Document 10622260

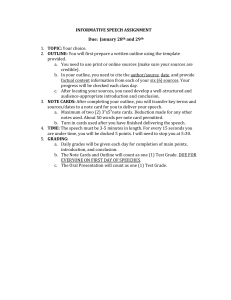

advertisement