DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF A ... TUNING FORK GYROSCOPE

advertisement

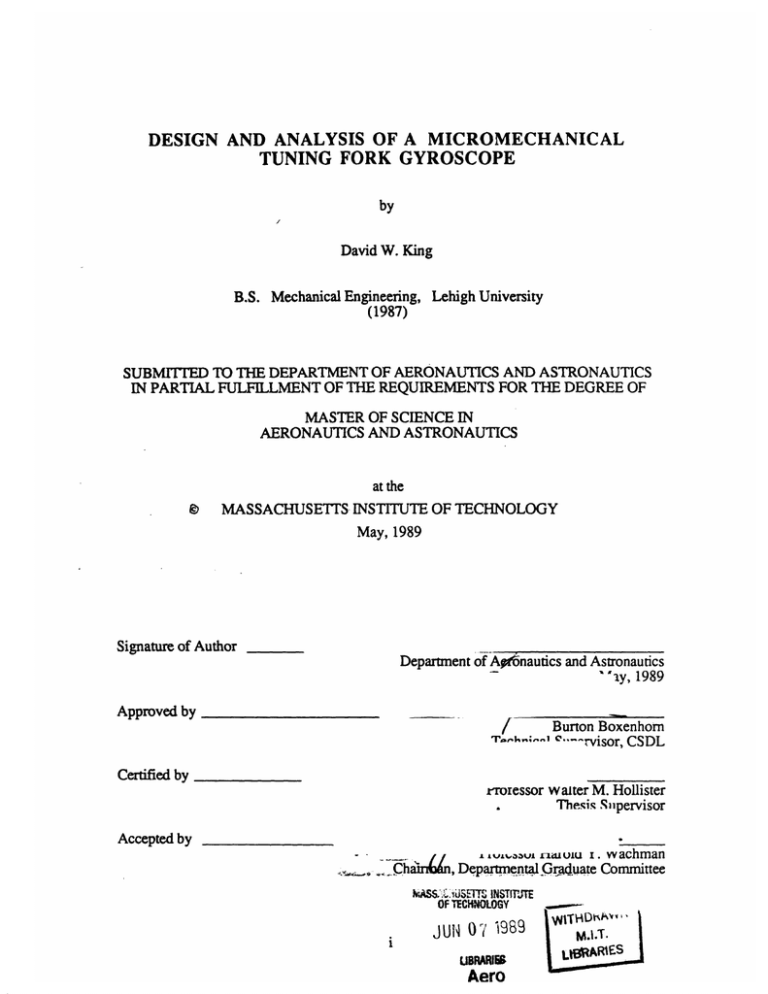

DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF A MICROMECHANICAL

TUNING FORK GYROSCOPE

by

David W. King

B.S. Mechanical Engineering, Lehigh University

(1987)

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN

AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS

at the

©

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

May, 1989

Signature of Author

I-Department of A06nautics and Astronautics

"%'y, 1989

Approved by

wr

Certified by

/

Burton Boxenhorn

-,4

,..I.rvisor, CSDL

rroiessor waiter M. Hollister

a

The.si.s Supervisor

Accepted by

-_

S•...h..

MASS.&ii•

.,,,aL

JiiunuwIsu i. wachman

DepartmentalGGrduate

.in,

Committee

1'•E.

ir INSTITUTE

Ac IrvrulmnlAUt_%

yr

IE~Ini7tJLUU;I

JUli 0,-9'1989

UBRARIS

Aero

DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF A MICROMECHANICAL TUNING FORK GYROSCOPE

by

David W. King

Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on May 12, 1989 in

partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in

Aeronautics and Astronautics

ABSTRACT

This thesis investigates the feasibility of a micromechanical tuning fork as an angular

rate sensor. The gyroscopic effect of a tuning fork, which is caused by the oscillating mass

moment of inertia due to the vibrating tines, is described and demonstrated by a simple

model. The gyroscopic response to an input rate about the longitudinal axis between the

tines is described by a second order, linear periodic (LP) differential equation which is

derived by Hamilton's variational method. If the periodic terms in the equation of motion are

neglected, the gyroscopic output is shown to be oscillatory in phase with the vibrating tines

and linearly related to the input rate, the system quality factor, and the mechanical gain of the

gyroscope. The mechanical gain is the ratio of the oscillating component of the mass moment

of inertia about the input axis to the nominal component.

The periodic terms in the equation of motion are not negligable for a lightly damped,

high frequency micromechanical system. A sufficient condition for stability of the LP system

is derived from the properties of the Mathieu Equation. The stability condition is specified in

terms of the product of the system quality factor and the mechanical gain, and it is checked by

applying Floquet Theory. The response of the gyroscopically forced LP equation is solved

numerically and also estimated by a Fourier Series solution. Both of these solutions

correspond with the estimated linear response within the stability region.

Mathematical models are derived for the electrostatic driving force between the two

fork tines, the variable capacitance sensing of the gyroscopic rotation, the stiffness properties

of the structure, and the air damping torque. In addition, possible error sources are analyzed

including cross-axis sensitivity, external forces and vibration, unbalance torques, motorsensor coupling, amplifier noise, and Brownian Noise. The system mathematical model is

implemented into a computer program and a baseline design configuration is obtained which

is compatible with micromachining processes. The predicted performance of the baseline

design is shown to be competitive with the double gimbal micromechanical gyroscope

currently being developed.

Thesis Supervisor:

Title:

Dr. Walter M. Hollister

Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank Burt Boxenhorn of the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory who is

responsible for the original idea of a micromechanical tuning fork gyroscope, and who has

stimulated many of the ideas presented in this paper through his pioneering work on

micromechanical inertial instruments. I must also extend thanks to my advisor, Professor

Hollister, who provided invaluable guidance and support throughout this project. Also, I

would like to express gratitiude to my colleagues who offered assistance, with special thanks

to John Connally, Doug Loose, and Norm Wereley. Finally, I am indebted to The Charles

Stark Draper Laboratory for providing generous support of the Micromechanical Instruments

project.

This report was prepared at the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. under internal

funding.

Publication of this report does not constitute approval by the Draper Laboratory or the

sponsoring agency of the findings or conclusions contained herein.

I hereby assign my copyright of this thesis toThe Charles Stark Draper

Laboratory, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts.

David W. King

Permission is hereby granted by The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. to the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology to reproduce any or all of this thesis.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF SYMBOLS ................................................ vi

INTRODUCTION.........................................................................1

1

GYROSCOPE DESCRIPTION AND SYSTEM MODEL................................5

1.1

Tuning Fork Gyroscopic Effect.............................................

5

1.2

Demonstration Model........................................................... 8

1.3

Micromechanical Configuration...........................

........... 13

2

D Y N A M IC S ...................................

............................................

2.1

System Model...............................................................

2.2

Neglected M odes....................................................................

2.3

Equations of M otion...............................................................

2.4

Simplified Output Solution.................................

..........

2.5

Simplified Output Transient Response......................................

2.6

Cross Axis Terms ....................................................

3

SYSTEM RESPONSE ANALYSIS................................

........... 33

3.1

Periodically Time-Varying System ............................................. 33

3.2

Stability in Terms of the Mathieu Equation.............................

. 36

3.3

Approximate Forced System Response by Harmonic Balance............. 44

3.4

Numerical Solution ...................................................

...... 51

3.5

Stability in Terms of Floquet Theory................................... 63

4

SYSTEM MATHEMATICAL MODEL................................

.......

4.1

Motor Model ................................................

4.2

Sensor M odel ........................................................................

4.3

Mechanical Factors ....................................

...............

4.4

Dam ping M odel.....................................................................

4.5

Error Sources...............................................

...................

5

D E SIG N .....................................................................................

5.1

Geometric Constraints .............................

5.2

Performance Tradeoffs ........................................

16

16

19

24

27

29

30

66

68

81

84

88

95

105

106

109

6

CONCLUSIONS ...........................................................................

Comparison with Current Micromechanical Gyro Configuration.........

6.1

Comparison with Previously Developed Tuning Fork Gyros................

6.2

6.3

Future Research ................................

116

118

120

122

REFERENCES ............................................................................. 125

APPENDIX ............................................................................

..

127

LIST OF SYMBOLS

ly

10

Io

kt

bt

Wx (Ch.2)

Wz (Ch.2)

ton

(0

19bi

ifb

I

Ix

Iz

Alz

Ix,y,-:Iz

6x'1 iy',11z

E

G

L (Lt, 1)

h

w

If , fy

fz (2b)

fx (2a)

mf

mw

mp

mt

principal mass moment of inertia about sensitive axis

nominal ( non-oscillating ) component of Iy

oscillating component of Iy

rotation angle of the fork relative to its base

linear stiffness coefficient of torsional spring

linear damping coefficient of torsional system

applied angular rate about sensitive axis

applied angular rate about x-axis

applied angular rate about z-axis

motor (tines) driving frequency

natural frequency of torsional system

system frequency when od is tuned to on

angular velocity vector of fork base with respect to inertial space

angular velocity vector of fork with respect to its base

angular velocity vector of fork with respect to inertial space

inertia tensor

principal mass moment of inertia about x-axis

principal mass moment of inertia about z-axis

oscillating component of Iz

unit vectors corresponding to fork axes

unit vectors corresponding to fork base axes

modulus of elasticity for silicon

torsional modulus of elasticity for silicon

length of tines (y-dim)

height of tines (z-dim)

width of tines (x-dim)

length of flexures

thickness of flexures

width of flexures

mass of each flexure

mass of each wing

mass of each inertial proof mass

mass of each tine

Wx, Wy, wz

Q

a,q

a (t)

b (t)

c (t)

d (t)

G (t)

B (t)

an

bn

x

F1

F2

F0

eO

d

g

Vd

V0

w (z)

K (k)

E (k)

sn (x)

rOm

rot

xl

x2

Ci

Cd

CO

AC

Cfb

Rfb

x,y,z dimensions of each wing, respectively

system quality factor

gyroscope mechanical gain

Mathieu Equation parameters

second derivative term coefficient to 2nd order LP equation

first derivative term coefficient to 2nd order LP equation

first order term coefficient to 2nd order LP equation

forcing function term for 2nd order LP equation

system plant matrix

system forcing matrix

Fourier sine coefficients

Fourier cosine coefficients

state transition matrix

second order system state vector

parallel electric flux motor force

fringing electric flux motor force

total motor force

permittivity constant

nominal distance between tines

nominal distance between wing and bridge electrode

differential driving voltage

voltage with respect to ground applied on each tine

conformal transformation function

complete elliptic integral of first kind

complete elliptic integral of second kind

Jacobi's elliptic sine function

nominal distance between inertial mass center and sensitive axis

nominal distance between tine center and sensitive axis

distance from sensitive axis to front edge of sensor plate

distance from sensitive axis to back edge of sensor plate

amount of sensor capacitance increase due to rotation

amount of sensor capacitance decrease due to rotation

nominal capacitance of each pair of sensor plates

net change in capacitance output signal

output amplifier feedback capacitance

output amplifier feedback resistance

vii

Ox

sensor excitation voltage

sensor excitation frequency

B

bandwidth of output signal filter

eout

output voltage

bx, by, bz

x,y,z dimensions of strain beam slot, respectively

boron-silicon misfit factor

4Isi

Poisson's ratio for silicon

a0

axial prestress on flexures

U00

maximum free stream air velocity normal to wings

viscosity of air flow over wings

Ex

QU

volumetric flow rate through sensor channel

Qf'

profile flow rate through sensor channel

Ff

damping force due to flow impingement

Fp

Az

damping force due to pumping effect

amplitude of tine vibration at tine midpoint

z-direction misalignment of proof masses

AB

amplitude of white Brownian Noise

Aa

amplitude of white amplifier noise

a (BW)

b

system bandwidth

Ke

electronics constant

Boltzmann's constant

xm

KB

K0

dynamics constant ( 10 o)

ass,B

capacitance constant

output standard deviation due to Brownian Noise

ass,a

output standard deviation due to amplifier noise

K1

sensor excitation constant

mx, my, mz

x,y,z dimensions of each proof mass, respectively

u2

ratio of tine vibration amplitude to its maximum limit

output oscillation amplitude in quadrature due to unbalance

0quad

viii

INTRODUCTION

During the past several years, rapid advancements have been made in the fields of

integrated circuits and microchip processing. The efficiency and accuracy in which silicon

can be etched into tiny structures with dimensions in microns has led scientists to pursue the

possibility of producing mechanical elements on the microchip level. Devices such as

accelerometers, pressure transducers, flow sensors, force transducers, electrostatic actuators,

and miniature microphones have already been developed and are beginning to become

commercially available. The advantages of micromechanical elements are obvious. The

small size of the devices open up areas of application previously deemed unrealistic. For

example, micromechanical sensors are sought after for various biomedical purposes in which

conventional sensors are ineffective due to size restrictions. Also, the semiconductor batch

processing techniques applied to mechanical structures greatly reduces the cost for mass

production. It has now become vital for sophisticated sensors to become available cheaper in

order to keep in pace with the rapidly decreasing cost of microprocessors. The two

fundamental properties of silicon make it an excellent material for sensing instruments. Its

semiconductor electrical properties allow easy integration with system electronics, and its

strong mechanical properties allow micromechanical instruments to be safely operated in high

impact or acceleration environments.

Following this trend, in 1983 the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. initiated the

design and development of a novel micromechanical gyroscope. This represented the first

development of its kind and led to a full scale project with the final goal being a complete

three axis micromechanical inertial guidance system. It has been forecast that the system will

be operated in a strapdown mode with on-chip electronics, and only consist of one square

inch flatpack. The gyroscope, designed by B. Boxenhorn [1,2] is planar, etched from a

silicon wafer, and uses an oscillating angular momentum vector to sense angular rate about

the axis normal to the gyro plane. A vibrating outer gimbal, supported by torsional pivots,

vibrates sinusoidally driven by electrostatic torquers. The oscillating angular momentum

vector, combined with the angular rate, produces a gyroscopic torque on an inner gimbal

causing it to vibrate about the other planar axis at the driving frequency. The inner gimbal

has a vertical bar mounted on it to add inertia to the gyroscopic element. The amplitude of the

inner gimbal vibration is proportional to the applied angular rate and is sensed by

ultrasensitive variable capacitance plates. The driving and sensing of the device is done by

fixing electrodes above the gimbals and applying appropriate voltages.

The gyroscope has been extensively modeled, built, and tested. On 1 September

1987, The first ever micromechanical gyroscope was shown to produce gyroscopic action.

Since that important milestone rapid improvements have been made on the device including

the design of a closed loop rebalance system, improvements in fabrication techniques making

possible a monolithic structure with buried electrodes, and analytical models of the noise

sources. The most recent test results, operated closed loop, show a gyro sensitivity of 3.13

mV/rad/sec with a noise level equivalent to 2500 degrees per hour. The gyro is projected to

achieve angular rate sensing accuracy within 10 degrees per hour upon completion of the

development program. At that point the device is expected to be useful in applications such

as small projectile guidance, kinetic energy weapon guidance and control, land vehicle

guidance and control, flight vehicle structure control and sensor stabilization, and robotics.

These applications exploit the micromechanical gyroscope's qualities not present in

conventional gyros such as small size, low cost, and ruggedness.

The idea of a vibratory gyroscope is not new. In the 1950's extensive research was

performed on vibratory angular rate sensors. The most popular configuration analyzed was

that of a tuning fork, where the two fork tines are forced to vibrate aganinst each other to give

an oscillating mass moment of inertia about the input axis. This, in turn, produces an

oscillating torque about the axis of the fork stem proportional to an applied angular about the

same axis. The Sperry Gyroscope Company designed and produced a class of these

instruments labeled the "Gyrotron Angular Rate Tachometer" [3]. Sperry envisioned that the

Gyrotron would become a high performance gyro suitable for long range navigation

applications. The Gyrotron, they believed, would acquire very high accuracy through

continued research on eliminating the zero rate error and further modification of the angular

displacement sensing technique. A decade of research continued, but, as seen retrospectively

thirty years later, the tuning fork gyro proved unsuccessful and its development was

terminated.

However, it has become desirable to investigate the potential of a tuning fork

configuration on a micromechanical level, and that is the basis of this thesis. Several factors

inspired the study of an alternate configuration micromechanical gyroscope, and they are

listed below:

1) An investigation of the feasibility of producing a micromechanical gyroscope with

an input axis on the same plane as the gyro. A combination of two of these gyros

with the current gyro would enable three gyros on a chip to sense angular rates about

all three axes.

2) A thorough analysis of the tuning fork dynamics. The previous analysis of

tuning fork gyros neglects the time variant terms that appear in the equations of

motion. On a micromechanical level these terms become significant since it is a

lightly damped system of high frequency. It is thus necessary to determine the effect

of these terms on the gyro response and if they lead to regions of instability and

poorly behaved output.

3) A simple but adequate design of a micromechanical tuning fork gyroscope. This

would make it possible to determine the performance characteristics of the gyro

including its response, mechanical properties, electrical properties, and noise

levels.

4) A comparison of the open loop performance capabilities between the current

configuration and a tuning fork.

5) A conclusion on whether a tuning fork gyro could be successful on a

micromechanical level even though all previous development efforts failed.

The thesis begins with a description of the gyroscopic properties of a tuning fork and

the micromechanical gyro model to be studied. The equations of motion for the instrument

are then determined rigorously by Hamilton's variational methods. This approach to the

dynamics has not been attempted in the literature and will give greater insight into the system

and the various small order terms neglected in the literature [3,4,5]. The next section of the

thesis analyzes the full equations of motion. Due to the time variant terms in the equations no

closed form solution is possible, and approximation methods are used. First, the

homogeneous equation is transformed into Mathieu's Equation which makes it possible to

approximate the system stability characteristics. The approximated stability region is then

checked by Floquet theory. An approximate infinite series harmonic solution is obtained for

the forced equation of motion to evaluate the various harmonic components as a function of

the system parameters. The approximate system responses are reinforced by a thorough

numerical simulation of the system. The last part of the paper gives design parameters of a

micromechanical tuning fork gyro and calculates a set of perfomance characteristics based on

a thorough mathematical model of the system. The design is done such that the device can be

built using microfabrication techniques, the response is open loop stable with maximized

sensitivity, and the identified noise levels are kept to a minimum. The thesis ends by drawing

conclusions on the feasibility of a micromechanical tuning fork gyroscope as an angular rate

sensor.

1

GYROSCOPE DESCRIPTION AND SYSTEM MODEL

1.1 Tuning Fork Gyroscopic Effect

The operating principles of the tuning fork gyroscope are straight forward. It is

possible to explain the gyroscopic torque of the device using Newton's laws, a freshman

physics background, and referring to the generic schematic of a tuning fork given in Figure

1.1. This description of the gyroscope is not adequate for analytical purposes, but it should

give the reader a clear understanding of the operating principles.

The two fork tines are forced to vibrate 180 degrees out of phase with each other at

the same frequency, od. The vibration causes the structure to have an oscillating mass

moment of inertia about the y-axis, which is the fork axis of symmetry and will hereafter be

labeled the sensitive axis. The principal inertia about this axis can then be written as the sum

of a constant term and an oscillating term,

*

Iy = I0 + Ilsin cot.

(1.1-1)

In addition to the forced tine vibration, assume that the tuning fork has only one degree of

freedom which is rotation about the torsional fork stem. The stem acts like a linear torsional

*

spring with stiffness kt. Further assume that the system is damped linearly, and let the

damping coefficient be labeled bt. The spring and damping act as restraining torques such

that

STy

= - kt - bt.

(1.1-2)

Let the base of the fork be fixed to a specific object which is being rotated with respect to an

inertial reference frame, such that the component of the rotation vector along the fork

sensitive axis is denoted by Q. From Newton's laws the sum of the torques about the

sensitive axis equals the time rate of change of the angular momentum component such that

ITy

-kt0 - bt

dt (Hy

*

=

d

dt[( I0 + Il1sin dt ) (0 + )]

(1.1-3)

Differentiating the right hand side and neglecting the 0 terms, the fork equation of motion

becomes

(1+

sin odt) O+(.L +l-+

cosodt ) 6 +n2

=

cos dt

(1.1-4)

where Con is the torsional natural frequency of the fork,

2

kt

n,

O

Y

Sensitive

SAxis

Forced

Vibration

k tines

fork heel

(rigid)

torsional

stem (weal

in torsion,

in bending

base

(fixed to

platform)

Figure 1.1

Tuning Fork Schematic

A rigorous derivation that includes an analysis of the neglected terms of Equation (1.1-4)

is the basis of Chapter 2. However, this simple derivation gives insight into the physics of

the tuning fork gyroscope. For instance, it is clear that the gyroscopic torque term,

comes from the oscillating angular momentum about the sensitive axis and is proportional to

the magnitude of the angular rate component about the sensitive axis. It is also evident that

the gyroscopic torque is oscillatory at the same frequency as the vibrating tines yet in

quadrature with it. It appears that an instrument can be designed that transforms the

oscillating gyroscopic torque into an output signal. This is accomplished by measuring the

magnitude of an oscillating angular displacement of a torsional spring. The measurement

signal can then demodulated to determine the applied rate direction, and filtered to eliminate

sensitivity to lower frequency torques.

Obviously, the tuning fork instrument has little resemblence to the conventional

rotated wheel gyroscope. Conventional gyroscopes are best characterized by an angular

momentum vector produced by a spinning member which tends to remain fixed in space.

Conventional gyroscopes detect angular rate about a particular axis by measuring the

displacement of the spinning axis relative to a gimbal axis. The magnitude of the

displacement is proportional to the applied rate about a sensitive axis. On the other hand, the

tuning fork instrument has an oscillating angular momentum vector, and yields an AC

signal, which has its magnitude at a specified driving frequency proportional to the applied

rate about a sensitive axis. Previous papers avoided the label gyroscope in describing the

tuning fork angular rate sensor. This was meant to keep the reader from thinking of the

tuning fork gyroscopic reaction as produced by some fixed angular momentum vector. In

this paper, however, the label gyroscope is used to describe the micromechanical tuning

fork instrument. The reason is simple. The famous French physicist Jean Bernard Foucalt

coined the term from its Latin translation to view rotation. The prefix gyro thus stems from

the sensed angular rate, and not the instrument's rotating member.

Throughout the years, many people have had difficulty obtaining a physical feel for

the action of a conventional gyroscope. With the exception of the spinning top toy, objects

with a spinning member are generally not free to be rotated. Therefore, the gyroscopic

reaction is not often observed in nature. However, there are several cases in nature where an

oscillating body is rotated. For one example, consider a child playing on a swing set. The

child, standing on the swing, is set in motion by a friend pushing him, which is the same as

an external torque applied to a rotational system. Slowly, but surely, the swing motion will

damp out and the child's ride will end. But, as discovered by many ten year old

experimentalists, if the child begins to squat up and down on the swing at the proper

frequency, the swing will remain in motion. The squatting produces a periodic variation in

the system mass moment of inertia, and hence causes an oscillating torque if it is in phase

with the swing oscillation. This torque is proportional to the swing's angular velocity which

is analogous to the tuning fork gyroscopic torque.

1.2 Demonstration Model

Even though it is likely that many people, at one time or another, have squatted up

and down to force a swing, the reader may remain unconvinced that a tuning fork can sense

angular rate. This leads to the first goal in the development of a micromechanical tuning fork

gyroscope: to physically demonstrate that a tuning fork can produce a measurable

displacement which is proportional to an applied angular rate. To show this, a large scale

model was designed to serve the function of a classroomdemonstrationmodel . It is

intended to give greater insight into the physical properties of the device.

The model is shown with dimensions in Figure 1.2. The structure may not look

much like a tuning fork, but it has the same basic characteristics. The model consists of a

structure closed at both ends containing only a single tine. A closed fork is preferred to an

open-ended structure to provide structural integrity and symmetry. For practical purposes a

single tine is not desirable since it produces an inertia function which is unsymmetric about

the sensitive axis. Unsymmetry leads to unbalance torques and cross-axis sensitivity.

However, the demonstration model is operated by simply exciting the tines at their

fundamental frequency. A double tine structure is not feasible since it would require an

identical tuning of both tines.

For the single tine the inertia function becomes

I

where

= (I + I)

2

Ii1= Imax - 10 , and

co

+ -L sin 2ot t

2

(1.1-5)

= driving frequency (tine fundamental frequency).

This differs from the double tine symmetric inertia function given in Eqn. (1.1-1) for two

tines. For the single tine, the gyroscopic torque will be vibratory at twice the driving

frequency and proportional to half of the oscillating inertia component.

The model was fabricated using beryllium copper sheets, aluminum, bronze, and

wood. The single copper tine is fixed at both ends by a sandwich joint between aluminum

blocks. Attached at the midpoint of the tine is a bronze block which acts as the high density

inertial proof mass. There are two torsional flexures at each end of the device, along the

sensitive axis, made from thin rectangular copper tabs which are sandwiched into the

aluminum wings and secured to the frame. The frame is attached such that the tension in the

tine, and the length of the flexures, can be easily altered. This flexibility is necessary to

accurately tune the device since for any appreciable gyroscopic torsional vibration the model

must be operated at resonance. This means that the torsional resonant frequency of the

flexures must be twice the fundamental frequency of the tine as seen from Eqn. (1.1-5).

The model was designed such that the tine and flexures were stiff enough to hold

sufficient energy to reduce damping, yet flexible enough to yield a visible frequency. The

flexure torsional stiffness was assumed to follow the equation,

G 3 16

Kt = r ab [3-

3 .3 6 ba+

b5 ]

0. 2 8 (-)

where,

G = torsional modulus of elasticity

L = flexure length

1

a = 7 flexure width

(1.1-6)

1

b = 2flexure thickness

which is given by Roark and Young [7]. The fundamental frequency of the tine was

determined by assuming a fixed-fixed beam, and using Dunkerley's equation [8] to

accomodate the effect of the inertial mass, so that,

2 =

112 t222

Ol l2

where,

)b = W

1 1 2+(02 2 2

+0)222

011 2 = 24.7mbL3)

and

(0222= 6(mL7)

(1.1-7)

o b = tine fundamental frequency

l 1 = fundamental frequency of beam by itself

(022= fundamental frequency of proof mass on a massless beam\

mb = mass of tine

mm = mass of proof mass

L

= tine length

Dunkerley's equation is a useful technique in analyzing structures that have known

stiffness properties, yet have significant masses attached to them. The equation gives a

lower bound for the beam frequency by solving the characteristic equation of the system

flexibility matrix, and neglecting the higher mode components.

For the model, the frequencies were calculated at con = 56.3 Hz and cob = 20.1 Hz.

Tuning the device such that on = 2cb was accomplished by applying tension to the tine to

push up the tine frequency while lengthening the flexures to decrease the torsional

frequency, as indicated in Figure 1.3.

ntr

ITI

V#8 Saw

h""Lv"

rulI**W& I

PQres

K~

5*4amCa

VI EW

TOP

-..

.

. ....

.

ID

"lilb•

1 0/

,•-4

t -

. pins

[

yS

CWS

t5t

rtPWh

'LEWItet To wolb

AV

ldit

SI bE VI EW

Figure 1.2 Demonstration Model

11

twj

5A

N

pae(

Flexure natural frequency vs

Tine natural frequency vs

flexure length

applied tensile force

I

22

L

slenth (m)

Figure 1.3

P teb kfae

Resonance Tuning of Demonstration Model

Several observations were made on the model by vibrating the tine and applying an

angular rate, and they are listed below:

1. The forced vibration excites a twisting mode of the tine about the sensitive

axis. This mode must be of a sufficiently higher frequency than the driving

frequency since it results in an error vibration of the sensing wings.

2. The manually excited tine vibration damps out in less than five seconds due

mostly to energy losses in the joint at the wing, and vibration wave

reflections back into the beam. This indicates that the device design should

have no joints and a stable node where the tines are fixed to the wing.

3. Any misalignment in the z-direction of the proof masses results in an

unbalance torque about the sensitive axis. This should be minimized, yet

does not provide an error since this torque is in quadrature with the

gyroscope torque as shown later.

4. The thin torsional flexures, with sufficient tension applied, are very stiff in

all degrees of freedom as desired.

5. The higher frequency torsional vibrations damp out slowly, mostly due to

viscous air flow.

6. Tuning the system was difficult to achieve and maintain. This indicates that

the tines should be driven off resonance if possible, and a feedback loop to

lock the driving frequency to the torsional resonance is desirable.

7. Gyroscopic action appeared to occur, but was difficult to verify due to tine

damping and unbalance vibrations.

1.3

Micromechanical Configuration

Although the model failed to accurately verify the gyroscopic action, it did indicate

that a gyroscopic torque can be produced. The model also provided a set of useful

guidelines in proceeding with a micromechanical design. The most obvious requirement is

that the device should have only two degrees of freedom: a forced lateral tine vibration and

rotation about the torsional flexures. A simple, yet practical configuration is a double tined

fork, closed at both ends, with the entire structure homogeneous and etched from a silicon

chip. Attached at the midpoint of the tines is a high density metal, which serves to increase

the oscillating inertia. The flexures are attached to the substrate at each end of the sensitive

axis, and the entire fork is suspended over a well which allows the torsional vibration. The

configuration is shown in Figure 1.5. The geometry of the configuration is simple enough

that it is safe to assume that it can be fabricated by current micromachining processes such

as photolithography, masking, doping, selective etching, and electroplating or metallization.

The tines will be driven electrostatically by applying a sinusiodal voltage between

them. The output signal will be produced by detecting the change in capacitance between the

two fork wings and electrodes either suspended above the fork , or buried in the substrate

beneath it. This technique has several advantages. By keeping the driving force within the

fork, coupling betweeen motor and sensor is eliminated by assuring that no motor force is

transfered across the sensor gap. This coupling might represent an error source in the

micromechanical gyroscope designed by Boxenhorn [1,2], and in the tuning fork gyroscope

designed by Sperry [3,6]. Also, the properties of the silicon allow voltages to be applied on

the tines without laying wires across the structure. This configuration also reduces damping

since there are no joints, and the only air damping results from the sensor plates on the

wings. Various other methods for producing a micromechanical motor have been studied in

the literature [9] but electrostatics has been the most successful. The test results of the

Boxenhom micromechanical gyroscope [1] demonstrate the validity of this method.

This configuration appears to offer the benefit of allowing a significant magnitude of

11

the ratio !, which is the proportional to the gyroscopic torque, while maintaining only two

degrees of freedom. The subsequent chapters will provide a thorough analysis, design, and

performance evaluation, based on this configuration.

VO + VI slnwt

substrate

rsional flexure

nsor wing

vibrating tine

high density mass

VO

+ V1

sinwt

SI

sensing electrodes

,7~7

/

/

substrate

//

/

/

7/

/

/

/

Figure 1.5 Micromechanical Configuration

i

/

2

DYNAMICS

2.1 System Model

The device is modeled as a dynamic system consisting of only one degree of freedom.

Figure 2.1 shows a simplified representation of the system. It contains a rigid oscillating

inertia, which represents the fork structure, attached to a torsional spring. The spring is

rigidly attached to a base. It might seem ambiguous that tine vibration is not considered a

degree of freedom, but since its motion is constrained by the motor and its dynamics are

neglected, the tine vibration is accounted in the fixed oscillating inertia term. The tine

dynamics are neglected by assuming that the driving frequency is significantly lower than the

tine fundamental frequency. Also, the motor is isolated sufficiently such that it exerts no

torques on the system. The only external torques acting on the system are the linear spring

torque, kt0, and a viscous air damping torque, btO. The geometry is assumed to be

symmetric such that any gravitational field will not result in any moment about the sensitive

axis.

Three separate coordinate axes are needed to describe the system and are shown in

Figure 2.1. The x-y-z coordinate system is fixed to the base of the fork which is assumed to

be strapped to a moving body. The x'-y'-z' axes are fixed to the fork. The y' axis

corresponds with the y axis, and is the sensitive axis. The x' axis runs through the center of

the fork tines, and is the axis of the lateral tine vibration. The fork-based x' axis is related to

the base-fixed x axis by the rotation angle, 0. The z and z' axis are defined by the right hand

rule such that the z axis is normal to the substrate plane and the z' axis is normal to the fork

plane. The third set of axes represents an inertial reference frame and is denoted by X-Y-Z.

Define the angular rotation of the fork base with respect to the inertial frame as the

vector

16

Abi

=

Wx ix + fl y + Wzi

z

.

(2.1-1)

The component about the y axis is denoted by 0 since it is the angular rate that the

gyroscope is designed to detect. The angular rotation vector of the fork with respect to the

fork base is,

afb = 0ly.

Then, the angular rotation of the fork with respect to the inertial frame, referenced by the x-y-

z coordinates is,

fi= fb + Wbi

=

Wx ix + (a + 0) iy + Wz iz.

(2.1-2)

The inertia of the fork is defined as a tensor referenced by the x'-y'-z' axes. These

axes are chosen because they represent the principal axes for a symmetric design. Then, the

inertia tensor can be written as

I =

Ix00

0 Iy(t) 0

[

0 I(t)J

(2.1-3)

The principal inertia components about the y' and z' axes must be written as a function of

time due to the lateral vibration,

Iy (t) = 10 + Ilsin Odt , and Iz (t) = Iz + AIz sinodt,

(2.1-4)

where Od designates the motor driving frequency. The fork axes and the fork base axes can

be simply related by the rotation angle 0,

ix = ix' cosO + iz'sinO

iy= iyl

i z = iz' cosO - ix' sine.

(2.1-5)

Substituting (2.1-5) into (2.1-2) gives the angular rotation vector in terms of the fork axes,

..i = (Wxcos0 - WzsinO) ix' + (Q + 0) iy, + (Wzcose + QsinO) iz (2.1-6)

This represents the angular rotation relative to the the fork principal axes that the device inertia

is subjected to.

17

y, y'

sensitive axis

oscillating inertia tensor

lateral

vibration axis

air damping torque

le

base

inertial reference frame

Figure 2.1 System Model

2.2 Neglected Modes

The single degree of freedom model of Figure 2.1 is valid only if the entire fork is

rigid and free from structural vibrations. However, as observed from the demonstration

model, the high frequency motor and structural unbalances excite other vibration modes.

Three modes that demand concern are tine twisting, flexure bending about the x'-axis, and

sensor wing bending about the sensitive axis.

The concept of rigidity is often loosely defined. In this study it will be assumed that

if the free vibration frequency for a specific structural mode is significantly higher than the

motor frequency, the mode will remain unperturbed. Significantly higher is generally meant

meant to mean more than a factoroffour larger so that the dynamic load factor [7] from the

motor is approximately unity.

It is now the intention to show that for preliminary micromechanical design

dimensions the three aforementioned modes can be neglected. The modes are analyzed

individually as follows:

Tine Twisting: The tine is modeled as a vertical beam fixed at both ends, constrained from

warping, and excited by an unbalance moment, T. The moment is applied about the tine

longitudinal axis which is parallel to the sensitive axis. Figure 2.2 shows the model, and the

torsional spring constant for the tine is given by Roark and Young [7] as

k

=

0.3 G h w 3

Lt

.

(2.2-1)

The geometric dimensions are given in the figure. The free vibration frequency is then ,

0ob2 =

•

19

where It is the inertia of a single tine and the attached proof mass about its longitudinal axis.

The preliminary design dimensions yield the approximation,

1

It = 1o.

The driving frequency is assumed to be set at the torsional resonance of the flexures which

can be determined from the stiffness Eqn. (1.1-6). Substituting, and comparing the twisting

frequency to four times the driving frequency,

0.9 G hw

Lt o

3

> 16 5.3 Ga b3

L10

Io

(2.2-2)

which is valid provided,

h w3

Lt

80 a b3

Lf(2.2-3)

A suitable design, where the tine twisting is negligable, is when w > 5 b.

Flexure Bending : Each flexure is modeled as a beam fixed at the substrate end and subject

to an excitation moment about the wing end. Assuming a Bernoulli - Euler model which

neglects shear deformation and rotational inertia [9], the free vibration equation is

4

Apdu(y, t) + EI

u(y,

y4

= 0

where

A = cross sectional area of the beam

I = beam inertia about its neutral axis

p

=

density of the beam material

u (y,t ) = deflection curve of the beam

20

(2.2-4)

A solution of the form u ( y, t) = u ( y ) ei

t

is assumed, and fixed end - free end

boundary conditions are applied. The lowest eigenvalue solution to the transcendental

vibration equation [9] is,

0o2 = 12.4 E If

f4 p Af

(2.2-5)

where the subscripted terms denot the beam inertia, length and cross sectional are of the

flexure. Make the approximation E 2G, substitute If = ~ (2a) (2b) 3 , and compare to four

times the driving frequency as given by (2.2-2) yields,

1

mfLf2

40.4

-.10

m-f2

(2.2-6)

This statement is generally satisfied since the mass of the flexures are an insignificant portion

of the structure mass.

Wing Bending:

Each sensor wing is assumed to be fixed down its centerline, along the

sensitive axis, at its attachment to the flexure. The angular rotation, or the tine vibration,

could excite a bending moment about the y-axis, as shown in Figure 2.2. Again, using a

Bernoulli - Euler beam model with fixed end - free end boundary conditions, the

fundamental frequency is given by Eqn. (2.2-5). To correspond with the notation used for

the flexure bending, let the wing dimensions be denoted by

Lw

=

distance from sensitive axis to end of wing

aw

=

one-half of wing width

bw

=

one-half of wing thickness

mw

=

mass of the wing.

Comparing the fundamental wing bending frequency to four times the driving frequency

results in,

21

2.1 aw bw 2

Lw 3 mw

40.4 a b3

Lf 10

To approximate, assume the dimensions are such that

mwL

=- Io and

3

Lw = 5Lf.

Then, the constraint becomes

aw b3 2 20 a b3

(2.2-8)

which thickness

isachievable forconsiderably

awing

greater than the flexure thickness(2.2-8)

which is achievable for a wing thickness considerably greater than the flexure thickness.

22

SZ

u(y,t)

O4

L

7

y

Flexure Bending

T

A

!

•

_Jl

-e

i

m, G

t

|

z

Tine Twisting

f%

"

~

v

,%rhA

u(xt)

z

Wing Bending

Figure 2.2 Neglected Modes

2.3

Equations of Motion

A simple, direct approach to the system dynamics was undertaken in chapter 1

resulting in the equation of motion given by Eqn. (1.1-4). In the process, several

approximations were made and the analysis was only one-dimensional. In order to account

for the cross-axis terms, Hamilton's variational approach to the system dynamics is

performed which gives a more rigorous, indirect derivation of the equations of motion.

Hamilton's method uses an energy technique to determine the equations that the

system variables, or state vector, must obey so that the system remains at equilibrium with

the external forces and constraints. Hamilton derived a variationalindicator which measures

the magnitude of deviation from equilibrium due to incremental changes in the state variables.

The variational indicator is represented as an integral over the trajectory time period for a sum

of system work increments due to the variable deviations. The equations of motion are

obtained by setting the variational indicator to zero for arbitrary admissable state variations.

Joseph-Louis Lagrange derived a general equation [10] for a system that obeys Hamilton's

principle, and which bears his name,

~~T

T

-av

a4 j

for j = 1...n

where,

j

(2.3-1)

n = the number of state variables, and

T = system kinetic coenergy

4j = generalized coordinate for each state variable

V = system potential energy

'j = sum of all nonservative forces in the 4j dimension.

The reader is referred to Crandall et al [10] for a complete description of Hamilton's

variational methods.

24

From the single degree of freedom system model illustrated in Figure 2.1, the only

generalized coordinate is 41 = 0. The only nonconservative force acting on the system is the

linear damping, so that Zl = btL.

The kinetic coenergy is due to the angular rotation of the

fork ,

T =

1

.fi

O IL fi.

(2.3-2)

It should be noted that the system kinetec coenergy is equal to the kinetic energy since the

system is defined in a Newtonian reference frame. Substituting for the inertia tensor Eqn.

(2.1-3) and the angular rotation vector of Eqn. (2.1-6) gives,

T = •

+,(xcos-Wsin)

I Y(t) (Q+ 2 +1 Iz (t) (Wcose+Wxsine)

x

2

The torsional spring restraining force is the only source of potential energy, so that,

V =

kt 0 2

2

For the system, Lagrange's Equation (2.3-1) takes the form,

d DT I_--aTu-+ aV

---

= •0

where,

dT= --lyI

9dt aeT

-

I)and,

(t +

= ly(t)

+ +l)

_T= -Ix Wxcos- Wzsin0Wzcos+Wxsin

and,

+ Izt •WFos+W xsin

Wxcos_-W sine)

(2.3-4)

Putting it all together, Lagrange's Equation becomes,

25

Iy(t) (6+0+ ly(t) (+0)

+Ix( WxcosO-Wzsin0X Wxsin0+Wzcose) -

Iz(t) (WzcosO+WsinOX w.cosO-wsino) +k19 +bto =0.

(2.3-5)

The trigonometric terms in (2.3-5) can be expanded in a Taylor series to transform the

equation of motion into algebraic form. To simplify the expansion it can be noted that the

rotation angle, 0, is very small. For example, the rotation angle is on the order of 10-5

radians for the Boxenhorn gyroscope [1,2], so that first order approximations will result in

negligable errors. Letting sine0

0, cos0 = 1, and sin 2 0 = 0, and also substituting (2.1-4)

for the oscillating inertia functions, the equation of motion becomes

(lo + isindit+)

IodcOSd+e)

1+

+ (wx-

I - Iz(t))0 +'kt +bte = WxWz(Ix - Iz(t))

(2.3-6)

This second order differential equation represents the complete description of the

tuning fork gyroscope subject to an angular rate vector. In the literature on tuning fork

gyroscopes, only Fearnside and Briggs [5] included the cross-axis and small order terms in

the dynamics analysis. However, the analysis done by Fearnside and Briggs differs from this

paper in a few respects. Fearnside and Briggs assume the damping is of large magnitude,

which is not the case on a micromechanical level. They are then able to neglect second order

terms of the ratio Il Od . This reduces the significance of the time-varying terms present for

a lightly damped system which is studied in chapter 3. They also use a direct approach to the

dynamics and simply drop all cross-axis terms after noting that they limit the device accuracy.

The first simplification made on Eqn. (2.3-6) is to neglect the angular acceleration

term, Q.

The driving frequency is assumed to be high enough such that the frequency of

the input rate is negligable in comparison. It is then possible to drop the 0 term from the

equation of motion. It must be noted that a limitation is placed on the system bandwidth, but

the limitation is insignificant for practical applications. The driving frequency for a

26

equation of motion. It must be noted that a limitation is placed on the system bandwidth, but

the limitation is insignificant for practical applications. The driving frequency for a

micromechanical device is assumed to be in the 1-5 kHz range, and applications in guidance

or control areas do not require bandwidths greater than 100 Hz. The input frequency is thus

negligable compared to the output frequency, and no significant error results from dropping

the f term. The equation of motion can now be written in a more convenient form,

(1o + I1 sin odt) 0 -{ bt + I1 Od COSOdt) 0 + kt0 = -I1Z Od COS odt

2 x- W•) 0] sin Codt

+(Ix- I~o WWz - (W2w

- ) 0 - III WxWz +(W

(2.3-7)

2.4 Simplified Output Solution

A closed form solution to Eqn.(2.3-7) is not apparent. The first step to understanding

the behavior of the system is to drop all terms that complicate the equation and can be

reasoned to have minimal effect on the solution. The cross-axis terms on the right hand side

of the equation will be dropped first. These terms comprise a torque about the sensitive axis

that is much smaller than the spring restraining torque, the damping torque, and the

gyroscopic torque. The following section will give a more thorough analysis of the crossaxis effects. The equation can now be transformed to a solvable form if I1is considered

much smaller than 10, and Ilw is much smaller than bt. The equation is then a second order,

constant coefficient, harmonically forced oscillator,

Io0 0 + b+k

= -I10

cd COS Od t.

Assume a solution of the form,

0 = A sin odt + B cos odt,

substituting gives,

27

(2.4-1)

A=

-I

0,2 bt

-Io(kt - lo a) + kt ( kt - lo w ) + w2 b2

and,

B = kt- Io o

.

(2.4-2)

The rotation angle can be maximized if the driving frequency is set at the torsional natural

frequency such that,

Md

o =

(2.4-3)

Hereafter in this paper, when the frequency is denoted by the symbol o without a subscript,

it denotes the driving frequency tuned to the torsional resonant frequency. The output is then

a pure sine curve, in phase with the motor vibration,

8 (t)

=

bt

sin ot .

(2.4-4)

The linear damping coefficient can be written in terms of the system quality factor, Q ,

where

bt =

I00

-p

. A more convenient expression for the simplified output solution is

0 (t) =

-IQQ

I0(

sin aot.

(2.4-5)

If all the assumptions for the simplified solution are valid, the output angle is

proportional to the ratio of the oscillating inertia component to the nominal inertia component,

the system quality factor, the magnitude of the applied rate, and inversely proportional to the

driving frequency. This gives a calibrated measure of the angular rate about the sensitive

axis. The output signal can also be demodulated with the driving oscillation as a reference

28

2.5 Simplified Output Transient Response

Eqn. (2.4-5) gives the steady state vibration of the harmonically forced, linear

system. However, the second order dynamics of the tuning fork will lead to an oscillating

transient period that must be investigated in terms of system bandwidth. Eqn. (2.4-1) can be

written in the following form,

**

-I

2

*

-

n e

-+ "+

Q +

COd

COS Od t .

--

n

0

(2.5-1)

Let II (t) = I1 sin Odt, then Eqn. (2.5-1) can be written,

0

2

*•

Q0 +

-i (t)

10

o

Since this equation is linear, Laplace transforming yields,

-

-

S

I1

0

s

- G (s) .

s2 + ýS +Cn2

Q

(2.5-2)

G(s) represents the system transfer function, but it can not identify the system bandwidth

since it relates the input signal which has unknown frequency to an output signal oscillating at

the driving frequency. In order to transform G(s) into a DC transfer function, Gm(s), the

output signal is frequency modulated at the driving frequency. This means,

0m (t) = 8 (t) e1

Om (s)

=

or, in the Laplace domain,

Od

(s +j COd)

Replace s by s + j wd to give the DC transfer function,

-I

s +

---

m

j Cd )

o

(s + j Od)2 + -(S

Q

29

=

+ j (0d)+5

Q

Gm (s) .

(2.5-3)

Expanding, rationalizing, and setting the driving frequency at the resonant frequency,

Gm (s)

s +j0)[s s+ 2jws+

+S2 + _.Q2

4(os + f2(S

4c 2s

+2•

1Q+

(2.5-4)

Assuming that the system bandwith is much lower than the driving frequency , the

components of the transfer function can be written,

(s

I{s +

Imag (Gm (s)) =

4oýs + Q)2

and ,

- Ii

Real.(Gm (s)) =

I

21s +2(Q

(2.5-5)

It is clear that the quadrature component is small compared to the in-phase component so that

the signal has negligable phase shift during the transient period, and the sytem bandwidth is

BW = - .

2Q

(2.5-6)

2.6 Cross Axis Terms

The right hand side of Eqn. (2.3-7) consists of the gyroscopic torque term plus four

terms due to the input rate about the axes orthogonal to the sensitive axis. These terms lead to

torques about the sensitive axis of unknown magnitude. But, if these torques can be shown

to either have negligable effect on the system, or cause an output deflection that has no

component that is in-phase with the motor at the driving frequency, no error signal will

result. This is because appropriate signal filtering and demodulation can eliminate all signals

from the sensor rotation except the vibrational component in phase with the motor within a

30

~

component that is in-phase with the motor at the driving frequency, no error signal will

result. This is because appropriate signal filtering and demodulation can eliminate all signals

from the sensor rotation except the vibrational component in phase with the motor within a

small frequency band about wd. However, any quadrature or off-frequency signal must not

exceed the designed output range of the gyroscope.

The cross axis terms are analyzed term by term:

1) (Ix - IOz)(WxWz) : This causes a DC output which can be filtered out. The bias that it

causes can be made as small as possible by designing the nominal inertias about the x and z

axes to correspond. It appears from Figure 1.5 that the symmetry can be easily obtained by

adjusting the x and y dimensions of the proof masses.

2) (Ix - Iz)(Wx 2 - Wz 2) 0:

For a symmetric design where Ix= I0z, this term can be

regarded as a small deviation in the spring constant. But, assuming a driving frequency in

the 2-4 kHz range, and a practical limit on the cross axis rates of around 20 Hz, then kt = 6 2

10 >> (Ix - I0z)(Wx 2 - Wz2 ). Hence, this term will have less than a 0.01% deviation on

the spring constant and will not alter the output significantly.

3) AlzWxWz sin or : AIz is the oscillation inertia about the z-axis, and is thus small and

on the order of Ii. Again, for a high frequency system, this term is tiny compared to the

gyroscopic torque for any significant Q. It is also in quadrature with the gyroscopic torque,

so even for very small values of 9, the majority of the error signal from this term will be

eliminated by demodulation.

4) Alz(Wx 2 - Wz2) 0 sin ox : This term can be viewed as a high frequency deviation in the

spring constant. Since Ilz is generally on the order of 1%of Ioz, the maximum deiviation in

the spring constant from this term is only about 0.0001%. And the frequency component of

31

the term does not lead to difficulties since, when combined with the sinusoidal output, it

results in a double frequency torque.

In general, the cross axis terms do not lead to a significant limit on the accuracy of

the device. As shown in the subsequent chapters, for a micromechanical device, Brownian

and electronics noise are the predominant error sources. Zero rate errors, such as cross-axis

coupling, tend to be insignificant by comparison.

32

3

SYSTEM RESPONSE ANALYSIS

In this chapter, the system response to the complete equation of motion will be

studied. For the tuning fork to operate efficiently as an angular rate sensor, the output angle

must be a linear function of the input rate. Eqn. (2.4-5) shows a linear relationship, but in its

derivation the periodic terms in the equation of motion were neglected. It is necessary to

verify that the periodic terms have a negligable effect on the system response. A brief

overview of linear periodic equations is presented, and then the tuning fork equation of

motion is analyzed by several different analytical and numerical tools.

3.1 Periodically Time - Varying System

If the cross axis terms are neglected and the system is driven at its torsional resonance

so that on = COd = 0o, the complete equation of motion (2.3-7) becomes,

\

1 sin)t

+

+

.Io

Io

(1 + esin ox 0 +

cos

+ 02 8

-

1

0 Cos ct

or,

Io

+e )cos 0x

+ 0 0 =-

Q )cos 0t .

where

e =

Q =

the mechanicalgain

sytem quality factor.

Generally, the mechanical gain is a small number, and the quality factor is defined in

Eqn. (2.4-5). Equation (3.1-1) is a linear, time varying, periodic differential equation (LP)

of second order. Equations of this form have arisen in many different fields of application,

33

and hence many different analytical methods to describe the behavior of such systems have

been studied. The problem is that there is no uniform approach, such as the Laplace

transform for linear, time-invariant, differential equations, to describe these systems. There

are also no known exact solutions, which makes it necessary to treat each equation

individually by the most appropriate approximate method.

The equation of motion (3.1-1) is of the form

a (t) x + b(t)x + c(t) x = d(t)

where a, b, and the forcing function d, are all periodic of period T = 2 x / co . The main

deficiency with the simplified solution of Chapter 2 is that even though a(t) = 1 since E is

small, the periodic component of b(t) cannot be accurately neglected since 1 / Q is on the

same order as E for a lightly damped micromechanical system. This type of equation, with

nearly constant a and c and periodic b , is a rare and unexplored form of an LP equation.

Intuitively, the response to Eqn. (3.1-1) will be approximately the steady state and transient

response of sections 2.4 and 2.5 for a small value of the product parameter, EQ. But when

EQ grows greater than unity, and the periodic component of b(t) begins to dominate, the

oscillating response will deviate from the simplified solution. This can be viewed as a

periodic perturbation in the damping, so that as EQ increases the output frequency should

remain constant, but the output magnitude, phase, and bandwidth will be affected.

The periodic variation in the damping is an effective energy pumping of the system.

This results in a substantial increase or decrease in the amplitude of the output oscillations. A

physical example ofenergy pumping from the circuit design field is presented by Richards

[11]. By periodically changing the capacitor plate distance in an LC circuit network, it is

possible to pump the voltage across the capacitor, which results in a periodic damping term.

When done at the proper frequency and phase, this increases the magnitude of the voltage

across the capacitor. This view leads to the conclusion that for specific values of the

parameter eQ the output magnitude will increase without bound, and the system will cease to

34

be globally stable. The product of the mechanical gain and the system quality factor, EQ, will

thus be referred to as the stabilityparameter.

The stability problem of periodic systems is unique because small variations in a

periodic coefficient can cause the system to lie in a region of instability, separated by regions

of stability. In the tuning fork case, this means that as eQ is increased past a certain limit the

response could go unstable, but a continued increase in the parameter could stabilize the

system. The stability problem of periodic systems has been studied in depth, with particular

emphasize by Maclachlan [12], Richards [11], and Porter [13].

An optimized design of the micromechanical tuning fork gyroscope will maximize the

parameter eQ, since it is a factor in the output magnitude as shown by (2.4-5). It is thus

imperative to determine the stability characteristics of this parameter. Several techniques to

determine the stability of periodic systems exist. They include transformation to the Mathieu

equation, Lyapunov stability theory, Floquet theory, and numerical simulation.

In the literature, much research has been done on homogeneous equations of the

form

K +[a- 2q2

(t)]x = 0 ,

where V (t) is a periodic function. This is known as Hill's equation and has its roots date

back to 1886. A special case of Hill's equation that has received particular attention in regard

to stability is the Mathieu equation, and is given by

x + [a - 2qcos2t]x = 0 .

(3.1-2)

Approximate periodic solutions to Eqn. (3.1-2) have been obtained as a function of the

parameters a, q. Since the stability regions for the parameters have been well documented

[11,12], a useful technique to determine the stability of a particular LP system is to transform

it to the Mathieu equation. Then the characteristics of the transformed equation, plus the

particular transformation, yield information about the original equation. The disadvantage of

this approach is that an appropriate transformation must be found, and information can be lost

in the transformation.

35

Another approach is based on Floquet theory. This is recently emerging as a useful

technique to give an exact yes or no answer to a particular system stability. However, this

approach is limited in that it requires the computation of a discrete transition matrix, and its

respective eigenvalues, for a given set of parameters. For the majority of LP systems, the

discrete transition matrix cannot be obtained in closed form. Numerical techniques must be

used and the stability conclusions are only obtained for specific values of the parameters.

Lyapunov stability theory, a more theoretical approach, uses mathematical functional

analysis to check if a suitable bound can be determined for the system response. It has been

used successfully for many particular periodic equations, but it requires the formulation of a

suitable Lyapunov function. There is no defined method to determine the Lyapunov

function, and extensive trial and error is often the method employed. Unfortunately, the

Lyapunov function is not easily obtained for the tuning fork equation.

The last possible technique, numerical simulation, has the problems of truncation and

round-off error, and is very sensitive to errors around the stability limits. Also, the high

frequency oscillations in an unstable region can grow slowly over many periods, so extensive

computation time is needed to reach conclusions. Simulation, though, can be used to

reinforce analytical results and verify the forced system response.

3.2 Stability in Terms of the Mathieu Equation

In order to transform Eqn. (3.1-1) into a form of the Mathieu equation of (3.1-2), it is first

written in a more convenient form. Dividing through by the a(t) term and noting the first

order expansion

1

= 1 - E sin ot + O (E2 )

1 + E sin ot

36

(3.2-1)

gives,

2 1 - esin oca

)0 +

cos ax) 1 - e sin

+

0 +

= -E

co(I - esinct) Cos ct.

Again, neglecting the second order terms in e, gives

O + o+ E coos ot - Qsin wt i

+

2(

- esinwt)O = -eocosxt.

If, for a lightly damped system, the parameter i is on the order of e, then the sine

component of the b(t) term is negligable compared to the cosine component. This gives

0 + (

+e)

cos

+

t

2 (1 - esinot)O =-0 e tocos a.

(3.2-2)

An appropriate change of variables must be found that eliminates the b(t) term from

the homogeneous form of Eqn. (3.2-2). An appropriate transformation [11] is

x = 0exp- -

b(') d)

x=Bnp(2 ",

(3.2-3)

which transforms the equation

into

0 + b(t) 0 + c(t) 0 = 0

x + [c(t)

1.

- .

(t)

-41 b2(t)]xx0=

0.

(3.2-4)

Substituting the values for a(t) and b(t) from Eqn. (3.2-2) yields the transformed equation,

S+

t2 1 4•-) -- F.sin (°t - 1 -

4 Q2

2

cos

2Q

-2t COS2•t

4

x

= 0.

(3.2-5)

The oscillating component of the second term of Eqn. (3.2-5) is approximated by the sine

component since Q >> 1 and e << 1. The transformed equation is then written

37

x)

+

e sin at x = 0.

4Q /

](3.2-6)

To put this in the form of Eqn. (3.1-2) a change is made in the independent variable. Let,

COt

F.

Eqn. (3.2-6) is then written,

S

2

+

4

2e cos 21 x(t) = 0.

-

d-

(3.2-7)

Equation (3.2-7) is in the form of the Mathieu equation with the parameters

1

a=4 - -2 and q = e.

Q

An approximate solution to the Mathieu equation was first introduced by E. L. Ince in

1932. Since then, many mathematicians have studied the equation, and very accurate

approximate series solutions exist. The reader is referred to Mclachlan [121 for a thorough

treatise of the Mathieu equation and its solutions. A simple explanation of the solution

technique, and its application to the transformed tuning fork gyroscope equation of motion, is

presented here.

Since the Mathieu equation is second order and linear, the general solution is

x(') = Ct xl (T)+ C2 x2 (T)

(3.2-8)

provided that the system Wronskian vanishes identically. For a differential equation of

period T, it has been proven by Floquet [11] that the system solution at any time t is related

to the solution at time r + T by a complex constant factor. This says,

x (t+ T) = a x(r).

(3.2-9)

The two independent particular solutions of (3.2-8) are then

xl (r+ T) = al xl (r)+ a2 x2 (T)

x2 (r+ T) = a3 xl(C) + a4 x2 (T).

38

(3.2-10)

where the a's represent arbitrary complex constants. Combining (3.2-10) with (3.2-8) and

(3.2-9) gives,

[(al -a) Cl + a2 C2 ] + [ a3 C1 + (a4 - )C2] = 0.

(3.2-11)

A nontrivial solution to this equation exists only if

a,-o

a3 I

a2

a4 - o

0.

(3.2-12)

The Wronskian of the Mathieu equation is defined as

W

=

Xl

X2

dxj

dr

dx2

dr

It was shown by Porter [13] that for two independent solutions to the Mathieu equation, xl

and x2,

dW

the derivative of the Wronskian, , is identically zero. Then,

dr

W () = W (0),

and W (r +T) = W (r).

It is seen from Eqn. (3.2-10) that

W (C+ T) = (al a4 - a2 a3) W (c).

Therefore,

al a4 - a2 a3 = 1.

Substituting this into the determinant equation (3.2-12), a relationship is obtained

between two of the arbitrary constants and the periodic scaling factor, a

0 2 - (al + a4)

+ 1 = 0.

A root locus for this equation can be drawn where the free parameter, or gain , is

K = al +a4.

39

(3.2-13)

When K = 2 and K = -2, the roots become a = -1, and a = 1, respectively. At this

point, when the roots a cross from within the complex plane unit circle to outside the unit

circle, the system becomes unstable. This is analogous to the stability criteria of a discrete

system with poles in the z-plane. The instability is seen by noting that if the magnitude of a

exceeds unity the system output of Eqn. (3.2-9) will increase each period. The analogy to

discrete systems is another interesting topic altogether, and it enables periodic systems to be

readily analyzed in discrete state space form. This is the basis to Floquet theory which is

studied in a forthcoming section.

From Eqn. (3.2-9) it is seen that for a = 1 the solution is periodic with period T,

and for a = -1 the solution is periodic with period 2T. The Mathieu equation has period n

, so the goal is to adjust the value of the parameters, a and q , until solutions that have period

x or 2x are found. The corresponding values of the parameters represent the stability

boundaries. It is noted from the Mathieu equation (3.1-2) that as q approaches zero the

system reduces to a free oscillator with solution,

x (t) = C3 sin mt + C4 cos mt ,

for m

2

= a.

Assume an infinite series solution, that is periodic in x or 2x, and reduces to the free

oscillator, in the form,

xl (t) = cos mt + q C11 (t). + q2 C12 (t) + ...

x2 (t) = sin mt + q C2 1 (t) + q2 C2 2 (t) + ...

(3.2-14)

Since there are two parameters, the technique is to fix q, and write a as a power series in q,

a = 1 + at q + a2q2

+

...

(3.2-15)

For both the even and odd solutions, substituting Eqns (3.2-14) and (3.2-15) into the

Mathieu equation [12] yields differential equations for the coefficients Cij. It is shown

[12,13] that the resulting differential equations can be solved for an infinite sequence of

discrete values for the parameter a. These values are known as characteristicnumbers and

the corresponding curves from Eqn.(3.2-15) are the characteristiccurves.

40

Mclachlan [12] calculates the characteristic curves to high accuracy for both the even

and odd solutions, and labels them an and bn , respectively. The curves are plotted in the a-q

plane, and the regions bounded by the curves are checked by substitution to determine if they

represent stable or unstable regions. This stability chart is called theStrutt diagram after the

mathematician who first introduced it. A reprint of Mclachlan's diagram is shown in Figure

3.1. In the figure, the shaded regions are the unstable areas, and the unshaded regions are

stable areas.

For the transformed equation of motion (3.2-7) the Mathieu parameters are

1

a= 4

and

q = e.

(3.2-16)

This point lies very near the b2 curve in the a-q plane shown in Figure 3.1. For this point to

lie in a stable region, the parameters are restricted to place the point below the b2 curve.

Mclachlan's expansion for the b2 curve is truncated to give

1

b2

a = 4 --2 q2 + O(q4 ).

Substituting from Eqn. (3.2-16)

1

b2": 4--

4-

1

2 + O(E4).

(3.2-17)

The stability boundary is then,

eQ =

1

(3.2-18)

For the point to lie in the stable region of Figure 3.1, it is seen that,

EQ < /2 .

(3.2-19)

The approximate stability boundaries for the transformed equation are quite accurate.

The remaining problem is to determine the relationship between the stability of the

transformed equation (3.2-7) and the original equation (3.1-1). First, the change in the

independent variable from t to 'T,

from Eqn. (3.2-7), does not affect the stability

characteristics. It is a scaling and shift on the time axis. Stability criteria involves the limit as

time approaches infinity, thus a scaled shift does not affect stability definitions. The

41

Figure 3.1

Stability Regions for the Parameters of the Mathieu Equation

42

dependent variable change is given by Eqn. (3.2-5). The variable of concern, 0, is equal to

the transformed variable, x, multiplied by a scaling function

0 (t) = x (t)k(t)

where,

1 1

k(t) = exp[-,o(t + esinot)] .

A matter of concern is that the scaling function does not contain one-to-one correspondence.

But, the function is bounded by

kub = exp

t

-

where the initial constant is

koexp

ko = exp ()

t

.

For a high frequency, the upper bound of the scaling function is a large number at time t =

0, then it quickly dies to zero. Therefore, at the upper bound, the scaling function magnifies

the transformed variable, x (t), for small values of time. As time increases the scaling

function drives x (t) to zero. If the variable x (t) is shown to be stable, then the

transformation cannot destabilize the response, so that 0 (t) is also stable. The restriction

given by Eqn. (3.2-19) is thus a sufficient, but not necessary, condition for stability of the

equation of motion.

43

3.3

Approximate Forced System Response by Harmonic Balance