VIPS, July 26, 2012 Sam Black A Survey of Climate Ethics + Defense of A Pluralistic ...

advertisement

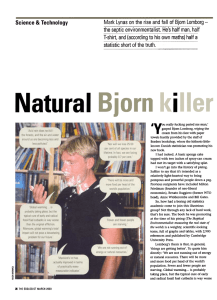

VIPS, July 26, 2012 Sam Black A Survey of Climate Ethics + Defense of A Pluralistic Approach Constrained by A Cautionary Principle Non‐pluralistic, anthropocentric approaches to environmental ethics: The value of the non‐human environment is purely instrumental and derived from its contribution to personal or impersonal human welfare. This includes the view that I resist – impersonal welfare aggregation ‐‐ which holds that: The value of the non‐human environment is constituted by the sum of the human desires. Pluralistic approaches to environmental ethics: Aspects of the non‐human environment have non‐instrumental value, or value that is not derived from human welfare in addition to human welfare. The Plan: I begin with anthropocentric approaches to climate ethics and then explain why I favor a pluralistic proposal + a cautionary principle. Background Assumptions Climate Ethics is inseparable from environmental ethics and ethics more generally. The reason to preserve the earth’s climate at a given temperature is purely instrumental. It is valuable because it is a means to some other valuable end. Climate change on Pluto does not matter. Climate Ethics differs from Climate Economics Climate ethics holds that there is a moral duty to promote impersonal human welfare and possibly non‐anthropocentric values. It rejects the notion that resources should only be allocated to persons with effective demand on the ground that this principle conflicts with moral duties to: the poor future generations individual non‐human animals entire species, abiotic features of the environment, etc. N.B. It’s possible that climate ethics and climate economics converge on policies, but for different reasons. I. Anthropocentric Approaches 1. The Principle of Utility e.g. Dale Jamieson, Bjorn Lomborg, Derek Parfit Pros: • Captures the intuition that the interests of all human beings – including future people – count as equals. • It does not matter whether climate change is caused by human beings or not. Cons: • It may justify very few restrictions on climate change. 1. A CBA of Impersonal Utility vs Climate Conservation is Special Ex. Bjorn Lomborg ‐‐ It’s the World’s Poor Stupid; There’s Nothing Special about Climate Issues Two reactions to Lomborg. 1 A. Empirical scientists contend that Lomborg’s CBA – his facts and calculations ‐‐ are badly flawed and his policy recommendations would consequently not use resources in ways that do the greatest good. B. Philosophers have roundly condemned Lomborg on less empirical grounds including: i) Pragmatism: Even if he is right about the optimal policy for the least well off members of the world, people are more willing to pay to reduce climate than they are to help the world’s poor. ii) The Values in his CBA: see below. iii) An argument via the moral principle that ‘Harming is Much Worse Than Failing to Aid’: a) The moral duty not to harm people is much weightier than the moral duty to help people. b) Wealthy countries have not caused global poverty and the harms flowing from it (disease, ignorance, hunger, ect.). c) Wealthy countries have caused climate change. (Lomborg’s critics assume this.) d) Therefore, the moral duty to mitigate the effects of human caused climate change is much weightier than the moral duty to help the world’s poor. Assessing (a): The Plague Example Suppose a plague arose from a random bacterial mutation that will kill 1 billion people unless they are each given a $50 vaccine (Cost $50 billion); and suppose that spending $50 billion on climate change would save 100 million people. Because I reject (a), I reject Rights‐Based approach to Climate Ethics. But some philosophers reject (b) appealing to the effects of unfair trade laws, etc.; their argument could support Lomborg’s approach – a CBA approach to repairing rights violations. 2.A Standard Human Rights Approaches – e.g. Simon Caney There is a moral duty to mitigate the violation of 3 human rights resulting from human‐ caused climate change: 1. The right to life 2. The human right to health 3. The human right of subsistence Pros: • There is widespread international consensus regarding the existence of some human rights. Cons: • Worries about the principle that ‘Harming Is Much Worse than Failing to Aid’. • Depends on proving a causal link between human activities and some or all effects of climate, raising issues about the allocation of moral responsibility. Analogy: suppose the run off from our field creates an algae bloom, and Smith succumbs to liver illness when he bathes in the lake, but his heavy liquor consumption, and the metals in the local water supply also cause Smith’s death. • The list of rights should be amended to include the right of a people to sustain their culture – a right that is implicated by climate change because some cultures are highly dependent on traditional economies; those economies will be destroyed by climate change. 2.B An Alternative Rights‐Based Approach: Lockean Commons Theories (e.g. Peter Singer) Singer: The atmosphere is a commons. Its value is degraded when people pollute it – in the same way that the value of the commons is degraded when land is taken from it. It’s a condition for having the right to use the atmosphere that others have a similar right to use an atmosphere with the same value. Singer claims that each person consequently has a quota to pollute and must buy the 2 pollution rights of others if they wish to exceed that quota. This entails large financial transfers from wealthy to poorer individuals. Pros: • Captures the idea that all humans own the earth in common (without adopting the controversial utilitarian idea that the welfare of all people matters equally) • May be palatable to people who believe they are only responsible to repair rights they have violated. • Doesn’t require proving a causal link between human activities and harm – since the GHG emissions themselves rather than the harms that flow from them are the basis for rights violations. Cons: • The Indulgence Analogy: If polluting is wrong because it harms others, then people should not be allowed to harm others simply because they can pay for the privilege. (Robert Goodin compares it to the debate over papal indulgences.) • Revised estimates of the period for CO2 breakdown may suggest that there is no further quota to emit GHG’s, which would eliminate the market for buying quotas. II Beyond the Anthropocentric CBA Approach 1. The Cautionary Principle (e.g. Henry Shue, The Economist) Shue argues that in decision contexts where the consequences are large, the relevant data is uncertain, we should err on the side of caution and seek to avoid the worst‐case scenario. Ex: In addressing a bird flu epidemic we should quarantine more than necessary (Shue) Ex: Fracking ‐‐ The current debate over natural gas production via fracking pitting those who urge caution against those who favor economic gains, or reduction of GHG’s from burning coal. Pros: Emphasizes the incredible complexity of a CBA approach and uncertainties arising from: • Climate science • The valuation of the interests of individual members of future generations (e.g. welfare = preferences vs objective interests) • The valuation of the impact for individuals of the loss of their culture esp. traditional societies • Arguably people behind a veil of ignorance would choose this decision principle if they don’t know their position in society and state. 2. Pluralistic or Non‐Anthropocentric Views A CBA is further complicated by non‐anthropocentric sources of value. Claim: We already do believe there are many non‐anthropocentric sources of value, but we’ve failed to examine the implications of our beliefs for non‐human nature. A. Individual Animal Welfare Pros: • The various attempts to explain why all members of the human species have moral rights fail to show that some or all non‐human animals lack moral rights. Cons: • The rights of individual animals may conflict with the preservation of other species, and bio‐diversity more generally. Hypothetical Example: Vancouver Marmots vs Rats 3 B. Aesthetic Value in Nature e.g. Eliott Sober, Marlene Russow, Eric Katz Aspects of the non‐human natural world are like great works of art in having a value that is not reducible to the preferences or welfare of individual persons) Analogy: existing bio‐diversity is like being custodian of museums filled with priceless antiquities and old masters, for ourselves and future generations. Pros: • Explains why conserving certain existing species – e.g. polar bears, great forests ‐‐ is valuable. • Explains why conserving abiotic features of the environment is valuable. • We are already committed to conserving aesthetic value, though biased toward human culture. In 2009‐10, the three levels of government spent $9.6 billion on culture, excluding transfers between different levels. http://www.artsresearchmonitor.com/article_details.php?artUID=50765 C. Non‐Instrumental Cognitive Value: The destruction of natural environments, and the human cultures and languages they sustain, is a disvalue because it contributes to the loss of knowledge. Analogy: Loss of existing species and cultures is like the destruction of a particle accelerator. The appeal to cognitive value differs from the claim that plants are important to conserve since they may yield human medications. Pros: • We value knowledge for its own sake. Spending on scientific research and development in the 2009 Federal amounts to more than $10 billion in the 2009– 2010 fiscal year (from total Federal expenditures of $276 billion). D. Heritage Value: Analogy: The destruction of the forests and glaciers is like turning Parliament into Disneyworld, or allowing the building to rot away rather than paying maintenance. Postscript: Discussion at the VIPS meeting persuaded me that the correct approach to climate ethics rejects the view that CBA provides an algorithm or decision‐procedure for evaluating policy. This is not to say that CBA is not valuable in contexts. But the ultimate decisions about which policy should be adopted requires the exercise of judgment (e.g. by politicians or a court) to weigh conflicting values. III More Radical Approaches Some philosophers claim that climate ethics point to the need for massive revisions to “Individualistic Western Ethics”: i) A new theory of value that contains holistic elements that include the value of species (Marlene Russow, Elliott Sober). This is not that radical. ii) A new theory of moral responsibility that includes collective moral responsibility via an argument the principle that people are not morally responsible for making only very small contributions to processes that are very harmful (Dale Jamieson, Walter Sinnott‐Armstrong). Reply: flushing unused paint down toilets. iii) A new theory of individual personal identity that blurs the distinction between people and nature (e.g. David Suzuki). Reply: I hope I believe this too when I’m 75 too. 4