THE METABOLISM OF THE INDUSTRIAL CITY The Case of Pittsburgh

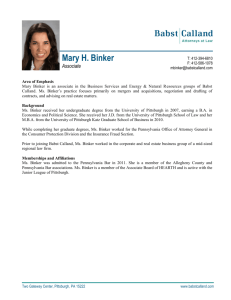

advertisement