PHYSICIAN Teaching The Weight Loss

advertisement

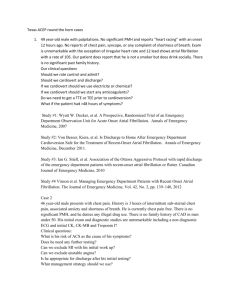

Teaching PHYSICIAN The January 2011 Volume 10, Issue 1 For those who teach students and residents in family medicine n Teaching Points—A 2-minute Mini-lecture Weight Loss By John Brill, MD, MPH, University of Wisconsin Editor’s Note: The process of the 2-minute mini-lecture is to get a commitment, probe for supporting evidence, reinforce what was right, correct any mistakes, and teach general rules. In this scenario, Dr Brill (Dr B) works with a third-year student (MS3). M3: Dr B, this is a 69-year-old Vietnamese man who came in for a cough. I thought it was just going to be a cold, but his wife noted that he has lost 20 pounds during the last 4 months without trying. I’m worried that he might have lung cancer. n Dr B: Lung cancer! Why are you thinking that? M3: I didn’t really know where to start, so I started—anatomically—with the digestive system. He denied any trouble with his teeth, swallowing, abdominal pain, bloating, jaundice, diarrhea, or change in stools. Dr B: Good. Then what did you do after that came up negative? MS 3: I thought about the times in my life when I lost weight and how those might apply to him. Dr B: Using your life experiences to relate to a patient? Good. MS 3: Just seemed like common sense. So, during college I used to lose weight when I was really stressed out. And when I had mono, I lost 15 pounds. My junior year I was totally broke and had to live on ramen noodles for a month. continued on page 2 Information Technology and Teaching in the Office Working With Learners to Better Educate Our Patients and Their Families By Thomas Agresta, MD, MBI, University of Connecticut Patient education and self-empowerment are some of the most important tasks we take on as family physicians. January 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 1 Clinical Guidelines..........................3 POEMs for the Teaching Physician........................................6 FPIN HelpDesk Answers................7 We know, and often teach our learners, that ultimately the patient and his/her family determine adherence to treatment plans, monitoring of symptoms, and taking on the challenging behavior changes required for prevention and treatment. Yet all too often, we shortchange the important task of helping them truly understand the implications of their disease, how to properly use their medicines, what to expect in that upcoming test or procedure, or when to call us for changes in symptoms or status. This is not purposeful but often occurs nonetheless simply because we do not have the time or knowledge of how to use available resources to most effectively facilitate this process. It is often quoted that patients remember only 20% of what we tell them (and not necessarily the 20% we think they should remember). This is true of complex communication that occurs in any setting. One helpful and effective strategy is to empower your learners to directly demonstrate how to access and use trusted on-line patient educacontinued on page 5 Teaching PHYSICIAN The Weight Loss continued from page 1 Dr B: So you used those experiences to ask him about . . . MS 3: Depression or anxiety: negative. Symptoms of infections: except for the cough, nothing. Access to food seems OK; his daughter cooks for him, and there’s plenty. He doesn’t drink alcohol or use drugs. I also thought about when I re-started running, and I lost 10 pounds, but he hasn’t changed his activity. Dr B: Excellent. How did you ask about depression? MS 3: I read that, to diagnose depression, you need at least one of the two main criteria of feeling sad or not doing things you usually enjoy, so I asked him about those two things. Dr B: One widely used screening test for depression, the PHQ-2, asks about those two things. Since the test is 95% sensitive, a negative result can help rule out depression. You mentioned weight loss when you had mono; think he might have that? MS 3: Mono is pretty unlikely in a 69 year old, but infections like hepatitis or TB could cause weight loss. Hep B and TB are more common in Southeast Asians, but he has tested negative for both in the recent past. sis Factor, that inhibit appetite. Where might he have a cancer? Dr B: In addition to thinking anatomically or remembering personal experience, you might also think mechanistically. When someone is low on something, be it pounds or potassium, it means there’s not enough coming in or being made; too much going out or being used up; or it’s going to the wrong place. Our patient seems to be getting enough calories in, not losing a lot of calories externally, not doing more activity, so we’re getting down to . . . MS 3: The only complaint that he has is the cough, and he used to be a big smoker, so he could have a lung cancer. MS 3: Something is making him burn more calories. That’s why I thought of cancer. Dr B: How does cancer make someone lose weight? MS 3: I’m not sure, but I have this picture of an evil cancer growing inside of him, and stealing all his calories, like a thief. Dr B: Quite an imagination you have. Well, you are partly right. Malignant neoplasms tend to be more metabolically active than other tissues. That’s really the basis for chemo and radiation therapy: cells that are replicating faster will be destroyed first. In addition, many cancers also produce hormones, such as Tumor Necro- Dr B: Very possible; lung cancer is the fourth most common cancer in US males, after skin, prostate, and colon. And, because of its higher mortality, it’s the leading cause of cancer death. Let’s summarize what we learned here today. MS 3: (1) Two ways to think about undifferentiated complaints like cough are anatomically and mechanistically. (2) An effective way to screen for depression in primary care is with a two-question screen asking about depressed mood or anhedonia. (3) A good history can usually take you to a correct diagnosis. (4) Cancers can cause weight loss through hormonal appetite suppression or increased metabolism. (5) Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Dr B: Superb! Now let’s go see him and talk with him about next steps. Alec Chessman, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Editor Helping You Teach Better—The STFM Resource Library Teaching Chronic Disease Management............................................................................... www.fmdrl.org/2853 Lifestyle changes are needed for patients to manage chronic disease. This presentation will help you learn to evaluate residents’ ability to be successful at motivational interviewing and eliciting behavior change in patients while precepting. Improving the Pelvic Exam: Reducing Iatrogenic Effects, Decreasing Distress, and Enhancing the Doctor-Patient Relationship.......................................................... www.fmdrl.org/3017 This presentation reviews the potential iatrogenic effects of speculum exams and techniques to improve the exams, reduce iatrogenic effects, and improve the doctor-patient relationship. Using the Practice Huddle to Teach Systems-based Practice and Teamwork......................... www.fmdrl.org/2890 The UC-Davis FPR Clinic implemented a Practice Huddle as part of becoming a PCMH. This presentation describes the rationale, steps, challenges, and outcomes of using a Huddle to teach systems-based practice and teamwork. 2 January 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 1 n Clinical Guidelines That Can Improve Your Care University of Michigan Health System: Acute Low Back Pain By Diana L. Heiman, MD, University of Connecticut With the snowy weather that just hit the entire mid-section of the country, there’s no doubt that many patients will present with acute low back pain (LBP). Even with my sports medicine training, it’s still the bane of my existence; I’m sure you are no different. The University of Michigan has an excellent set of evidence-based guidelines and this one on Acute Low Back Pain was revised at the beginning of 2010. (All of the University of Michigan guidelines are available for free at http://cme.med.umich.edu/iCME/ default.asp, and there is associated free CME available as well.) Although this guideline did not evaluate cost effectiveness, the recommendations can aid in performing an appropriate history and physical as well as further testing only as warranted by those findings. Patient education hand-outs are also available on the University of Michigan Web site at www.med.umich.edu/1libr/ guides/lowback.htm. Acute LBP is defined for guideline purposes as being of <6 weeks duration and occurring in patients over the age of 18. Subacute LBP falls in the 6 weeks to <3 months period, and chronic back pain is >3 months duration. Finally, recurrent LBP occurs in a patient who has had previous episodes of LBP in a similar location who is asymptomatic between episodes; 60%–80% of patients will experience recurrence within 2 years of initial episode of LBP. The guideline primarily addresses acute LBP but also addresses risk factors for developing chronic LBP and things to look for to identify malingering (Waddel’s five signs). Two of the more helpful tables are reproduced below: Table 1 breaks down the “red flags” into likely etiologies, and Table 2 lists the risk factors for chronic disability. These are probably the two areas we worry about most in evaluating patients and should be the focus of the initial visit. If risk factors for chronic disability are identified, aggressive management to prevent disability should be undertaken. Also important is realizing the fact that 90+% of patients with nonradiating LBP will have complete symptom resolution within 6 weeks, whereas 50% of patients with associated radicular symptoms will have resolution within the same time period. The remaining 50% will generally have continued improvement to resolution of pain, but the small percent with disabling pain remaining at 3 months have <50% chance of full recovery, and 10% of those remaining out of work at 1 year have <10% chance of returning to full work capacity ever without treatment. In general, at the first visit (regardless of whether pain is localized or radicular—pain below the knee) the evaluation includes a focused history and examination paying particular attention to the “red flags” in Table 1, risk for chronic disability in Table 2, and strength and reflexes on physical examination. If no red flags are present, all diagnostic testing is deferred unless the pain has been present for at least 3–6 weeks. Initial treatment involves: heat, stretching, analgesics, and muscle relaxants. Acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and COX-2 inhibitors can be beneficial in reducing pain and are appropriate to use and should be dosed around the clock (not prn) unless the pain is very minor. Muscle relaxants can also be beneficial, but have no proved additive effect when used with NSAID’s. Opiate pain medications are not indicated for non-radicular LBP and should be only used with extreme caution in radicular Teaching PHYSICIAN The The Teaching Physician is published by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, 11400 Tomahawk Creek Parkway, Suite 540, Leawood, KS 66211 800-274-7928, ext. 5420 Fax: 913-906-6096 tnolte@stfm.org STFM Web site: www.stfm.org Managing Publisher: Traci S. Nolte, tnolte@stfm.org Editorial Assistant: Jan Cartwright, fmjournal@stfm.org Subscriptions Coordinator: Jean Schuler, jschuler@stfm.org The Teaching Physician is published electronically on a quarterly basis (July, October, January, and April). To submit articles, ideas, or comments regarding The Teaching Physician, contact the appropriate editor. Clinical Guidelines That Can Improve Your Care Caryl Heaton, DO, editor heaton@umdnj.edu Diana Heiman, MD, coeditor dheiman@stfranciscare.org Family Physicians Inquiries Network (FPIN) HelpDesk Jon Neher, MD, editor ebpeditor@fpin.org Information Technology and Teaching in the Office Richard Usatine, MD, editor usatine@uthscsa.edu Thomas Agresta, MD, coeditor Agresta@nso1.uchc.edu POEMs for the Teaching Family Physician Mark Ebell, MD, MS, editor ebell@msu.edu Teaching Points—A 2-minute Minilecture Alec Chessman, MD, editor chessmaw@musc.edu continued on page 4 January 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 1 3 Teaching PHYSICIAN The Acute Low Back Pain continued from page 3 LBP. Their early use is associated with increased disability, even when controlling for severity. Activity should be prescribed as tolerated. Bed rest is bad! Especially for non-radicular LBP. Minor work restrictions and avoiding long spans of driving may need to be prescribed depending on the level of physicality of the job, but in general, activity is good as long as it doesn’t exacerbate the pain. Follow-up visits should occur weekly, unless the patient is initially kept out of work, in which case they should be seen in 2–3 days to reassess need to remain out of work. At each follow-up visit, improvement or deterioration in symptoms should be assessed as well as progression or regression of physical exam findings, specifically strength and reflexes. If pain is not improved at 1–2 weeks, formal physical therapy should be considered including manual therapy (manipulation) for non-radicular pain and McKenzie (extension) exercises for radicular pain. If radicular pain persists at 3 weeks, MRI can be considered. X-rays are not likely to show much. If the MRI is not diagnostic, an EMG can then be done to show the area of nerve root impingement. For patients at risk for chronic disability at any point, early referral to a multi-disciplinary back pain program, if available in your area, can be helpful in decreasing the likelihood of chronic disability. Also, referral to a back pain Table 1 “Red Flags” for Serious Disease Cauda Equina specialist can help in cases where pathology cannot be demonstrated objectively on MRI/EMG. Hopefully, this will help in managing the very challenging patients that undoubtedly will walk though your door in the near future. Reference Material University of Michigan Health System. Acute low back pain. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Health System, 2010 Jan. 14 p. [11 references] Available online at www.med.umich.edu/1info/ fhp/practiceguides/back/back.pdf. Caryl Heaton, DO, UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School, Editor Diana Heiman, MD, University of Connecticut, Coeditor Table 2 Risks for Chronic Disability Clinical Factors Fracture Cancer Infection • Previous episodes of back pain Progressive neurologic deficit X Recent bowel or bladder dysfunction X • Multiple previous musculoskeletal complaints Saddle anesthesia X • Psychiatric history Traumatic injury/onset, cumulative trauma X Steroid use history X Women age >50 X Pain Experience Men age >50 Male with diffuse osteoporosis or compression fracture Cancer history • Alcohol, drugs, cigarettes X X X • Rate pain as severe X • Maladaptive pain beliefs (eg, pain will not get better, invasive treatment is required) X • Legal issues or compensation Premorbid Factors X Diabetes Mellitus • Rate job as physically demanding X • Believe they will not be working in 6 months Insidious onset X X No relief at bedtime or worsens when supine X X • Don’t get along with supervisors or coworkers Constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, weight loss) X X • Near to retirement • Family history of depression History UTI/other infection X • Enabling spouse IV drug use X HIV X • Are unmarried or have been married multiple times Immune suppression X • Low socioeconomic status Previous surgery X • Troubled childhood (abuse, parental death, alcohol, difficult divorce) 4 January 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 1 Teaching PHYSICIAN The Working With Learners continued from page 1 tion resources to patients and family members. Giving them this important task can have many direct benefits for them as learners, as well as improving the quality, effectiveness, and overall satisfaction of your patient care. Many recent studies show that while patients increasingly use Internet resources for health information, they still believe that their primary care physicians are the most reliable and trusted source of information. Yet patients are increasingly asking their doctors to guide them in accessing quality online information.1 So how can you make it easy to have learners take on this task while in your office? • Have a predefined handout for patients that lists your trusted patient education sites. • Have the URLs for favorite patient education sites bookmarked on office computers and within your EMR system to enable quick and easy access during a patient encounter. • Post your preferred Patient Education Sites on your own Web site or patient portal. • Show the learner (student or resident) by example how you would like them to use the tool and watch them introduce a few patients or families to Web sites for the first time • Have them become familiar with sites as part of a homework assignment in between patient sessions, then ask them to teach you more about what is available. • Try and incorporate the demonstration of patient education sites into the “wait time” patients experience (waiting for a flu shot, an EKG, or bloodwork) • Give them guidelines and feedback about how much time to spend on a topic; often it is only necessary to show a patient where a resource is, talk about what it has within it, and then give them the URL for viewing on their own. • Have learners be responsible for creating a “Patient Education Prescription” as part of the health care plan and put that within their write up of the encounter. Having learners take on a substantive role in patient education while they rotate through your office will help them better understand the potential resources, see more clearly the common barriers that patients and their families face in adhering to our recommendations, and greatly increase the value that patients themselves place on learning more about their own health conditions. It can also be a means by which we help transition and empower our staff to take a greater role in this important task as we try to move our practices closer to Patient-centered Medical Homes. I would encourage you to give this a try—it has greatly enhanced my own teaching experience and has been highly valued by students empowered to take on this fun and exciting role. Reference 1. Iverson S, Howard BA, Penny B. Impact of Internet use on health-related behaviors and the patient-physician relationship: a surveybased study and review. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2008;108:699-711. Richard Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Editor Thomas Agresta, MD, University of Connecticut, Coeditor Examples of Trusted Patient Education Sites Web Site URL Comments Medline Plus http://medlineplus.gov/ Multi-media Web site maintained by National Library of Medicine—most sites Family Doctor.Org http://familydoctor.org/ Maintained by American Academy of Family Physicians KidHealth http://kidshealth.org/ Maintained by Nemours—sections for parents, teens, and kids. Interactive games and homework helper included. January 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 1 5 Teaching PHYSICIAN The n POEMs for the Teaching Physician ARBs and ACE Inhibitors Prevent AFib Clinical Question: Can angiotensin receptor blockers or angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors prevent atrial fibrillation in susceptible people? Study Design: Meta-analysis (randomized controlled trials) Funding: Self-funded or unfunded Setting: Various (meta-analysis) Synopsis: First, some plausibility: The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system seems to be involved in structural—and electrical—remodeling of the atrium; blocking this effect might prevent atrial fibrillation. We’re beyond theory, though, and these authors searched three databases, including the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, to identify 26 randomized controlled trials evaluating the effect of ARBs or ACEIs on the prevention of atrial fibrillation. All trials compared one drug with placebo or with conventional treatment for at least 6 months. Eleven of the studies enrolled patients without atrial fibrillation, 12 enrolled patients with atrial fibrillation, and three enrolled patients with or without atrial fibrillation. In other words, the authors of this meta-analysis combined all studies, regardless of baseline risk. Most of the studies were not specifically designed to evaluate the effect on atrial fibrillation, and only some of the studies (n=12) specifically tested for atrial fibrillation, and these only tested symptomatic patients. The quality of the studies was not formally assessed. There was no evidence of publication bias. Overall, the use of an ARB or ACEI significantly lowered the risk of atrial fibrillation. The study results were heterogeneous and analysis of specific subgroups of patients showed prevention was more pronounced in patients with recurrent as compared with new-onset atrial fibrillation and was greatest in patients also treated with amiodarone (odds ratio = 0.35; 95% CI, 0.25–.048). The effect of prevention in patients with heart failure was not clear. Bottom Line: Treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) or angiotensin-converting enzyme in- hibitor (ACEI) decreases patients’ risk of developing atrial fibrillation, especially patients with recurrent atrial fibrillation and those who are receiving treatment with amiodarone (Cordarone) to prevent fibrillation. The clinical application of this information is unclear, though it makes sense to use one of these classes of drugs in patients with recurrent atrial fibrillation who also have another indication for its use. (LOE = 1a-) Source article: Zhang Y, Zhang P, Mu Y, et al. The role of renin-angiotensin system blockade therapy in the prevention of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010;88(4):521-31. LOE—level of evidence. This is on a scale of 1a (best) to 5 (worst). 1b for an article about treatmen is a well-designed randomized controlled trial with a narrow confidence interval. Mark Ebell, MD, MS, Michigan State University, Editor POEMS are provided by InfoPOEMs Inc (www.infopoems.com) Copyright 2011 Shop Hassle Free With STFM When you shop online using the STFM Online Bookstore/amazon portal at www. stfm.org/bookstore, you can find everything you need: books, electronics, music, DVDs, clothes, housewares, and much more. You will benefit from the advanced technology that amazon.com uses to expedite and track shipments and recommend related books and other items. When purchases are made through STFM’s Bookstore/amazon portal, www.stfm.org/bookstore, STFM receives a small percentage of the total purchases (anything that amazon.com sells). www.stfm.org/bookstore 6 January 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 1 Teaching PHYSICIAN The From the “Evidence-Based Practice” HelpDesk Answers Published by Family Physicians Inquiries Network (FPIN) n What Is the Best Treatment for Chlamydia in Pregnancy? By Umera Ghouse, MBBS, and Anne M. Proulx, Wright State University FMR, Dayton, OH Evidence-based Answer For treatment of chlamydia in pregnancy, azithromycin 1 g taken orally as a single dose has similar effectiveness, better patient adherence, and fewer adverse effects than a 7-day course of either amoxicillin or erythromycin. (SOR A, based on a meta-analysis.) Amoxicillin and erythromycin, however, are less expensive. A 2007 meta-analysis pooled eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted from 1991 to 2006 with 587 patients to determine which treatment strategy for chlamydia in pregnancy was best. All patients had microbiologically confirmed Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Two RCTs compared azithromycin with amoxicillin, whereas six RCTs compared azithromycin with erythromycin. No difference was noted in treatment success of azithromycin compared with amoxicillin and erythromycin (six RCTs with 374 subjects; odds ratio [OR] 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82–2.57). Patients taking azithromycin reported fewer gastrointestinal (GI) side effects than patients taking amoxicillin and erythromycin (seven RCTs with 412 patients; OR 0.16; 95% CI, 0.06–0.4). Total adverse events were also fewer with azithromycin than with both comparators (six RCTs with 325 subjects; OR 0.13; 95% CI, 0.08–0.21). Patients treated with azithromycin also showed better adherence (seven RCTs with 413 patients; OR 21.96; 95% CI, 9.05–53.3).1 Limitations of this meta-analysis include differences in gestational age at time of screening and differences in timing of posttreatment cervical cultures for test of cure. Reinfection rates may be decreased with more advanced gestational age because of decreased sexual intercourse rates. Later gestational age at detection may also reduce pregnancy-related GI symptoms and affect perception of medication side effects. Another limitation is the grouping of GI side effects and total adverse effects of amoxicillin with erythromycin, instead of evaluating each separately.1 The 2006 updated Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for the treatment of chlamydia in preg- nancy advocates the use of azithromycin 1 g in a single dose or amoxicillin 500 mg three times a day for 1 week.2 Treatment costs differ significantly: Azithromycin was priced at $29 versus amoxicillin for $14 and erythromycin for $17 from a major online pharmacy (http:// www.drugstore.com, accessed September 16, 2009). References 1. Pitsouni E, Iavazzo C, Athanasiou S, Falagas ME. Single-dose azithromycin versus erythromycin or amoxicillin for Chlamydia trachomatis infection during pregnancy: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007;30(3):213–21. [LOE 1a] 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM. Diseases characterized by urethritis and cervicitis. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2006 [published errata appear in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55(36):997]. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-11):35-49. http:// www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5511.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2009. [LOE 5] SOR—strength of recommendation LOE—level of evidence Jon O. Neher, MD, University of Washington, Editor HelpDesk Answers are provided by Evidence-based Practice, a monthly publication of the Family Practice Inquiries Network (www.fpin.org). STFM Annual Spring Conference Register now at www.stfm.org/annual April 27–May 1, 2011, New Orleans The Annual Spring Conference offers presentations focusing on best practices, new teaching technologies, emerging research, and public policy issues. 7 January 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 1 Know someone outstanding? Nominate him or her for the 2011 Pfizer Teacher Development Awards, honoring outstanding community-based family physicians who are part-time teachers of family medicine. Each recipient receives $2,000 in scholarship funds, $500 stipend for a recognition event, and a framed certificate. Eligibility requirements: • Member of the American Academy of Family Physicians • Recent graduate of an ACGME-approved family medicine residency program (2004-2010) • Community-based family physician who also teaches as a preceptor or as an educator of family medicine residents and students • Practices in community settings or clinics (not in educational institutions or practices funded or sponsored by an educational institution) • Teaches on average no less than four and no more than 32 hours per month • Teaches voluntarily or receives no more than $18,000 annually for educational time To nominate yourself or someone else, go to www.aafpfoundation.org/ptda and download an application packet. Submit your completed application by April 29, 2011. Questions? Contact (800) 274-2237, Ext. 4457, or sgoodman@aafp.org. Support made possible by the AAFP Foundation through a grant from Pfizer Inc. January 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 1 8