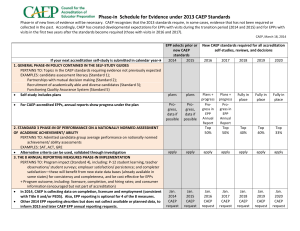

CAEP ACCREDITATION STANDARDS as approved by the CAEP Board of Directors

advertisement