Proper Name Retrieval 1

advertisement

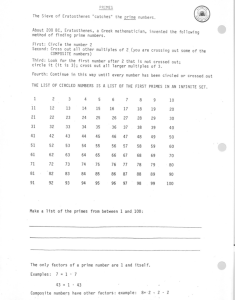

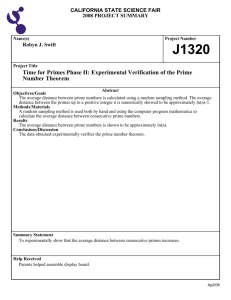

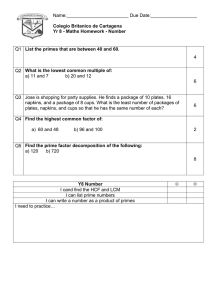

Proper Name Retrieval Running head: PROPER NAME RETRIEVAL Semantic Category Moderates Phonological Priming of Proper Name Retrieval During Tip-ofthe-Tongue States Katherine K. White1, Lise Abrams2, and Elizabeth A. Frame1 1Rhodes 2University College of Florida Author Note: We thank Greg Palm, Rachel Stowe, and Keshav Kukreja for assistance with stimuli development and data collection, and Meagan Farrell for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Portions of this research were presented at the 23rd annual convention of the American Psychological Society, Washington, DC, and the 52nd annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society in Seattle, WA. Correspondence concerning this article should be sent to Katherine White, Department of Psychology, Rhodes College, 2000 N. Parkway, Memphis, TN 38112. E-mail: whitek@rhodes.edu. 1 Proper Name Retrieval 2 Abstract Despite evidence that the majority of tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) states occur for proper names, little research has investigated factors that influence their resolution. Although phonological primes typically increase TOT resolution, the present experiment investigated whether priming effects are mitigated by semantic competition. Participants read questions whose answers were proper name targets (e.g., Helen Hunt, Elton John) from various semantic categories (e.g., actor, musician). Following a TOT, another question was presented that either included a prime name that varied in phonological overlap with the target (full first name or first syllable) and semantic category (same profession, different profession), or was phonologically and semantically unrelated to the target. After presenting the target question a second time, participants were more likely to resolve TOTs following first-name primes than unrelated names, independent of semantic category. In contrast, first-syllable primes marginally facilitated TOT resolution when the prime was in a different semantic category but not when the prime was in the same semantic category. These results demonstrate that semantic overlap increases competition from phonologically-related names when there is incomplete phonological input, allowing an alternative name to prevent TOT resolution. Keywords: tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) states, proper names, phonological priming, semantic competition Proper Name Retrieval 3 Semantic Category Moderates Phonological Priming of Proper Name Retrieval During Tip-of-the-Tongue States Almost everyone has experienced a time when a famous name evaded retrieval: When attempting to recall the singer of Candle in the Wind, the name Elton John may be temporarily unavailable for retrieval. Oftentimes this frustrating memory lapse, known as a tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) state (e.g., Brown & McNeil, 1966), is accompanied by a persistent and salient name that one knows is not correct (e.g., Elvis Presley). These alternate names frequently share various characteristics with the intended "target" name, including phonological features such as first letter and number of syllables, and syntactic features such as part of speech (e.g., Brown & McNeill, 1966; Burke, MacKay, Worthley, & Wade, 1991; Miozzo & Caramazza, 1997). Although not systematically documented, alternates can sometimes share both phonological and semantic features with the target (e.g., Brown, 1991; Burke et al., 1991), as with musicians Elton and Elvis whose names also have the same first syllable. Another characteristic of alternates is that when present during a TOT, they reduce the likelihood of retrieving the target, relative to TOTs that are not accompanied by alternates (Burke et al., 1991). The present research explored a possible link between the target and alternate's sharing phonological and semantic features and a subsequent reduction in target retrieval (i.e., TOT resolution). Although TOTs are often described as lapses in efficient word retrieval, they are also particularly useful tools for investigating the processes that underlie speech production. Theories of speech production generally agree that word retrieval requires selecting a lemma (i.e., a lexical representation that is semantically and syntactically specified) from all lemmas stored in one's mental lexicon, followed by phonological encoding of that lemma (e.g., Dell, 1986; Levelt, 1989). TOTs are thought to result from a breakdown between the two processes, lexical selection Proper Name Retrieval 4 and phonological encoding, such that lexical selection was completed successfully but phonological encoding was not. Why would lexical selection, but not phonological encoding, be successful? Multiple connections link semantic representations to corresponding lemmas, and activation from these converging connections allows selection of the lemma to occur relatively easily. In contrast, single connections link lemmas to each of their phonological nodes. Whereas connections to any node can become weak if not used frequently or recently, nodes with single connections are particularly susceptible to deficits in the transmission of activation because they do not benefit from a convergence of activation from multiple sources. Thus, TOTs result when weakened phonological connections do not receive sufficient top-down activation from their lemma (e.g., James & Burke, 2000; Rastle & Burke, 1996). Although TOTs occur for all types of words (e.g., nouns, adjectives, verbs), proper names are particularly susceptible to retrieval deficits (e.g., Burke et al., 1991; Evrard, 2002; Hanley, 2011). As with all word types, retrieval of a proper name requires lemma selection and phonological encoding. However, within theories of speech production, the dominant theoretical explanation of increased TOTs for proper names (see Figure 1) proposes an additional singlesource connection that must be traversed before phonological encoding begins (for details see Burke et al., 1991, and Valentine, Brennen, & Brédart, 1996; but see Bredart, 1993, and Hanley, 2011, for other explanations of why there are more TOTs for people's names relative to nonnames). Proper names such as Elton John require activation of the lemmas for each individual name (first and last) via single connections from the proper name phrase. Thus, proper names are especially susceptible to TOTs because retrieving a full name requires activation of both individual names via single connections, and both names must then be phonologically encoded (Burke et al., 1991; Burke, Locantore, Austin, & Chae, 2004; Valentine et al., 1996). Consistent Proper Name Retrieval 5 with this theory, more TOTs occur for three-word names (which have more single-source connections) than two-word names (Hanley & Chapman, 2008). Furthermore, words presented as occupations (e.g., a farmer) are easier to learn and recall than identical words presented as proper names (e.g., Kelly Farmer; James, 2004; McWeeny, Young, Hay, & Ellis, 1987). Whereas the noun farmer and the proper name phrase Kelly Farmer can both benefit from multiple converging connections from their semantic nodes to achieve lexical selection, the additional step of activating the last name lemma Farmer makes its retrieval more difficult than the occupation. Phonological priming Given that TOTs are thought to result from insufficient activation of phonology, previous research has investigated the influence of phonological primes1 (i.e., words that contain some or all aspects of the target's phonology) on TOT incidence and resolution. Phonological primes provide a vehicle by which the weakened lexical-to-phonological connections that cause TOTs can be strengthened, which can prevent TOTs from occurring in the first place (e.g., James & Burke, 2000, Experiment 1). With respect to resolving TOTs, phonological priming studies use a methodology where a TOT is first induced via a general knowledge question. Phonological primes (or unrelated words as a control) are then presented, followed by the original TOTinducing question. TOT resolution (retrieving the intended target) is measured as a function of whether primes or unrelated words were presented. Compared to unrelated words, target retrieval is increased when participants are primed with words that share phonology with the target (James & Burke, 2000, Experiment 2), specifically the first syllable (e.g., Abrams, White, & Eitel, 2003; White & Abrams, 2002). Even though TOTs are most common for proper names, the majority of studies that involve phonological priming have focused on TOTs for non-proper Proper Name Retrieval 6 names (i.e., low-frequency words from other grammatical classes such as nouns and verbs). One exception was a study by Burke et al. (2004), who demonstrated that TOTs were less likely to occur when phonological primes were presented before the target name. Specifically, naming homophone primes (e.g., cherry pit) both reduced TOT states and increased correct retrieval of famous target names whose last names were identical to the homophone's phonology (e.g., Brad Pitt). All of these findings that phonological primes facilitate word retrieval contradict the notion that related words can cause TOTs (i.e., the blocking hypothesis; e.g., Jones, 1989; Jones & Langford, 1987). However, we do know that once in a TOT, alternate words can have a "blocking" effect by delaying access to a to-be-retrieved target (Burke et al., 1991), suggesting that there must be some circumstances that increase the difficulty of retrieving a target. In support of this hypothesis, Abrams and Rodriguez (2005; see also Abrams, Trunk, & Merrill, 2007) demonstrated that a phonological prime only facilitated TOT resolution when the prime and target differed in part of speech. When a phonological prime shared part of speech with a target, the degree of TOT resolution was equivalent to resolution following unrelated words, indicating no priming. Abrams and colleagues interpreted these results in terms of grammatical class creating competition for lexical selection (e.g., Dell, 1986; MacKay, 1987): The most active lemma within a particular grammatical class is selected (in this case, the prime), and its activation level must subside before another word in that grammatical class (the target when it is the same part of speech) can be selected for production. The constraints imposed by grammatical class on TOT resolution are exacerbated because the prime and target also share phonology, making them especially competitive with each other for retrieval. Semantic priming Proper Name Retrieval 7 Unlike the facilitation in target retrieval that results from phonological primes, there appear to be no effects on TOT incidence when participants are primed with solely semantic primes: Cross and Burke (2004) found that producing a character’s name (e.g., Eliza Doolittle) did not increase TOTs when later asked to produce the corresponding actor's name (Audrey Hepburn). Similar evidence has been shown with semantic cues having no influence on TOT incidence for non-names (Meyer & Bock, 1992). Thus, there appears to be little evidence that semantic alternates, when presented implicitly through priming or explicitly through cuing, influence TOTs by blocking their retrieval when no phonological overlap is present. Theoretically, a semantically-related alternate word can impair retrieval of a target if it creates competition at lexical selection, which results in slower selection of the correct target, as shown in picture word interference tasks with semantic distractors (e.g., Schriefers, Meyer, & Levelt, 1990). However, because lexical selection has already been completed when a TOT occurs, semantic priming should not have an effect on the phonological encoding stage and influence TOTs, consistent with the above findings. Interactions between phonology and semantics Although semantic-only primes have had little influence on TOTs in previous research, we tested whether semantic overlap between primes and targets could constrain phonological priming of TOT resolution. In other speech production tasks like picture naming, participants are asked to name a target picture while ignoring a prime2, but the prime can nonetheless influence target naming. For example, semantic overlap between primes and targets has been shown to mediate phonological priming effects on production (e.g., Cutting & Ferreira, 1999; Taylor & Burke, 2002). In these experiments, production of a target is influenced not by the prime per se but by a word related to the prime. For example, Cutting and Ferreira (1999) presented primes Proper Name Retrieval 8 (e.g., prom) that were semantically related to one meaning of a homonym (e.g., ball) and then asked people to name target pictures that represented the other meaning of the homonym (e.g., a picture of a toy ball). Relative to unrelated words, primes facilitated picture naming. However, when there is the potential for competition from a semantically-related word at lexical selection, mediated priming from phonology is no longer facilitatory. Abdel Rahman and Melinger (2008) used Dutch primes (e.g., dokter, mandarijn) that were phonologically related to a nonpresented word that was a semantic competitor (e.g., dolfijn [meaning dolphin]) of the target picture (e.g., haai [meaning shark]), and primes produced slower naming times of targets compared to unrelated words. If semantic competition can eliminate the facilitatory effects of phonological priming on picture naming, then it may have a similar influence on TOT resolution. Testing whether semantic competition constrains phonological priming of TOT resolution would be virtually impossible to assess with low-frequency non-names (e.g., bandanna) that are often used to induce TOTs because of the difficulty in finding primes and targets that are both phonologically and semantically related. However, proper names are ideal primes and targets because they can overlap phonologically (e.g., by sharing either the first or last name) and semantically (e.g., by sharing the same profession). Predictions within theories of speech production This experiment manipulated the semantic relationship between primes and targets as well as the amount of phonology shared by primes and targets. Specifically, primes were from either the same or different profession as the target and either shared partial (i.e., first syllable) or full (i.e., first name) phonology with the target. For example, Elvis and Elton share first-syllable phonology and are from the same profession, whereas Helen Keller and Helen Hunt share first Proper Name Retrieval 9 name phonology and are from a different profession. Two current theories of speech production were used to derive hypotheses about the influences of these variables on TOT resolution. Interactive activation theories postulate a bidirectional spread of activation between lemmas and their phonological representations (e.g., Dell, 1986; MacKay, 1987), whereas discrete theories (e.g., Levelt, 1989; Roelofs, 2004) maintain feedforward-only activation between lemmas and phonological nodes. Whereas both theories predict phonological priming of TOT resolution, they differ in their predictions for whether semantic competition could mediate the effects of phonological priming. With respect to phonological priming of TOT resolution, interactive activation theories (represented in Figure 2) maintain that presentation of a prime (Elmer Fudd) activates its lemma, which sends top-down activation to its phonological representations (e.g., the syllable node /ɛl/). Activation then feeds back from phonology to associated lemmas sharing that phonology (e.g., Elmo, Elliot), one of which is the target (Elton). This phonological feedback increases the target’s chance of being resolved, unlike a phonologically-unrelated word which provides no feedback to the target. Alternatively, discrete theories explain phonological priming by postulating connections between perceptual and production systems, where phonological primes activate related lemmas in the perceptual system, which then facilitates production of the target by activating the target’s phonology in the production system. In the present experiment, we anticipated that both first name and first syllable primes would facilitate TOT resolution in the absence of shared semantic features, consistent with speech production theories and with previous research on non-names (e.g., James & Burke, 2000; Abrams et al., 2003). However, only interactive activation theories predict an interaction of phonological priming with semantic category, where phonological primes sharing semantic category with Proper Name Retrieval 10 targets will compete for retrieval, thus preventing TOT resolution relative to unrelated names (see right side of Figure 2). During the initial attempt to retrieve the target, all lemmas that correspond to the semantically-appropriate concept (e.g., musician) will be partially activated, creating a situation where semantically-related words could compete with the target for retrieval (e.g., Schriefers, Meyer, & Levelt, 1990). Following a TOT, presentation of a semanticallyrelated prime that is also phonologically related (e.g., Elvis Presley) increases its competitiveness because the prime receives both top-down activation from semantics and feedback activation from its phonology. This converging activation to the prime prevents the target (Elton John) from being activated as long as the prime remains active. Unlike interactive activation theories, discrete theories do not recognize feedback as a property of the lexical system and therefore would not predict an interaction between phonological primes and semantic category. If semantic competition can be created from phonological primes, as predicted by interactive activation theories, the degree of phonological overlap may also be relevant to the circumstances under which semantic competition at lexical selection occurs. In contrast to the above-described predictions for partial phonological primes, presenting the target’s entire first name phonology (via the prime) may provide the target with sufficient phonological feedback to activate its lemma, minimizing effects of semantic competition from the prime. Because feedback activation from phonology to lemmas is thought to be relatively weak (Abdel Rahman & Melinger, 2008; Dell & O'Seaghdha, 1991, 1992), additional phonological feedback provided by a full-name prime could be sufficiently strong to enable activation of the target’s lemma regardless of top-down activation that the prime receives from its semantic nodes. Alternatively, having the entire first name could increase competition for retrieval when both the prime and target are in the same semantic category because phonological feedback from all of the first Proper Name Retrieval 11 name's phonemes is also going to the prime's lemma. A prime that only shares partial phonology with a target will not receive as much phonological feedback as a full name prime, thus providing the target a greater chance to reach activation. In sum, primes that share entire first name phonology with the target are expected to provide more feedback activation to lemmas relative to primes that share partial phonology. Whether this increased activation will result in reduced competition (due to the boost in feedback activation to the target's lemmas) or greater competition (due to sustained activation of the prime) was assessed in the present experiment. Method Participants Participants included 136 Rhodes College undergraduates (92 females, 44 males) who reported English as their first language. All participants were between the ages of 18 and 22 years (M = 19.16, SD = 1.19) and received course credit or extra credit for participating. Materials Ninety famous target names were selected from the following professions3: actors, comedians, directors, or models (47%); musicians (16%); TV hosts, authors, or journalists (8%); athletes (9%); politicians or historical figures (8%), and characters (12%). Forty-five target names were assigned two phonological primes that shared complete first-name phonology with the target, and 45 target names were assigned two phonological primes that shared the first syllable with the target's first name.4 Primes differed in their semantic relatedness to the target, defined by each name's profession; one prime was from the same semantic category as the target (e.g., both were actors), whereas the other prime was from a different semantic category. Although each target was assigned a prime that shared or differed in semantic category with the target, and presentation of primes was counterbalanced across participants, we were unable to Proper Name Retrieval 12 fully counterbalance phonological overlap. Finding four prime names (two first-name and two first-syllable primes, one of which shared and one of which differed in the target’s semantic category) was impossible, so different targets were assigned primes that shared full first-name phonology or partial first-syllable phonology. Targets and primes always shared gender and were frequently matched on race (82%). In addition to the two primes assigned to each target, targets were assigned an unrelated name that did not share phonology or semantic category with its corresponding target. Half of the unrelated names matched the same semantic category prime's number of syllables, while the other half matched the different semantic category prime's number of syllables. When presenting a prime, the computer program randomly selected whether the prime was in the same category, different category, or was unrelated, but also ensured that each of these was chosen equally often. Questions were created for target, prime, and unrelated names. Target questions described specific semantic information leading to answers that were the target names. In contrast, questions for the prime and unrelated names embedded the names at the beginning of the questions and asked some relatively easily retrieved fact about those people. Example targets, primes, unrelated names, and questions are shown in Table 1. A recognition test was created for participants to identify target names that they did not retrieve after the second presentation of the target question. The target question was presented along with four answer choices: the target and three other names that shared the same semantic category, age group, and gender as the target. The target was counterbalanced equally often across the four possible answer choice positions (a, b, c, and d), with one additional (a) and one additional (b) choice. A post-experiment questionnaire assessed participants’ awareness of the phonological relationship between targets and primes as well as their intent to strategically use the relationship to resolve TOT states. A Proper Name Retrieval 13 program written in Visual Basic 5.0 was used to present all stimuli and record participants’ responses. Design and Procedure The experimental design was 3 (Prime Condition) x 2 (Target Type) within-subjects design. Prime Condition had three levels: (1) a phonological prime in the same semantic category as the target, (2) a phonological prime in a different semantic category from the target, or (3) a phonologically and semantically unrelated name (see Table 1). Target Type contained two levels: (1) targets whose phonological primes shared first-name phonology, and (2) targets whose phonological primes shared first-syllable phonology. An experimenter provided participants with written and verbal instructions, describing TOT states as the experience when one is temporarily unable to retrieve a well-known word from memory. The computer program presented target questions in random order, and after reading each question participants indicated "known," "unknown," or "TOT." Upon indicating "known", participants provided the answer and were then presented with a new target question. After "unknown" or "TOT" responses, participants were presented with either a prime question (same or different semantic category) or an unrelated question. After answering the prime/unrelated question, the original target question was presented a second time, and retrieval of the target name was reattempted, with participants again indicating whether they knew, did not know, or were still having a TOT. After all 90 target questions were presented, participants completed the recognition test. Finally, the post-experiment questionnaire was administered. Results Initial Responses. Initial "known" and "TOT" responses to target questions were categorized as either correct or incorrect. Known responses were correct if participants produced the target Proper Name Retrieval 14 name. TOT responses were considered correct if the target name was produced on the second presentation of the question or if the correct answer choice was selected on the recognition test (these responses are often referred to as “positive TOTs”, e.g., Brown & McNeill, 1966). Initial responses to targets are shown in Table 2, separately for targets that were subsequently primed with first-name primes vs. first-syllable primes. Despite using different targets in the first-name and first-syllable prime conditions, the overall patterns of responding were generally similar. Target Retrieval following Correct "TOT" Responses. In order to assess the influence of primes that were phonologically and/or semantically related to our intended targets on TOT resolution, only correct TOTs were included in analyses. A 3 (Prime Condition) x 2 (Target Type) repeatedmeasures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed by participants5 on the mean proportion of target retrieval following the second presentation of the target question (see Figure 3). Fortyseven (35%) participants were unable to be included in this analysis because they did not have at least one correct TOT in one of the six conditions. A marginal main effect of target type, F(2, 176) = 2.83, MSE = .11, p = .096, η2 = .03, revealed slightly more TOT resolution for targets assigned to first-name primes (M = 33.5%) than targets assigned to first-syllable primes (M = 28.7%). A significant main effect of prime condition, F(2, 176) = 6.33, MSE = .11, p = .002, η2 = .07, showed priming of TOT resolution such that resolution following phonological primes in a different semantic category (M = 38.0%) was greater than resolution following unrelated names (M = 25.7%), p < .001, η2 = .11, whereas resolution following phonological primes in the same semantic category (M = 29.5%) was equivalent to resolution following unrelated names, p = .284, η2 = .01. These effects were moderated by a significant Prime Condition x Target Type interaction, F(2, 176) = 3.12, MSE = .10, p = .047. For targets assigned to first-name primes, significant priming of TOT resolution occurred following both same- and different-category Proper Name Retrieval 15 phonological primes: relative to unrelated names, more TOT resolution occurred following same-category primes (p = .015, η2 = .07) as well as different-category primes (p = .005, η2 = .09). Similar resolution was found following same- and different-category primes (p = .534, η2 = .004). For targets assigned to first-syllable primes, marginally significant priming of TOT resolution occurred following different-category primes, which led to greater resolution than unrelated names (p = .072, η2 = .04) and same-category primes (p = .004, η2 = .09). However, same-category primes did not show priming, resulting in similar TOT resolution as unrelated names, p = .314, η2 = .01. The post-experiment questionnaire was used to categorize participants as being aware of the priming manipulation and, more importantly, intending to use primes to help retrieval of targets. Sixty-one participants in the above analysis were categorized as aware of the relationship between the primes and targets because they mentioned the phonological relationship between the primes and targets. Despite this awareness, relatively few of these participants (N=25) also demonstrated intent to use the primes as a way to resolve targets. To ensure that strategic retrieval processes were not the cause of the priming results, only the 64 participants categorized as not having intent were included in a 3 (Prime Condition) x 2 (Target Type) ANOVA. Although there was no main effect of target type, F < 1, there was a significant main effect of prime condition, F(2, 126) = 5.45, MSE = .11, p = .005, η2 = .06, and a marginal Prime Condition x Target Type interaction, F(2, 126) = 2.76, MSE = .10, p = .068. Following up this interaction revealed the same pattern of results as the analysis including all participants. Discussion This experiment demonstrated a novel constraint on TOT resolution: Shared semantic category limited the ability of a prime's phonology to increase TOT resolution, but only when the Proper Name Retrieval 16 prime did not fully overlap in phonology with the target’s first name. Furthermore, these effects did not result from participants using strategic processes to elicit the target's retrieval. The lack of priming of TOT resolution when primes and targets shared semantic category and only partial (first syllable) phonology is explained by theories that assume feedback from phonological nodes to associated lemmas (e.g., Dell, 1986; MacKay, 1987). The phonological feedback, coupled with top-down semantic activation to the prime, is sufficient to maintain activation of the prime, which results in delayed target retrieval for as long as the prime remains active (see Figure 2). Although phonological feedback is also sent to the target, feedback from only one syllable is relatively weak, allowing for potential competition from semantically-related words (e.g., Abdel Rahman & Melinger, 2008). This competition suggests that constraints on lemma activation during TOT resolution for names can come from semantics, similar to findings from speech production studies with non-names (e.g., Schriefers et al., 1990). In contrast to first-syllable primes that shared semantic features with the target, when a prime shared entire first name with a target, it facilitated TOT resolution. This finding suggests that sufficient phonological overlap can offset potential semantic competition and provide enough activation to the target’s lemma to boost TOT resolution. In the absence of semantic overlap, both first-name and first-syllable phonological primes increased TOT resolution, consistent with both interactive activation (e.g., Dell, 1986) and discrete (e.g., Levelt, 1989) theories of speech production. These results emphasize the importance of the first syllable in resolving TOTs for proper names, again paralleling findings of priming with non-names (e.g., Abrams et al., 2003; White & Abrams, 2002). However, the priming effect following first-syllable primes was marginal (M = 9.6), compared to a highly significant priming effect (M = 12.1) following first-name primes. While we must interpret these Proper Name Retrieval 17 results cautiously since different target names are being compared, these results suggest the extent of phonological priming may be contingent on the amount of phonological feedback, as first-name primes provide more phonological feedback than first-syllable primes. As illustrated in Figure 2, phonological priming of names that share first syllable would occur when feedback travels from the first syllable /ɛl/ to Elton and then across an additional connection to the proper name phrase Elton John. In order to retrieve the target, bottom-up activation must be sufficient to facilitate activation of the remainder of Elton John’s phonology. However, less priming might be expected from first-syllable primes than from first-name primes due to insufficient bottom-up activation being transmitted from a single syllable. Another explanation for the reduction in phonological priming is that in the present task, two words (both names) must get activated, and the ability of a single syllable to facilitate retrieval of both names may become increasingly more difficult. Demonstrating that semantics and phonology interact to influence TOT resolution offers unique insight into the underlying processes of lexical selection and phonological encoding. TOTs are special cases where production is unsuccessful and indeed is momentarily "frozen" between two stages, lexical selection and phonological encoding. Thus, whereas the picture naming task provides insight into processes that affect (successful) lemma selection, the TOT resolution methodology provides insight into processes that occur at a later stage in production, namely after a lemma has been selected but before it has been successfully phonologically encoded. The role of semantic competition has clearly been demonstrated prior to lexical selection via picture naming (e.g., Schriefers et al., 1990), but the present study has shown that semantics continues to play a role in the later stages of production (i.e., after lexical selection has occurred) by interfacing with phonology to constrain which associated lemmas get activated. The Proper Name Retrieval 18 interactive effect of semantics and phonology on TOT resolution also parallels previous studies using other speech production tasks, such as picture naming (Abdel Rahman & Melinger, 2008; Cutting & Ferreira, 1999; Taylor & Burke, 2002) as well as studies of speech errors for proper names (Brédart & Valentine, 1992; Martin, Weisberg, & Saffran, 1989), which find a greater proportion of mixed phonological and semantic substitutions compared to solely semantic or phonological errors. Although the comparison of names and non-names was not manipulated in the present experiment, using TOT resolution to investigate proper name retrieval may also provide insight into why proper names are particularly difficult to learn and retrieve. One way in which proper names differ from non-names is that the latter are more likely to have synonyms (e.g., movie, film, show) that can be substituted during speech production in order to not disrupt the flow of speech (Cohen & Faulkner, 1986). Evidence supporting this view was recently shown by Hanley (2011), who found no differences in proper and common name retrieval when controlling for the number of alternative words or names that could be used in place of a target. Further, Brédart (1993) found more correct naming of faces that had two names (a real name and a character name) associated with them than faces that had one name associated with them. Another potential source for the increased difficulty in retrieving proper names is the frequency with which the name is encountered (e.g., Hanley & Chapman, 2008), supported by evidence that more common names (e.g., Davis) are easier to learn and recall than less common names (e.g., Davin; James & Fogler, 2007). The results of the present study offer additional conditions that influence why proper names are oftentimes more difficult to retrieve than non-names: Proper names may be more likely to have semantic competition along with phonological overlap, conditions that impeded TOT resolution in our study. Although some non-names are Proper Name Retrieval 19 semantically- and phonologically-related (e.g., chastity and charity), they are certainly more rare than proper names that can share semantic features such as profession. Our data also offer behavioral evidence consistent with recent claims that proper and common names are represented differently at the neural level (Semenza, 2006, 2009). The present experiment found phonological priming between names without semantic overlap, suggesting that proper names are not competitive with each other, independent of other shared features. In contrast to proper names, phonologically-similar non-names are quite competitive, as illustrated by a lack of phonological priming when primes and targets share grammatical class (Abrams & Rodriguez, 2005; Abrams et al., 2007). Thus, proper names seem to function differently from non-names in terms of the role that grammatical class plays in their production. In conclusion, the present results suggest one potential reason for why alternates might delay TOT resolution in everyday life: Alternates can share both phonology and semantic features with targets, causing them to compete for retrieval. It is worth noting that inhibitory effects on TOT resolution were not observed in the present experiment (i.e., where TOT resolution following unrelated names was greater than same-category primes). However, it is possible that inhibitory effects from shared semantic category would be easier to detect in old age (see Abrams et al., 2007), given that TOTs increase with age (Burke et al., 1991), especially for proper names (e.g., Evrard, 2002; Rendell, Castel, & Craik, 2005). Older adults' enhanced semantic networks, combined with age-related deficits in the transmission of phonological activation, could potentially make them more susceptible to competition from phonologicallyand semantically-related alternate names and result in a reduction in TOT resolution. More generally, continued investigations of the circumstances under which TOT resolution for proper names is either facilitated or inhibited will lead to a better understanding of the interactions Proper Name Retrieval 20 between lexical selection and phonological encoding. These stages of word retrieval are critical for distinguishing between discrete and interactive activation theories of speech production and will give further insight into why names are particularly vulnerable to retrieval deficits. Proper Name Retrieval 21 References Abdel Rahman, R., & Melinger, A. (2008). Enhanced phonological facilitation and traces of concurrent word form activation in speech production: An object-naming study with multiple distractors. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61, 1410–1440. doi: 10.1080/17470210701560724. Abrams, L., & Rodriguez, E. L. (2005). Syntactic class influences phonological priming of tipof-the-tongue resolution. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 12, 1018–1023. Abrams, L., Trunk, D. L., & Merrill, L. A. (2007). Why a superman cannot help a tsunami: Activation of grammatical class influences resolution of young and older adults’ tip-ofthe-tongue states. Psychology and Aging, 22, 835–845. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.4.835 Abrams, L., White, K. K., & Eitel, S. L. (2003). Isolating phonological components that increase tip-of-the-tongue resolution. Memory and Cognition, 31, 1153–1162. Baayen, R. H., Tweedie, F. J., & Schreuder, R. (2002). The subjects as a simple random effect fallacy: Subject variability and morphological family effects in the mental lexicon. Brain and Language, 81, 55–65. doi: 10.1006/brln.2001.2506 Brédart, S., & Valentine, T. (1992). From Monroe to Moreau: An analysis of face naming errors. Cognition, 45, 187–223. Brown, A. S. (1991). A review of the tip-of-the-tongue experience. Psychological Bulletin, 109, 204–223. Brown, R. & McNeill, D. (1966). The "tip of tongue" phenomenon. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 5, 325–337. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(66)80040-3 Proper Name Retrieval 22 Burke, D. M., Locantore, J. K., Austin, A. A., & Chae, B. (2004). Cherry pit primes Brad Pitt: Homophone priming effects on young and older adults' production of proper names. Psychological Science, 15, 164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.01503004. Burke, D. M., MacKay, D. G., Worthley, J. S. & Wade, E. (1991). On the tip of the tongue: What causes word finding failures in young and older adults? Journal of Memory and Language, 30, 542–579. doi:10.1016/0749-596X(91)90026-G Burton, A.M. & Bruce, V. (1992). I recognise your face, but I can't remember your name: a simple explanation? British Journal of Psychology, 83, 45–60. Clark, H. H. (1973). The language-as-fixed-effect fallacy: A critique of language statistics in psychological research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12, 335–359. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(73)80014-3 Cohen, G., & Faulkner, D. (1986). Memory for proper names: Age differences in retrieval. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 4, 187–197. Cutting, J. C., & Ferreira, V. S. (1999). Semantic and phonological information flow in the production lexicon. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 25, 318–344. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.25.2.318 Dell, G. S. (1986). A spreading-activation theory of retrieval in sentence production. Psychological Review, 93, 283–321. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.93.3.283 Dell, G. S., & O’Seaghdha, P. G. (1991). Mediated and convergent lexical priming in language production: A comment on Levelt et al. (1991). Psychological Review, 98, 604–614. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.4.604 Dell, G. S. & O'Seaghdha, P. G. (1992). Stages of lexical access in language production. Cognition, 42, 287–314. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(92)90046-K Proper Name Retrieval 23 Evrard, M. (2002). Ageing and lexical access to common and proper names in picture naming. Brain and Language, 81, 174–179. doi: 10.1006/brln.2001.2515 Hanley, J. R. (2011). Why are names of people associated with so many phonological retrieval failures? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18, 612–617. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-00820 Hanley, J. R., & Chapman, E. (2008). Partial knowledge in a tip-of-the-tongue state about twoand three-word proper names. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 15, 156- 160. doi: 10.3758/PBR.15.1.156 James, L. E. (2004). Meeting Mr. Farmer versus meeting a farmer: Specific effects of aging on learning proper names. Psychology and Aging, 19, 515-522. doi: 10.1037/08827974.19.3.515 James, L. E. & Burke, D. M. (2000). Phonological priming effects on word retrieval and tip-ofthe-tongue experiences in young and older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Memory, Learning, and Cognition, 26, 1378–1391. doi:10.1037//0278-7393.26.6.1378 James, L. E., & Fogler, K. A. (2007). Meeting Mr. Davis versus Mr. Davin: Effects of name frequency on learning proper names in young and older adults. Memory, 15, 366-374. doi:10.1080/09658210701307077 Jones, G. V. (1989). Back to Woodworth: Role of interlopers in the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. Memory and Cognition, 17, 69-76. Jones, G.V., & Langford, S. L. (1987). Phonological blocking in the tip of the tongue state. Cognition, 26, 115-122. Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Proper Name Retrieval 24 MacKay, D. G. (1987). The organization of perception and action: A theory for language and other cognitive skills. New York: Springer-Verlag McWeeny, K. H., Young, A. W., Hay, D. C., & Ellis, A. W. (1987). Putting names to faces. British Journal of Psychology, 78, 143–149. Miozzo, M. & Caramazza, A. (1997). Retrieval of lexical-syntactic features in tip-of-the tongue states. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 23, 1410–1423. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.23.6.1410 Raaijmakers, J. G. W., Schrijnemakers, J. M. C., & Gremmen, F. (1999). How to deal with "The language-as-fixed-effect fallacy"; Common misconceptions and alternative solutions. Journal of Memory and Language, 41, 416–426. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1999.2650 Rastle, K. G., & Burke, D. M. (1996). Priming the tip of the tongue: Effects of prior processing on word retrieval in young and older adults. Journal of Memory and Language, 35, 585– 605. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1996.0031 Rendell, P. G., Castel, A. D., & Craik, F. I. M. (2005). Memory for proper names in old age: A disproportional impairment? The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58A, 54–71. doi:10.1080/02724980443000188 Roelofs, A. (2004). Error biases in spoken word planning and monitoring by aphasic and nonaphasic speakers: Comment on Rapp and Goldrick (2000). Psychological Review, 111, 561–572. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.561 Schriefers, H., Meyer, A. S., & Levelt, W. J. (1990). Exploring the time course of lexical access in language production: Picture-word interference studies. Journal of Memory and Language, 29, 86–102. doi: 10.1016/0749-596X(90)90011-N Proper Name Retrieval 25 Semenza, C. (2006). Retrieval pathways for common and proper names. Cortex, 42, 884–91. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70432-5 Semenza, C. (2009). The neuropsychology of proper names. Mind & Language, 24, 347-469. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0017.2009.01366.x Taylor, J. K., & Burke, D. M. (2002). Asymmetric aging effects on semantic and phonological processes: Naming in the picture-word interference task. Psychology and Aging, 17, 662– 676. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.662 Valentine, T., Brennen, T., & Brédart, S. (1996). The cognitive psychology of proper names: On the importance of being Ernest. London: Routledge. Vitkovitch, M., Potton, A., Bakogianni, C., & Kinch, L. (2006). Will Julia Roberts harm Nicole Kidman? Semantic priming effects during face naming. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59, 1134-1152. doi:10.1080/02724980543000178 White, K. K., & Abrams, L. (2002). Does priming specific syllables during tip-of-the-tongue states facilitate word retrieval in older adults? Psychology and Aging, 17, 226–235. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.17.2.226 Proper Name Retrieval 26 Footnotes 1 Using primes to strengthen connections to phonology provides an understanding of TOT resolution independent of strategic processing, which occurs in cueing paradigms where one can use a given word to help trigger recall of the target. Although there is a substantial literature on TOT incidence and resolution when strategic retrieval processes are engaged via presentation of cues (e.g., Brennen, Baguley, Bright, & Bruce, 1990; Freedman & Landauer, 1966; Heine, Ober, & Shenaut, 1999; Jones, 1989; Meyer & Bock, 1992; Perfect & Hanley, 1992), we do not discuss that literature because priming effects are thought to better resemble normal word retrieval (Meyer & Bock, 1992) and the spontaneous TOT resolution that occurs when phonology is encountered “inadvertently in conversation” (James & Burke, 2000, p. 1379). 2 Picture naming studies typically refer to these primes as "distractors" because they are intended to be ignored while participants name pictures. However, for consistency and because phonology typically facilitates naming in TOT resolution, we use the term "primes". 3 There were two exceptions to the "professions" categorization: historical figures and characters. Proper names were categorized as historical figures if they had a significant impact on United States or world history (e.g., Alexander Hamilton, John Locke) and as characters if they were fictional figures portrayed in movies, television shows, or books (e.g., Peter Parker, Charlie Bucket). 4 Twenty primes (22%) shared phonology beyond just first syllable with the target (e.g., an additional phoneme), and these primes were divided almost equivalently across same and different semantic category conditions. Analysis excluding these primes revealed the same pattern of results as the analysis including all primes. Proper Name Retrieval 5 27 Consistent with most studies of TOT resolution, we did not conduct item analyses for several reasons. TOT rates are typically very low and it cannot be anticipated prior to the experiment on which items participants will have a TOT, which violates underlying statistical assumptions (e.g., Baayen, Tweedie, & Schreuder, 2002; Clark, 1973; Raaijmakers, Schrijnemakers, & Gremmen, 1999). As a result, participants have TOTs on different items, and it is impossible to systematically select the priming condition for an item, which results in many items being excluded from analysis, and thus item analyses are less powerful to detect priming effects. In any case, because participants have TOTs on a different subset of items, the variability across participants in the participant analyses includes item variability to some extent. Proper Name Retrieval 28 Table 1. Example questions, target names, prime names, and unrelated names. Target Question Target Name Phonological Prime in Same Semantic Category Helen Mirren (actor) Phonological Prime in Different Semantic Category Helen Keller (historical figure) Unrelated Name Example Prime/Unrelated Question What is the name of the 47 year old blonde female actor who starred in the movies As Good As It Gets, Twister, Cast Away, What Women Want, and Pay It Forward? Helen Hunt (actor) What is the name of the retired football quarterback who graduated from Notre Dame, won four Super Bowls with the San Francisco 49ers between 1979 and 1994, and currently endorses Sketchers Shape Ups? Joe Namath (athlete) Joe Montana (athlete) Joe Biden (politician) Heath Ledger (actor) Joe Biden, the current Vice President of the United States, was previously the senator for what U.S. state? Delaware Alfred Hitchcock (director) Alec Baldwin (director/ actor) Albert Einstein (historical figure) Herman Melville (author) Herman Melville is the American author who wrote the classic book 'Moby Dick', which is about what type of marine mammal? Whale Elton John (musician) Elvis Presley (musician) Elmer Fudd (character) Chevy Chase (actor) Elvis Presley, the iconic musician who sang the songs 'Jailhouse Rock,' and 'Hound Dog,' owned a mansion in Memphis, TN that is called what? Graceland What is the name of the man who directed the old Hollywood movies 'Psycho,' 'To Catch a Thief,' 'Rear Window,' and 'The Birds'? What is the name of the flamboyant English musician who sings the songs, 'Tiny Dancer,' 'Bennie and the Jets,' and 'Candle in the Wind'? Martha Stewart (business woman) Helen Mirren, the 65 year old British female actor, won an Academy Award for her leading role in what 2006 movie? Answer to Prime Question The Queen Proper Name Retrieval Note: Primes in the first-syllable phonology condition have shared phonology underlined. 29 Proper Name Retrieval 30 Table 2. Percent (%) of initial responses to targets in first-name and first-syllable conditions. _____________________________________________ First-Name First-Syllable Targets Targets _____________________________________________ Correct “Know” 26.9 29.0 Incorrect “Know” 6.4 4.6 Correct “TOT” 16.6 12.2 Incorrect “TOT” 2.4 1.7 Unknown 47.7 52.4 _____________________________________________ Note. Means are based on the 89 participants who were included in the TOT resolution analysis. Proper Name Retrieval reddishmusician British hair Sings “Candle in the Wind” 31 SEMANTIC SYSTEM Propositional Nodes ELTON JOHN Lexical Nodes (lemma) (proper name phrase) ELTON JOHN (initial name) (last name) PHONOLOGICAL SYSTEM /tn/ /ɛl/ /dʒɒn/ Syllable Nodes Phonological Nodes /ɛ/ /l/ /t/ /n/ /dʒ/ /ɒ/ /n/ Figure 1. An illustration of semantic, lexical, and phonological nodes for the proper name Elton John. Weakened single connections between nodes (e.g., the proper name phrase Elton John and the initial name Elton and last name John) are represented by dotted lines. Proper Name Retrieval 32 SEMANTIC SYSTEM musician cartoon character musician ELTON JOHN ELMER FUDD ELTON JOHN ELVIS PRESLEY (proper name phrase) (proper name phrase) (proper name phrase) (proper name phrase) ELTON ELMER ELTON Propositional Nodes Lexical Nodes (lemma) ELVIS PHONOLOGICAL SYSTEM /ɛl/ /tn/ /mər/ /ɛl/ /tn/ /vɪs/ Syllable Nodes Figure 2. A simplified illustration of how phonological primes Elmer Fudd and Elvis Presley affect TOT resolution of Elton John. The left side of the figure illustrates predictions within interactive activation theories regarding TOT resolution following presentation of a phonological prime from a semantic category that is different from the target. The right side of the figure illustrates predictions when presented with a phonological prime from the same semantic category as the target. Although phonological feedback is simplified to illustrate first syllable, note that all aspects of phonology (e.g., last syllable) provide feedback. Proper Name Retrieval Same Semantic Category 50 Different Semantic Category 45 Unrelated Name 40 % TOT Resolution 33 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 First Name Prime First Syllable Prime Target Type Figure 3. Percent target retrieval (TOT resolution) as a function of prime condition (phonological prime in the same semantic category as the target, phonological prime in a different semantic category, unrelated name) and target type (targets whose phonological primes shared first-name phonology, targets whose phonological primes shared first-syllable phonology).