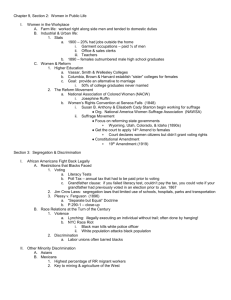

Race v. Suffrage The Determinants of Development in Mississippi

advertisement