(1957) (1959)

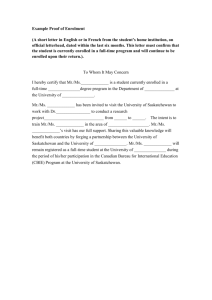

advertisement