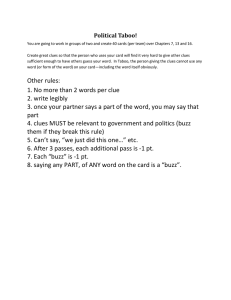

“I DON’T WANNA TALK ABOUT IT”: REINTRODUCING TABOO TOPICS IN

advertisement