An Analysis of Successful Projects and ... Application to the Denver Centerstone Retail Project

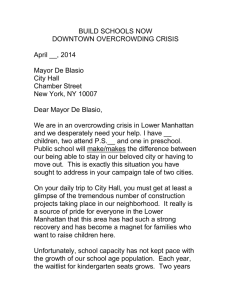

advertisement