)"' cs exp(-Ei

dt

(4.12)

RT

-

where cs is the concentration of the diffusing species and m, defines the order

of the concentration dependency.

All of the expressions derived thus far assume that only a single

reaction acts on each of the mass fractions.

For the general case where

multiple reactions can occur, each mass fraction yi can be attacked by a

number of reactions j.

The reactions rates in, say, an oxidative atmosphere

can then be fully described by

dt

- k i(1- a i )n cmii exp

S.f

(4.13)

RT)

where cS is the concentration of the diffusing oxygen. Again, summation is

not implied here. The reaction rate constant k, , activation energy E1j, and

reaction order nij are needed to fully characterize each reaction. The oxygen

concentration dependence mij is zero for thermal (non-oxidative) reactions,

and must be specified for oxidative reactions. The reduction of mass fraction

of component i is calculated from

dai

daiJ

(4.14)

idt

(4.15)

allj

ai

=

Note that none of the quantities in here are tensors. The notation

employed in these equations was chosen as a convenient method in which to

express the occurrence of multiple, simultaneous reactions.

34

This is the

general form of the chemical degradation model. The specific model used in

this research considered that only one chemical reaction acted on each

component. The additional complexity of multiple reactions acting on each

component was not required to model the observed chemical reactions.

4.2

DETERMINATION OF KINETIC CONSTANTS

No standard method is available in the literature for determining

kinetic constants from mass loss data for isothermal tests.

Reaction

constants for the model were obtained by reducing the data using curvefitting techniques.

The mass loss/gain data collected from isothermal tests in air suggests

that a minimum of three reactions are required to describe the chemical

degradation. Determining the mass fraction on which each reaction acts, and

the three kinetic constants that specify each reaction, is necessary for

completely describing the model. Each reaction is described using three

constants: activation energy E,, order of reaction ni, and rate constant Ki,

where

Ki = kicms,

(4.16)

and cms ' is constant because the oxygen concentration does not change as a

function of time or position.

Observed experimental data, detailed in Chapter 6, indicated the

presence of two reactions acting on relatively small mass fractions and a

reaction acting on a large mass fraction. Once of the small mass fraction

reactions led to mass gain. The mass gain reaction was modeled using a

Arrhenius type of reaction acting on a negative mass fraction. None of the

previous models include mass gain behavior.

35

The small mass fraction

reactions with mass loss (reaction 1) and mass gain (reaction 2) showed

saturation behavior (no more mass loss or gain is seen). The mass fractions

for these reactions were determined using the normalized mass loss/gain seen

at saturation stage.

The large mass fraction for the third reaction was

estimated using a numerical search. After the mass fractions were obtained

the kinetic constants were determined using a curve-fitting procedure in two

steps. The details of this curve fitting procedure are described in section 4.4.

4.3

MODEL IMPLEMENTATION

The model was implemented for an infinitesimal volume subjected to

isothermal heating in air. Three reactions were considered, all of which were

assumed to be oxidative. As the tests were conducted on powdered material

in air, no variation in the oxygen concentration was considered.

conditions consisted of ai= 0 for all three reactions.

Initial

The reaction rate

constant K i as described in Eq. 4.16 was used. E, ni, and K were specified for

each reaction along with time t. The rate of reaction was calculated using Eq.

4.12 and then multiplied by the corresponding mass fraction (Eq. 4.2) to get

the rate of change of mass for each reaction. The rate of mass change for

each reaction was then integrated over time t (Eq. 4.3) and then summed to

obtain the total mass change (Eq. 4.4). Reactions that showed saturation

reached state a,=1 and then the reaction state did not change. All the mass

changes were calculated as normalized mass loss or gain. The model was

implemented using an explicit time-step finite difference computer code

4.4

DATA REDUCTION IMPLEMENTATION

Observation from the experimental data showed the presence of a

minimum of three different reactions. There is a possibility of more than 3

36

reactions being active in this temperature range (150-300'C), however it was

thought that three reactions would be sufficient to model the degradation

behavior observed in these isothermal aging tests.

The coefficients for the three reactions in the model and the mass

fractions on which they act were obtained from the experimental

observations.

We assumed a small mass loss reaction (see 150 0 C), a small

mass gain reaction (see 175-200'C), and a mass loss reaction that affected a

large mass fraction. The saturation behavior seen in 150-200'C test was

utilized for obtaining the mass fractions for the two small mass change

reactions. The large mass fraction for the third reaction was estimated using

a numerical search. No distinction was made between thermal and oxidative

reactions. All reactions were modeled as being of the form

dai = Ki(1-ai)n ' exp(-i )

dt

RT

(4.17)

where K is defined in Eq. 4.16 for an oxidative reaction. In case of a thermal

reaction, K i = k i was assumed.

The three coefficients for each reaction

consisting of rate constant K, reaction order ni, and activation energy E were

estimated using an optimization procedure in two steps. In the intermediate

step, each reaction was modeled using C and n, where

Ci =Ki exp(- i

(4.18)

Each reaction was described as

ai = Ci(1- ai)n '

(4.19)

The degradation state for each reaction was determined using the explicit

time-step finite difference formulation

ai(t + At) = ai(t) + -

(t) x At

(4.20)

where a i = 0 at t = 0.

The reaction state calculated in this manner was

multiplied by the respective mass fraction for all the reactions to obtain the

total normalized mass loss/gain. These results were compared with the data

obtained from experiments and the least squares error was calculated.

Values for Ci and n were obtained by minimizing the least squares error for

each temperature.

This was carried out for data at all the seven test

temperatures (150-300'C in steps of 25°C). The n values were found to be in

a narrow range for each reactions, as expected. The reaction order in the

Arrhenius type of reaction does not change with temperature. The values

obtained for Ci varied a lot because of the strong dependence on temperature.

The MATLAB code utilized for this purpose is given in Appendix A along

with all the other codes used during the course of this research.

In the next step, each reaction was quantified using all the three

coefficients Ki, n, and E i .

The reaction states for each reaction were

calculated using the finite difference formulation from the previous step. The

normalized mass loss (or gain) was obtained as in the previous step.

Estimates of mass change were obtained for all the seven temperatures and

then compared to the experimental data. The least squares error obtained

from comparison with each data set was normalized by the mean mass

change for that temperature. The sum of such normalized least squares error

for all the data sets was used as the error function. This error function was

minimized using a standard optimization tool available in MATLAB (version

5.2).

Constraints were placed on the values of reaction order as per the

ranges obtained in the previous step. This constrained optimization is solved

using the Levenberg-Marquardt method by the optimization tool.

The

coefficients so obtained were used for further comparisons of the model with

data from previous researchers.

CHAPTER 5

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Experiments were carried out to obtain data for the chemical

degradation model described in Chapter 4.

The data obtained from

experiments gave valuable insights into the physics of the problem in

addition to helping obtain the reaction and mass fraction coefficients.

The

new cost-effective experimental method is described along with details about

specimen preparation, the set-up and data collection.

Only neat PMR-15

resin samples were used.

Only neat resin specimens in powder form were used in this

investigation. The test matrices were designed based on recommendations by

Cunningham[1], and the fact that the in-use temperature range for this

material is from 150 to 2500 C. The material is also known to give off noxious

fumes at a temperature of 350'C and beyond.

Cunningham [1] had also

recommended the use of specimens with large surface area to volume ratios

in determining kinetic parameters.

Reaction coefficients estimated from

experiments conducted on finite-sized specimens may be confounded because

of diffusion effects.

Oxidative reactions were shown to be limited by the

amount of oxygen available and hence powdered specimens were utilized for

eliminating the diffusion effects. The test matrices were designed in such a

way as to allow the necessary coefficients to be extracted from the data and

also to provide sufficient data to allow a complete validation of the modeling

approach.

The material systems used in this study was PMR-15 neat resin. All

materials were manufactured at the NASA Lewis Research Center. The

material was initially cured in plates and was then reduced to powder form.

This ensured that the initial chemical state of the material was the same as

that used in real structures. The test matrix used for the isothermal heating

experiments is shown in Table 5.1. Isothermal heating experiments were

carried out on PMR-15 neat resin powder in nitrogen and air. This was done

with the aim of allowing the quantification of the kinetic parameters in both

thermal and oxidative atmospheres without the additional complexity

introduced by diffusion dominated effects.

5.1

MATERIAL MANUFACTURE AND PREPARATION

All specimens were manufactured at the NASA Lewis Research Center

using standard manufacturing procedures developed for the PMR polyimides.

The details of these procedures may be found in [34]. Two PMR-15 neat resin

panels (both 102 mm x 102 mm and approximately 3 mm thick) were used

during this study. After curing, all panels were subjected to a 16 hour freestanding post-cure in air at 316 0 C.

Narrow strips (approximately 5 mm wide) were cut from the neat resin

panels using a clean, sharp knife edge. These strips were then broken into

several small pieces and placed into a standard coffee grinder. To avoid the

problem of plastic shards from the grinder blade casing contaminating the

material ( as previously encountered by Cunningham [1]), a grinder with

metal casing was obtained. A custom steel lid was manufactured for use

instead

of

the

plastic

cover.

Specimens

were

subjected

Table 5.1

Neat ResinA Isothermal Exposure Test Matrix

Atmosphere

Isothermal Exposure temperature

Air

Nitrogen

125 0 C

1

1

150 0 C

1

175 0 C

1

200 0 C

1

225 0 C

1

250 0 C

1

275 0 C

1

300 0 C

1

A

All specimens in form of fine powders.

1

1

to grinding for about five minutes. The grinder was turned off after every

two minutes for about thirty seconds to avoid over-heating the motor. The

powder which was produced in this manner was then sifted through

calibrated sieves to obtain the required grade of powder for analysis. A fine,

light-brown powder was obtained from each sample through the use of this

technique.

Tests conducted by Cunningham [1] had indicated that the

particles obtained through the use of a No. 40 USA Standard Testing Sieve

(425 micron grating) were sufficiently small to ensure that the effects of

diffusion on the weight loss behavior in oxidative environments would be

negligible. All of the powder was sifted through a No. 40 sieve.

All powders produced in this manner were placed in small, unsealed

glass jars into the oven for 2 hours at 125°C to remove any residual moisture.

Due to the large surface area of the particles, the removal of moisture from

the powder is achieved in small amounts of time. This large surface area also

has a secondary effect which is to allow moisture to diffuse very quickly back

into the powder. The neat resin powder was found to be very hygroscopic,

rapidly absorbing moisture from the air upon removal from the oven. The

glass jars were immediately sealed after removal from the oven and the

powder was stored like this until testing.

5.2

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE FOR ISOTHERMAL TESTS

5.2.1 Experimental Set-up

All powdered neat resin samples were aged in a thermal environment

chamber.

The chamber used electric resistance rods for heating and a

maximum temperature of 427°C could be achieved. A stainless steel rack

made using four rods and three rectangular plates with holes, was used to

support the specimens within the chamber. The powdered sample was placed

in an aluminum pan (dia. 35 mm) in the same location close to the chamber

bottom for each test. Internal chamber dimensions were 30.2 cm x 10.2 cm x

10.2 cm (12" x 4" x 4"), and the sample pan was placed at a height of 3" from

the bottom..

A schematic of the set-up is shown in Figure 5.1.

The

specimens were shielded from direct heat radiation from the heating rods and

were heated by fan-circulated air only. The temperature of the chamber was

controlled through the use of an Omega temperature controller.

This

microprocessor-based controller could be programmed to any user-defined

thermal profile consisting of a series of linear segments. A single J-type

thermocouple provided feedback to the controller. The temperature gradient

between the sample pan location and the controller thermocouple was

minimized. Over 100 tuning runs had been carried out in a previous study to

determine the optimum controller tuning settings and feedback thermocouple

location [35]. These settings were not altered in the current study.

5.2.2 Tests in Air

A clean aluminum pan, spatula and pincers were used for each

experiment. This apparatus was cleaned with water and than with methanol

and then dried for 15 minutes in a clean-air hood. A new pan was used for

each experiment. The steel rack and inside of the chamber were cleaned

using a wet paper towel before each experiment. The chamber was then

heated to 125°C and held there for 15 minutes before starting the

experimental run.

- Steel stand

Aluminum pan with sample

Control Thermocouple

Figure 5.1

Schematic of specimen and thermocouple location in thermal

environment chamber (not to scale).

AE 100 Mettler balance with a least count of 0.1 mg was used for weighing

the pan and sample. The clean pan was weighed first, and then a sample of

about 600 mg was placed in it. A spatula was used for removing the powder

from the glass jars. The weighing balance was recalibrated and its leveling

checked before each experiment. The sample pan was moved using pincers

only, and the pincers were cleaned periodically and kept free of dust

throughout the experiment. The pan was placed on the lowest shelf inside

the chamber. The sample was then heated to 125oC and held for two hours.

The pan was removed from the chamber and weighed at the end of these two

hours.

The sample mass obtained from this measurement was utilized

during all further calculations. The temperature was then ramped up to the

test temperature and then held there for a duration in excess of 200 hours.

The sample pan was removed periodically for weight measurements.

The chamber door was opened, the pan was removed, and the door was

immediately closed. The pan was then weighed using the sensitive balance

and then put back into the thermocycling chamber. This procedure lasted

less than a minute. The test chamber temperature dropped because the door

was opened twice during each measurement. However, the test temperature

was restored in less than five minutes due to the large thermal mass of the

chamber. As tests were conducted in excess of 200 hours, and readings taken

with an average gap of six hours (360 minutes) this temperature drop was

not considered in further calculations and the sample was assumed to be at a

steady temperature throughout the duration of the test.

A test was conducted in which a pan with powdered resin sample was

held at 125°C for over 200 hours. No reactions are known to occur at this

temperature and this experiment was conducted to study the extent of

possible scatter and any other sources of error. The weighing balance takes a

few seconds to give a steady reading. This reading can be affected by any

potential moisture absorption during this period. The readings showed a

variation of +1.0 mg to -1.1 mg. Lack of any trend in this data showed that

the sample was not being blown away by the circulation fan and that error

due to sources such as moisture absorption was small (0.2%).

5.2.3 Tests in Nitrogen

Additional parts were used in the set-up for conducting isothermal

tests in nitrogen.

Nitrogen cylinders with 5 PPM impurities were used

during these test. The cylinder was connected to a two-stage regulator. The

maximum pressure of gas in the cylinder was 2000 psi. The second stage had

a delivery pressure from 0 to 150 psi. The gas was then fed to a flowmeter,

which was then connected to a tube.

The gas passed through a

moisture/oxygen trap before reaching the solenoid valve on the thermocycling

chamber. The trap had a specification of 0.5 PPM impurities. A schematic of

the setup used for tests in nitrogen is shown in Figure 5.2. The gas pressure

was maintained 40-50 psi above the atmospheric pressure and the gas flow

was increased (from 596 ml/min. to 913 ml/min.) during the time of sample

removal for weight measurement. The gas was maintained at a pressure to

avoid any air leaking into the chamber during the experiment. The effect of

air exposure during the weight measurements was assumed to be

insignificant. This assumption was found to be incorrect after data from

three different runs was reduced. The details of this error are discussed in

Chapter 6 (Results).

46

Input pressure

up to 2000 psi

Delivery pressure

0 to 150 psi

Figure 5.2

Schematic of atmosphere control system for aging tests in inert

atmosphere

CHAPTER 6

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this chapter the experimental data and the analytical results

obtained from the model are presented. Long term isothermal tests were

conducted in oxidative environment (air) and also in purely thermal

environment (nitrogen). The data from tests in air was reduced to obtain the

kinetic reaction coefficients, which served as input to the analytical model.

The model was correlated with this data.

A combined model, using this

model with parts of the previous model of Cunningham [1] was used for

correlating with some of the previous TGA data.

6.1

LONG TERM ISOTHERMAL AGING TESTS IN AIR

Isothermal aging tests in the oxidative environment were conducted

for temperatures of 125 to 300°C in steps of 25°C. This temperature range

was selected because the service conditions for this material range from 150250°C. The results obtained are presented in the form of normalized mass

loss plotted against time in hours. This data was then reduced using the

procedure described in Chapter 4. A comparison of model predictions using

these coefficients with the isothermal aging data is also presented.

6.1.1 Experimental Data

All tests were conducted on powdered specimens in order to separate

the diffusion effects from the reaction chemistry. Each sample was heated at

48

125"C for two hours before it was heated to the test temperature and held

there for a duration in excess of 200 hours. The sample mass measured at

the end of two hours of heating was used as the original mass.

The

normalized mass loss Am,(t) at time t was calculated using

Amn(t) =

- M(t)

Mo

(6.1)

where M o is the original sample mass, M(t) is the sample mass measured at

time t.

A long term isothermal aging test was carried out at 125°C to estimate

the experimental error. No reactions are known to occur at this temperature

and this test was conducted to study the extent of possible scatter and any

other sources of error. The sample was removed from the thermocycling oven

for mass measurement periodically.

atmosphere during this measurement.

The sample was exposed to the

The actual process of taking a

measurement took a few seconds, mostly to allow the weighing balance to

give a steady reading. The reading can be affected by any potential moisture

absorption during this period.

For a sample mass of about 600 mg the

readings showed a variation of +1.0 mg to -1.1 mg. The normalized mass loss

results obtained from this test are given in Figure 6.1. Lack of any trend in

this data showed that the sample was not being blown away by the

circulation fan and that error due to sources such as moisture absorption was

small (0.2%).

Experimental results obtained from tests at different temperatures are

shown in Figures 6.2 to 6.8. The test conducted at 150"C clearly shows the

presence of a small mass fraction reaction, see Figure 6.2. After a duration of

about 100 hours saturation behavior was seen (no further mass loss/gain).

The maximum normalized mass loss value was 7.2 x10 -3 . The mass fraction

49

0.002C

1250C

0

0.0015 S0

0.001C

0.0005

0.000C

0

0

-0.0005

-0.001 C

13

130

0

0

13

13O

131

-0.0015

13

-0.002C

Figure 6.1

0

50

100

150

Exposure Time (hours)

Isothermal aging test in air at 125°C

200

250

0.020

0

O

150 C

0.015F

0

_J

- 0.01C

)

a0

N

E

0.00

o

10

0

0

10

0

z 0.005

0.00(1

0

50

0

13

0 1

100

150

Exposure Time (hours)

Figure 6.2

Isothermal aging test in air at 150"C

200

0.005-

0.0001

c,

1

cn -0.005

N

i -0.010

E

z

-0.015

-0.020-

0

Figure 6.3

200

400

600

Exposure Time (hours)

Isothermal aging test in air at 175°C

800

0.005

0

200 OC

0.000

O

-0.005

-0.010

0lO

-0.015

-0.020

Figure 6.4

12PW

[0113

0

D

1

300

Exposure Time (hours)

100

200

Isothermal aging test in air at 200'C

400

0.030

0.025

[7

225 OC

0

13

0.020

0

-J

0

0

0.015

0

0

0.010

N

0.005

,

0

E 0.005

0

0

z

-0.005

-0.010

-0.015

Figure 6.5

W c

0

13g 13O

IMO0

300

200

100

Exposure Time (hours)

Isothermal aging test in air at 225°C

400

0.160

0.140

cn

(I

0

-Z

CD

0.120

SC3

0

z

250 C

0.100

---

0.080

0.060

E

3

0.040

0.020

t

Ii

o.oo00

-0.020'

Figure 6.6

I

0

200

I

800

600

400

Exposure Time (hours)

Isothermal aging test in air at 250"C

1000

0.160

0.1

0.1

cn

o0

0.1

cn

0.080

N

0.060

E 0.040

0

z

0.020

0.001

-0.020L

0

Figure 6.7

150

100

50

Exposure Time (hours)

Isothermal aging test in air at 275°C

200

0.160

P

3

0.140

300 OC

d:PO6

0.120

db3

0.100

0.080

0.060

F

0.040

/

0.0201

0.00oo

-0.020'0

Figure 6.8

150

100

50

Exposure Time (hours)

Isothermal aging test in air at 300 C

200