Document 10607695

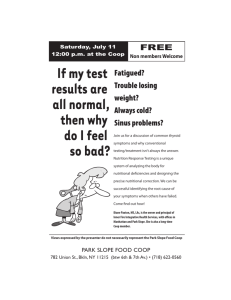

advertisement