Document 10610550

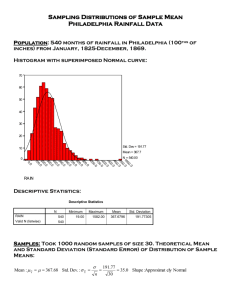

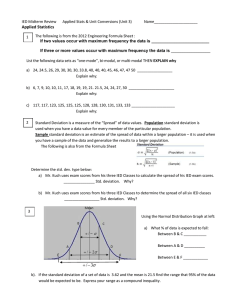

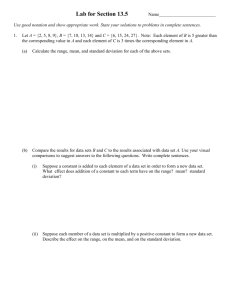

advertisement